Executive Summary: The restrictiveness of monetary policy has been a persistent topic in Fedspeak during this cycle. Nowadays, it is almost guaranteed that whenever they make a public appearance, FOMC members will make some mention of their beliefs as to how restrictive policy is, whether that level is sufficiently restrictive, and uncertainty around the level of restrictiveness. In this piece, we take a deeper dive into the finer details of the national accounts to gain some insight into how exactly monetary policy is restricting investment.

The case that the current level of rates is slowing investment growth is apparent in the recent trends in real investment activity. If the primary effect of high interest rates is to constrain investment, then the effect of restrictive monetary policy on bringing down core PCE inflation is tenuous, and comes with the cost of constraining much-needed investment that may be crucial to expanding supply in the long-run.

Introduction

The Federal Reserve has held rates at their current level for nearly a year. The majority of the committee appears confident that monetary policy is currently restrictive, and from the perspective of that confidence the question for monetary policy is how long rates will need to sit at this level of restrictiveness. Recent statements bear this out.

“I believe that our policy rate is in restrictive territory

Phillip Jefferson, 5/20/24

"I think our stance is restrictive."

Raphael Bostic 5/20/24

"I see the current context as what I would say is moderately restrictive."

Susan Collins 5/21/24

However, a few members on the more hawkish side of the Committee are less convinced that monetary policy is in fact restrictive:

"There are also important upside risks to inflation that are on my mind, and I think there's also uncertainties about how restrictive policy is and whether it's sufficiently restrictive to keep us on this path."

Lorie Logan 5/10/24

“Maybe this constellation is neutral…. So why do anything?”

Neel Kashkari 3/6/24

Looking at the economy from a bird’s eye view, it’s easy to see where the temptation to speculate that current policy is not restrictive is coming from. Despite the Fed holding rates at their highest level in over twenty years, the US economy remains strong: overall growth is robust and consumption is strong while the unemployment rate remains near historic lows. Kashkari succinctly made the case that monetary policy may not be that restrictive, saying: “I’m looking at real economic activity…. real economic activity in the US looks quite robust.”

Yet this points to a deeper problem with the question under consideration. Asking, “Are interest rates restrictive?” oversimplifies the effects of monetary policy on the economy. The question isn’t one-dimensional—changes to monetary policy have different effects on different parts of the economy. Not all sectors are equally sensitive to interest rates, and different sectors are sensitive in different ways. This much is clear in the marked divergence in the paths of investment and consumption ever since the Fed’s hiking cycle began.

As FOMC members are finding out, it’s difficult to gauge just how monetary policy is constraining activity. There are substantial cross-currents in the lingering (but diminishing) effects of pandemic-era fiscal supports, industrial policy, whiplash effects from reopening, and supply chain improvements. However, the details of where real investment has slowed in recent quarters indicate that monetary policy is currently restricting certain areas of investment.

In this piece, we’ll explore the recent developments in real investment activity, where the impact of monetary policy is most apparent. We’ll visit each of the four major categories of investment (residential housing, non-residential structures, equipment, and intangibles) as well as the deeper details of those categories and see where changes in real activity may reflect the restrictive nature of monetary policy.

Housing Looks Restricted, Especially in Multifamily Permits

Are rate hikes constraining the housing sector? On one hand, Kashkari argues that the housing sector has remained resilient to interest rate hikes. Yet the housing sector is traditionally one of the most interest rate sensitive sectors in the economy. Housing inflation is also the largest contributor to ongoing inflation: our current corecast shows rental housing accounting for nearly two-thirds of the excess inflation in core PCE. For months, Austan Goolsbee has referred to the trajectory of housing inflation as the main determinant of the overall inflation picture. As Chair Powell and many other FOMC members have pointed out, the sharp increase in rental inflation can be traced back to decades of underinvestment in housing supply, which was in turn compounded by a surge in housing demand growth as labor income recovered rapidly amidst changing work-from-home patterns.

How much the Fed is restricting the housing sector depends a lot on which measure you look at. Home prices have been rising over the past year, suggesting less restrictiveness on the demand side. But if you look at fixed investment in residential structures on the supply side, the level of investment has been substantially restricted relative to their pre-rate-hike trajectory.

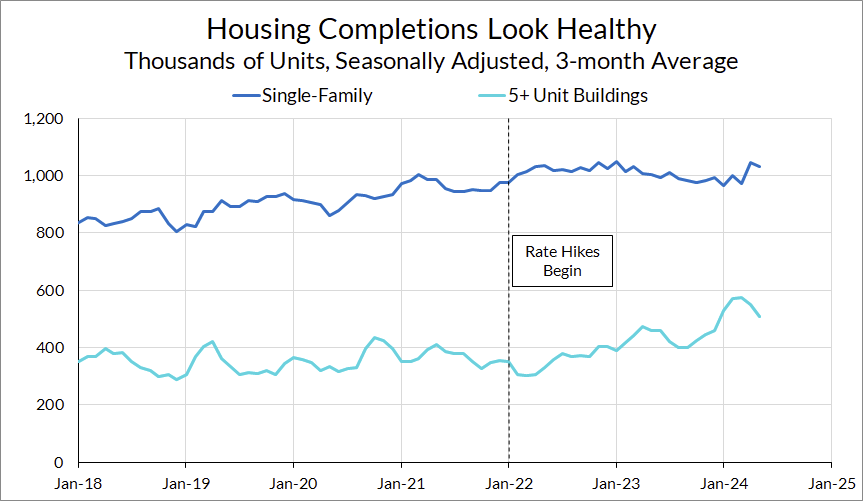

The supply-side news hasn’t been all bad though. Housing completions have also been relatively stable, with a surge of multifamily units coming on board in recent months. This favorable “supply-side” development is poised to lower rent and OER inflation readings in the coming quarters.

But does this mean that Fed policy isn’t that restrictive when it comes to housing? Not necessarily. The completion data may simply reflect the large backlog of housing production that accumulated during the immediate aftermath of the pandemic.

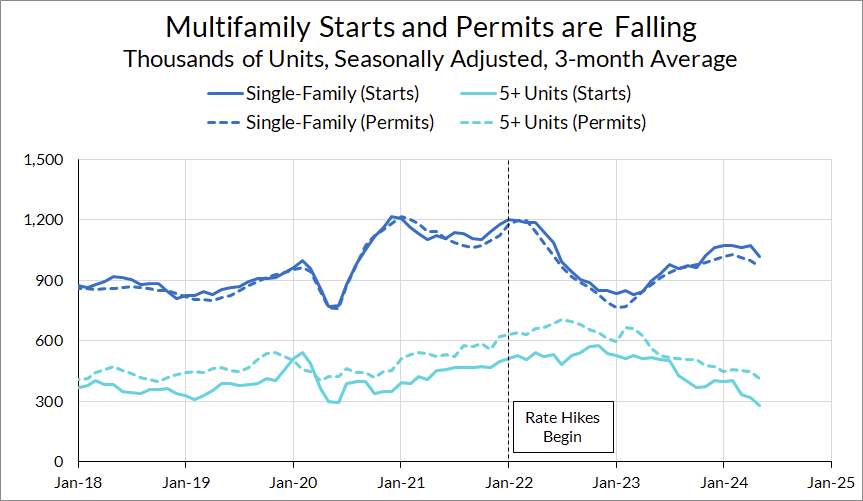

If we look at the housing permits and start data, the power of rate hikes to throttle investment becomes clearer. Housing starts and permits took a huge step back after rate hikes. While single-family starts and permits have rebounded in recent months, multi-family starts and permits are back down to pre-pandemic levels—exactly the level of underbuilding that led to the rental inflation crisis we face today.

So what are the Fed’s high interest rates really accomplishing in the housing sector? The results are ambiguous. Higher rates probably, on the margin, reduce demand for housing and rental prices right now. But as Conor Sen argues, the high rates are going to keep housing construction lower. This could come back to bite the Fed in the future.

Residential construction continues to struggle, with high mortgage rates on the for-sale side. Higher interest rates are driving up the cost of capital and making ‘build to rent’ projects harder to pencil.

Respondent, May 2024 Services ISM Report On Business

When asked about this problem, Tom Barkin acknowledged the longer-term effect on housing supply but maintained the need to reduce inflation in the near-term. The Fed seems to be operating under the theory that high rates will bring inflation down quickly enough that they will be able to reduce rates before further damage is done to housing supply.

This seems like an awfully precise maneuver to pull off using only the blunt tools available to the Fed. Unlike the demand-side effects on rented housing, which are not particularly obvious, the supply-inhibiting effects of rate hikes on rented housing are more readily identifiable.

Non-residential Structures are Booming, but Only Thanks to Manufacturing

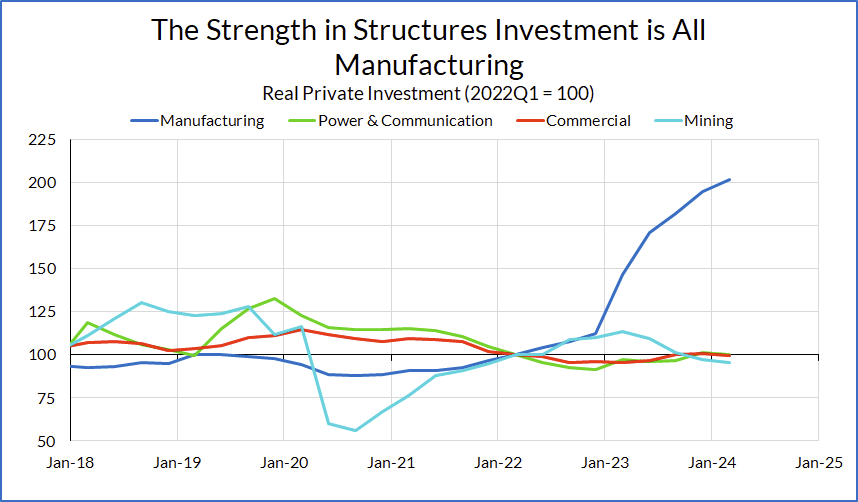

Investment in non-residential structures doesn’t seem to be held back by monetary policy at all, but looks can be deceiving. While the level of investment here is still below the pre-pandemic trend, the growth rate has picked up rapidly in recent quarters. Real investment in this category grew at a healthy clip of 14% over the last four quarters versus the previous four quarters, and contributed 2.1 percentage points to private fixed investment alone in 2023.

However, that underlying strength can be traced back to a single source. Looking into the details of nonresidential structures, the growth in this category is almost single-handedly driven by manufacturing structures. Investment in manufacturing structures was supercharged by fiscal supports (CHIPS, IRA) in 2023, leading to an explosion in growth in this sector. Manufacturing structures investment is now comfortably above-trend, in both its level and growth rate.

Outside of manufacturing structures, growth in nonresidential structures investment is much less impressive. Real activity in most of the subcategories of nonresidential structures investment cratered during the pandemic and is now recovering from that deep recession as supply chains recovered in 2023.

The cross-currents of supply chain healing and fiscal support affecting nonresidential structures make it difficult to precisely state the restrictiveness of monetary policy in this sector. If there’s one area where we can see monetary policy restriction, it’s in the subcategory of “Alternative electric” structures, which comprises wind, solar, dry-waste, and geothermal structures. This sector faces uniquely high up-front costs and is therefore particularly rate-sensitive. While investment in this subcategory grew by 12%, this is still lower than the pre-pandemic growth rate.

We can’t simply infer that monetary policy is not restrictive based on the recent strong growth in structures. Outside of manufacturing, real investment in structures is generally below the levels implied by pre-pandemic trends, despite the recent local pick-up in growth as a result of supply chain healing.

Investment in Business Equipment has Stalled

The slowing in real activity is more apparent in business equipment investment. After recovering to pre-pandemic levels in 2022, real investment in equipment has essentially flatlined since.

This weakness is shared broadly across the subcategories of equipment investment. Growth in real investment in nearly all components of information processing equipment and industrial equipment has been negative recently, and both growth rates and levels are below their pre-pandemic trends.

There are few areas where investment in equipment is growing (the big exception being aircraft manufacturing, which is a lumpy category and probably more related to post-pandemic dynamics and the partial resolution of Boeing’s production issues). Components like special industry equipment (which includes semiconductor manufacturing equipment) and electrical equipment show some green shoots, likely due to boosts from fiscal policy. Outside of those components, there does appear to be a broad slowdown in real equipment investment.

Intangibles Investment Has Slowed, Posing Risks to Future Productivity Growth

Things don’t look much better in our final investment component, as growth in intangible investments has tumbled since monetary policy tightened. Real investment in the three major components of intangibles (research and development, software, and artistic originals) are all growing slower than they were a few years ago.

As with the other categories of investment, there are likely some cross-currents acting on investment in intangibles. For example, rate hikes coincided with the end of full expensing of research and development expenditures. However, there are still good reasons to believe that rate hikes did play an important role in reducing growth research and development investment.

Last August, research presented at the Jackson Hole conference demonstrated that tight monetary policy reduces investment in research and development, which in turn reduces productivity growth for years to come. This paper turned out to be prescient, as measures of innovation activity have declined greatly as the Fed raised interest rates. Growth in private research and development plummeted throughout 2022 and 2023, even contracting briefly in late-2023.

The impact on innovation spending can also be seen in changes in venture capital funding, which has been shown to be particularly important for patent generation (one measure of innovation output).

If rates continue to stay higher for longer, this drag on innovation investment will more acutely alter the trajectory of productivity. As Austan Goolsbee says, productivity could be the “wild card” in the broader path of the economy over the next few years. Higher productivity growth could form the basis for stronger wage and GDP growth and the expanded supply effects of higher productivity would help the Fed meet its inflation mandate in future years. By keeping monetary policy tight—thereby styming investment in productivity growth—the Fed may be making its job harder in the future.

Further Restriction Could be Counterproductive

While rate hikes might be constraining personal consumption at the margin, the case that the current level of rates is slowing investment growth is much more apparent in the data. This highlights some issues with the strategy of using interest rate policy to control consumer price inflation.

The first is that if the primary effect of high interest rates is to constrain investment, that’s much less likely to directly affect core PCE inflation than if rate hikes were effective at directly constraining consumption. The inputs to the production of investment goods do not overlap perfectly with the inputs to production for consumption. While rate hikes do work to reduce consumer prices, the process by which they do so is indirect and mediated by a maze of causal mechanisms

The second is that high rates are constraining much-needed investment that may be crucial to expanding supply in the long-run. The longer-run effects of reducing investment now are likely to pose problems for the Fed in the future, either by increasing inflationary pressures (for example, by reducing housing supply) or reducing productivity growth (by reducing investment in innovation). All else equal, it is a reason to normalize rates earlier rather than later.