This is the second of a two-part series. In the first piece, we took stock of the changing trajectory of the Fed’s 2023 policy goals. While policymakers were never fully convinced of the arguments in favor of a hard landing, they still saw a recessionary increase in unemployment as a requirement for disinflation at the beginning of this year. In the months since, the Fed has backed away from this view, and has expressed increasing confidence in the possibility of a soft landing. In this piece, we look forward to the Fed’s game plan in 2024 as longtime advocates for supply-side disinflation and a soft landing for the labor market. Now that the Fed shares these goals, what risks lay ahead and what steps must they take to preserve the hard-earned recovery in the labor market? We present a path for the Fed in 2024.

Executive Summary

With one FOMC meeting left in 2023, the Fed is expected to end its rate hiking cycle. Although the natural next question is how soon and how quickly the Fed will cut rates, officials have been reluctant to talk about the plan for rate cuts in 2024. "I'm not thinking about rate cuts at all right now”, Mary Daly said in November. Neel Kashkari is also mum on the topic, saying “there’s no discussion amongst me and any of my colleagues about when we’re going to start preparing to cut rates.” Earlier this month, Powell said “it would be premature to conclude with confidence” that rates are sufficiently high to bring inflation down, and even went so far as to say that further rate hikes are not off the table.

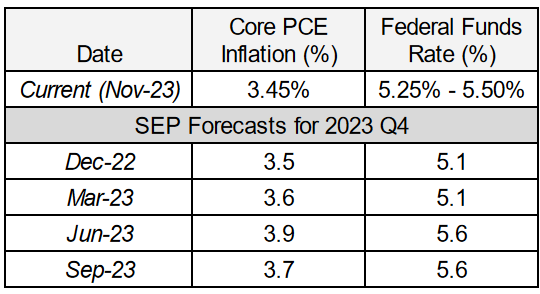

However, it is hard to see the Fed continuing to hike barring serious deterioration in the inflation outlook. With 12-month core PCE inflation already under 3.5%, the inflation trajectory looks much softer than the Fed’s projections from earlier this year. The few Fed officials who have addressed the question about rate cuts, such as Williams, Bostic, and Waller, have all emphasized that the inflation trajectory will guide the timing and pace of any rate cuts in 2024.

Despite Fed officials’ reticence to address the question, we think it’s time to start game-planning the soft landing. The Fed’s position looks to be the inverse of the 2010s. Inflation and interest rates are normalizing to 2% from above, rather than below. The labor market recovery has been strong, rather than anemic, like the post-GFC recovery. Put plainly, the challenge in 2024 is: stave off any recession risks that might threaten either the economy’s current path of supply-driven disinflation or the hard-earned post-pandemic labor market recovery.

In this piece, we will lay out three main policy motivations for interest rate normalization and analyze the strategic implications of each for a successful 2024 soft landing. From the outset, we would like to emphasize the distinction between two different justifications for rate cuts in 2024:

- policy easing to reverse realized deterioration in labor or financial markets, and

- interest rate normalization that would transpire even in the absence of visible financial or labor market deterioration.

This piece primarily focuses on the latter, as the strength of the case for larger and faster interest rate reductions when labor and financial markets are showing distress is already well-understood.

Policy Motivations

- Think preemptively about nonlinear financial stability and unemployment risks. The labor market is still robust, but that can change quickly. When unemployment rises, it usually rises rapidly. Events that threaten financial stability—like the case of Silicon Valley Bank earlier this year—can happen before the Fed is aware. From a risk management perspective, achieving a soft landing requires preempting these events.

- Be Consistent on Inflation. The Fed’s strategy of raising the rate path in response to upside inflation surprises was legible to market participants. Now, the Fed finds itself in the opposite position, as inflation has come in much softer than expected. To maintain legibility and credibility, the Fed should use soft inflation surprises as an opportunity to renormalize interest rates from above.

- The Supply Side Matters. The Fed tends to present supply-side dynamics as though they are upstream from monetary policy, but a mounting body of evidence shows that tight monetary policy constrains the supply side. One lesson of the most recent inflationary episode is that capacity constraints represent a real inflationary threat. As monetary policy works to combat inflation in 2024 by constraining investment, the Fed needs to consider the effect this policy may have on inflation in the long-run.

Strategic Implications

- Risk Management → Front-load rate cuts. The longer interest rates stay high, the longer the economy faces elevated financial stability and unemployment risks. These nonlinear risks dissipate as interest rate normalization advances. The pace of interest rate normalization should therefore begin swiftly but slow as the normalization process advances. The most justified time to pursue a larger 50 basis point “normalization cut” is at the outset.

- Inflation consistency → Lag if you must, but follow inflation down. Just as Fed policy followed inflation on the way up, it should follow inflation on the way down, even if it ultimately transpires with a lag. Normalized labor market outcomes and normalized inflation outcomes warrant normalized interest rate outcomes. Even traditionally hawkish models for monetary policy would make this recommendation: if core PCE were to return to target over the next 4-5 quarters (a 150 basis points reduction), a Taylor-like rule with a coefficient of 1.5 on inflation would call for a cumulative 225 basis points reduction in interest rates (an average of roughly one 25 basis point cut per meeting in 2024).

- Dynamic supply-side forces → Maintain optionality and stay data-dependent. The dynamic effects of Fed policy on investment and future supply—and thereby future inflation—are highly uncertain. While the Fed may not care about the level of investment and growth on the supply-side for their own sakes, it should be very attentive to the dynamic effects of present monetary policy on inflation dynamics beyond 2024. We won’t know how supply will respond to normalization until it happens, so the Fed should maintain flexibility to respond in a data-dependent way by not unduly predetermining the ultimate scale of normalization cuts.

Each of these motivations and implications will be discussed pair-wise in three sections below.

Risk Management, Unemployment, and Financial Stability

Policy Motivation: Think Preemptively About Nonlinear Financial Stability and Unemployment Risks.

The Fed has signaled that they think they can bring down inflation without a recessionary rise in unemployment. The clearest statement of this comes from the latest Summary of Economic Projections (SEP), where the unemployment projection for the end of 2024 has been revised down to 4.1% (from 4.5% in June and 4.6% in March).

The unemployment rate—currently 3.7%, up from this year’s historic low of 3.4%—came close to that projection in October's 3.9% reading. Prime-age employment appears to be plateauing in recent months. Quit and hire rates are essentially at pre-pandemic levels. As we’ve been documenting for the last few months, there has been a considerable slowdown in the labor market, and it’s not clear if there is more to give on the labor market before it starts backsliding.

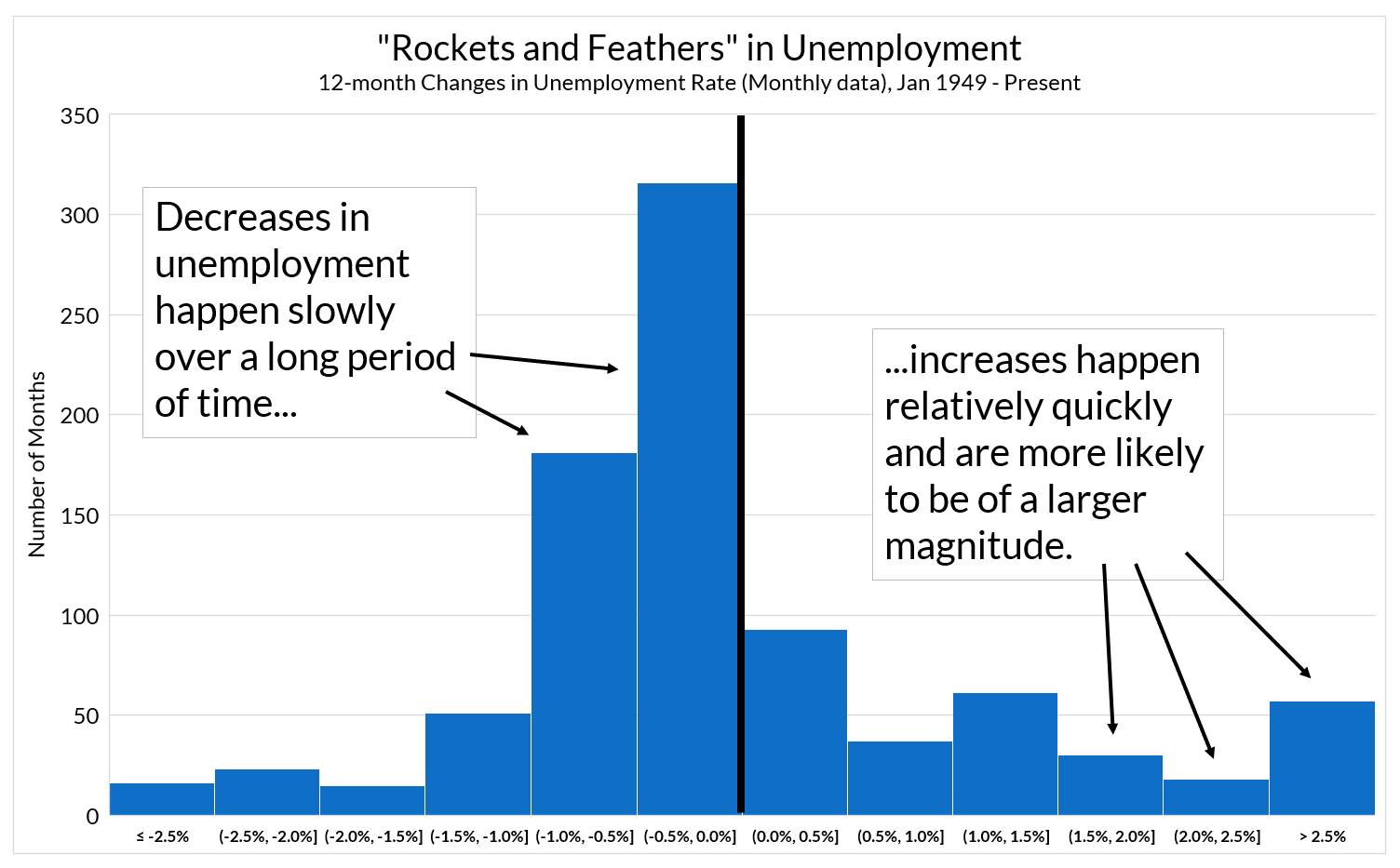

To be clear, we are not saying that there are sure-fire signs that a recession is around the corner. What we are saying is that the balance of risks between inflation and unemployment has flipped, relative to a year ago (the Fed has somewhat acknowledged this shift as well, describing the risks as “more balanced”). The key dynamic to keep in mind is that gradual increases in unemployment are rarely contained. For all the talk of “rockets and feathers” in inflation, the same can easily be said for unemployment. Increases in unemployment are generally rapid, whereas decreases are much more gradual.

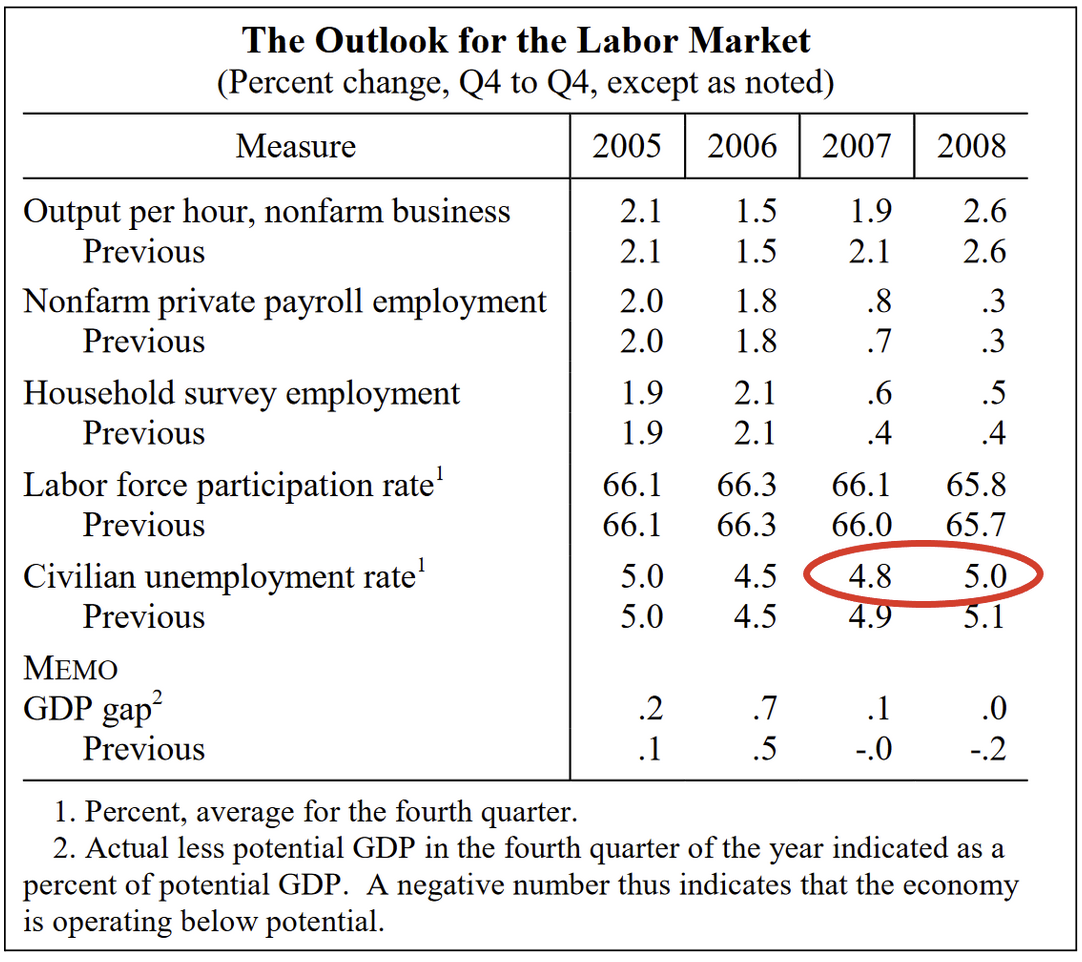

What this means for the Fed is that they need to be proactive in staving off labor market risk. They can’t wait to see the whites in the eyes of unemployment before acting; by then, it’s already too late. It wouldn’t be the first time the Fed has made that specific misstep either: 1990, 2000 and 2007 all saw a Fed which failed to fully appreciate unemployment risks and waited too long to react to a deteriorating labor market. Take, for example, the Fed’s actions in 2007; they were presented with a forecast of rising unemployment and opted to hold rates steady instead of cutting, citing inflation risks.

“The risk that inflation will fail to moderate sufficiently, however, remains significant and material”

Vice Chairman Geithner, May 9th 2007 FOMC Meeting

The longer Fed policy rates stay this high, the more recessionary risk the economy will be subject to. For now, the economy and the labor market have been more resilient to the Fed’s rate hikes than most, including the Fed, have expected. While there is some disagreement about whether the lags and magnitudes of the effects of monetary policy have changed, there is good reason to think that the recessionary risk of holding rates steady will only increase from here.

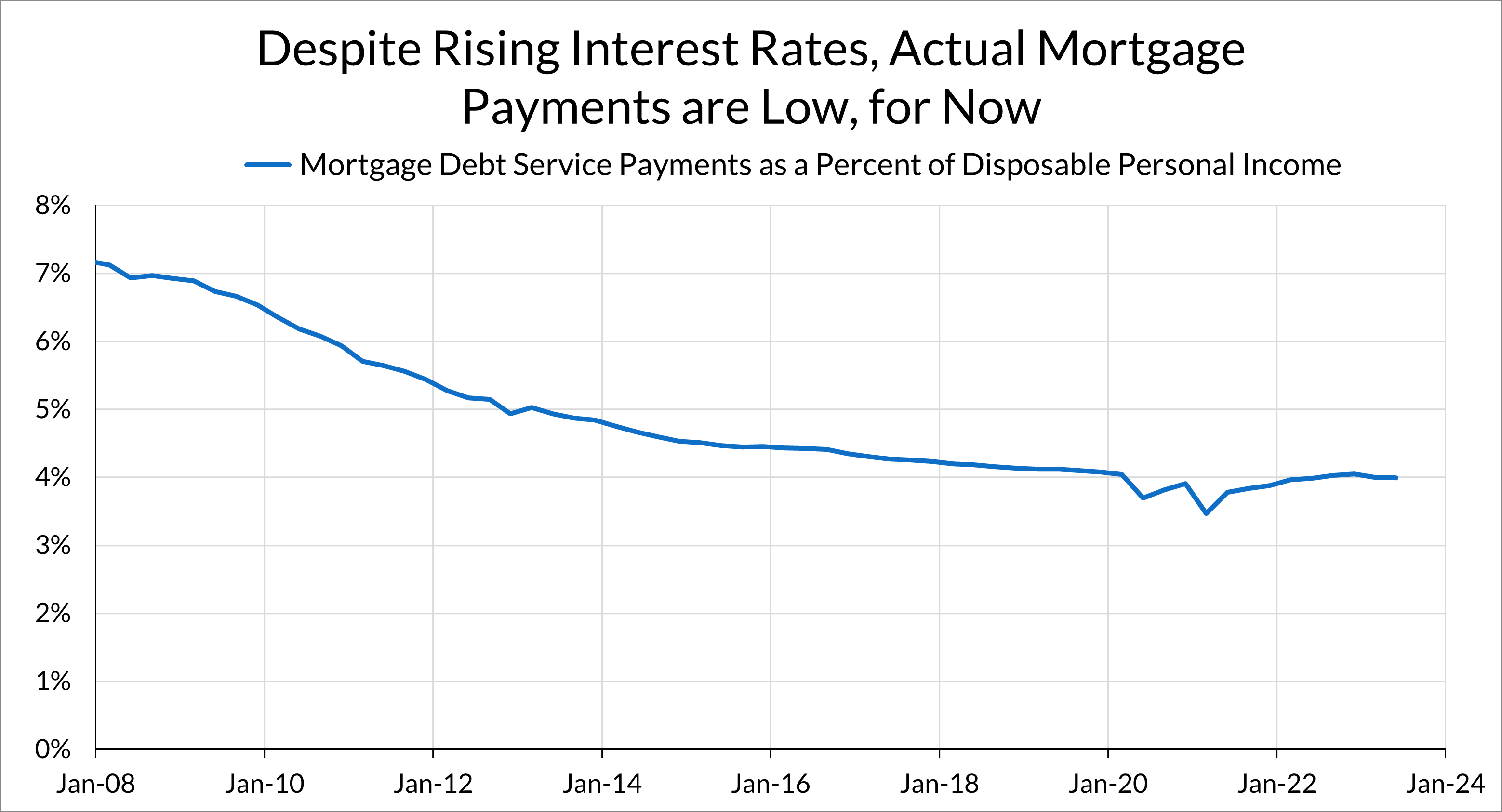

Take mortgage rates, for example. While the Fed’s tightening has raised mortgage rates to levels not seen since 2000, the interest rate on outstanding mortgages has not increased by much at all, due to the large portion of mortgages originated before the rate hikes. While this has effectively frozen the real estate market, actual mortgage payments as a percentage of disposable income has remained insulated from interest rate hikes.

A similar dynamic is taking place in corporate debt, where most outstanding debt was financed before the recent rate hiking cycle. While these two dynamics have helped insulate consumers and businesses from Fed tightening (and thus help protect consumption and employment), these insulating factors will erode over time. Eventually, corporate debt needs to be rolled over and households need to move. As that happens, the long and variable lags of Fed policy will begin to present a growing drag on consumption, investment, and employment.

“If we say that the cost of their borrowing to do those things is now a little bit higher than it was two years ago…. Maybe I’ll hire less people. Maybe I won’t set up that factory. Maybe I’ll cut production by 10 percent. I might close down a factory. I might fire people.”

Atsi Sheth, Managing Director, Moody’s

The economy is due to face a number of other headwinds in the next year beyond Fed tightening. The rapid labor income growth that came with the rapid recovery in employment and tight labor market won’t be there in 2024. Demand from “revenge” travel and services consumption after the pandemic is likely to be less important. While there is considerable uncertainty about the magnitude of remaining insulation in household balance sheets, perceived or real depletion of liquid assets is likely to be a larger economic drag in 2024 than 2023.

Strategic Implication: Front-Load Rate Cuts

The speed, size, and durability of the Fed’s hikes so far presents the possibility of nonlinear downside risk. Recession is not our base-case, due to recent economic resilience. However, we do see elevated risk of nonlinear recessionary dynamics without policy rate normalization, relative to the normal probability of recession in any given year. Most hiking cycles in recent decades tend to be the proximate cause of “something breaking” (stock market, housing market, banking institutions, etc). While reactive responses can sometimes be sufficient to prevent recession (e.g. 2018-19), there are times when they prove insufficient (e.g. 2000-2001).

For Fed policy, these risks should encourage Fed officials to frontload cuts (or signals about cuts) for the purposes of normalization. The financial risks associated with high interest rates can hit unpredictably, nonlinearly, and very quickly, as the failure of SVB and other financial institutions earlier this year demonstrate. While a 50 basis point “normalization cut” might be generally too swift a pace to maintain throughout the whole process, the most justifiable time for such a large cut would be at the outset: better to and get under 5% sooner rather than later.

For now, the Fed is doing exactly the opposite—not only are they not indicating a cut in early 2024, most FOMC members are refusing to talk about the prospect of cuts at all. Neel Kashkari even went so far as to say they are not even talking about the prospect of rate cuts amongst themselves.

Assuming sufficient disinflation to justify 200 basis points of normalization, the first 100 basis points of cuts should materialize more quickly than the subsequent 100, especially since the Fed is likely to be abundantly cautious and reluctant before initiating the first interest rate reduction. As the Fed gets closer to the ballpark of the neutral interest rate, it may be prudent to slow down the pace of easing further, even if core inflation justifies further easing. The potential inflationary effects of past interest rate cuts and the location of the neutral interest rate are both uncertain and grow in salience as interest rate normalization advances.

Using our own gross labor income framework, there are growing signs of slowdown, and while not all slowdowns lead to recession, all recessions begin with a slowdown. The elevated probability of recession (in the absence of any easing) would imply that gross labor income performance is also liable to breach a reasonable “floor” growth rate, even if you take a conservative view of productivity trends, labor market slack, and labor force growth. If recession probabilities become more decisive, the case for easing is straightforward.

As it stands now, the risk of slowdown is a meaningful balancing factor in favor of easing, at least so long as policy rates remain so elevated while gross labor income growth rates continue to endogenously cool. Should the odds of a sustained inflation overshoot also diminish (or even suggest an undershoot), the elevated probability of nonlinear downside risk scenarios should bolster the case for lowering interest rates.

Inflation Consistency, Legibility and Credibility

Policy Motivation: Be Consistent on Inflation

From 2022 through mid-2023, the Fed repeatedly underestimated the persistence of inflation and consistently revised the interest rate path upwards in light of this data. Most financial market and real economic participants understand that interest rates are substantially higher than previously expected due to high rates of realized inflation in the recent past. Whether or not you agree or disagree with the particular path the Fed has chosen, that policy has largely been legible to the public up until this point.

Now, the Fed finds itself in the reverse situation: inflation has consistently come down faster than expected. Both consistency and credibility imply that the Fed should respond analogously to favorable inflation developments. To be more precise, the latest core PCE growth rates are 3.5%, 2.5%, and 2.4% on a 12-month, 6-month, and 3-month basis, respectively. The current year-on-year growth rate of core PCE is not only undershooting the June and September 2023 SEPs, which show a terminal rate of 5.6%, but even undershooting the SEPs from December 2022 and March 2023, which project a terminal rate of 5.1%.

That is, when the Fed raised interest rates to their current level at the July FOMC meeting, the inflation trajectory looked a lot worse than it would turn out to be. In the past, surprisingly high inflation data was an impetus to raise the federal funds rate path; to maintain credibility today, the Fed should be prepared to do the opposite when inflation comes in softer than expected.

The Fed is already somewhat aligned by signaling that they will hold rates steady in December (instead of another hike, as previously projected), but the case for reducing interest rates may arrive at the Fed’s doorstep more quickly than they are currently thinking or communicating. The recent disinflation has given the Fed room to cut in early 2024, which they certainly should exercise if there is growing risk of rising unemployment.

If lower inflation fails to translate into lower interest rates, the legibility of the Fed’s policies would substantially deteriorate. Some financial market participants and Fed commentators have predictably speculated that the “neutral real interest rate” is now structurally higher than before the pandemic. If the Fed were to lean heavily on this justification, we doubt this would hold up as legible to the real economic participants trying to make critical judgments about the path of future macroeconomic and interest rate outcomes. Worse, such a justification, if leaned on aggressively, looks like a kind of fudge factor. The Fed’s own assumptions about equilibrium would become a de facto function of where policy rates are set today and foment more unstable expectations about the future path of interest rates. Does the tail wag the dog?

Obviously, the flip side of this is that the Fed is concerned that cutting (or even talking about cutting) too early may lead to an inflation resurgence. Understandably, they would like to be absolutely sure that inflation is on the path to 2% before easing. One main reason proffered for the need to act aggressively against inflation after the pandemic was the importance of ensuring that inflation not get “entrenched” due to unanchored expectations or wage-price spiral dynamics.

We were always skeptical of those stories, but now, in any case, the data suggests that the probability of an imminent resurgence is diminishing and that the prospects for “wage-price persistence” and entrenched inflation are diminished. Wage growth is approaching a pace the Fed considers consistent with 2% inflation and in a manner that defies explanations rooted in the unemployment rate, job openings or other conventional measures of labor market slack.

With that in mind, it is not surprising that Fed officials trying to keep the door open to further rate hikes remain vague about the sources of inflation risk. The reasons and evidence for elevated inflation risk proffered earlier—rising expectations and wage growth—are falling away. Some officials (such as Barkin and Waller) have pointed to the growth trajectory, especially in light of a very strong Q3 GDP report, as one reason to remain as vigilant against inflation as they are. But to the extent that this growth represents productivity growth, the Fed should welcome that progress rather than fear it, especially for inflation reasons.

In any case, the Fed justified raising the interest rate path on the basis of upside inflation surprises. They should at least remain symmetric on the way down.

Strategic Implication: Follow Inflation Down

The Fed should lower interest rates at a pace roughly proportional to progress on inflation. Even if the Fed initially keeps rates well above what benchmarks like “Taylor Rules” would prescribe, the general principle should still be that the more inflation comes down, the further interest rates should be lowered in kind.

While we don’t endorse the use of such strict rules for monetary policy, those rules have already served as aspirational upper bounds in the Fed’s hiking cycle calibrations. In fact, Waller has already alluded to thinking about the response of interest rates to disinflation along these terms. Symmetric sensitivity is ultimately warranted, even if it materializes with a lag.

"If the decline in inflation continues “for several more months . . . three months, four months, five months . . . we could start lowering the policy rate just because inflation is lower. It has nothing to do with trying to save the economy. It is consistent with every policy rule. There is no reason to say we will keep it really high. [emphasis ours]”

Christopher Waller, Nov. 28th, 2023 at the American Enterprise Institute

It’s worth noting that, relative to these policy rules, monetary policy is already too tight. The Cleveland Fed estimates federal funds rate targets under 7 different policy rules and 3 forecasts of inflation and economic activity. Except for a particular “first-difference rule” (which calls for hikes as long as inflation remains above target), the current federal funds rate target is above the prescription under every combination of monetary policy rules and forecasts.

Most of these rules are based on the premise that for every 100 basis points of change in the underlying inflation rate (which turns out to be very difficult to gauge amidst a battery of shocks), policy rates should be adjusted 150 basis points (1.5 is a common coefficient on inflation in benchmark Taylor Rules and their variants). If the current inflation overshoot (~150 basis points) erodes over the next 4-5 quarters, the pace of implied policy rate reduction would amount to an average of 25 basis points every FOMC meeting (225 basis points total). This is a general prescription for the trajectory, but not a rigid proposal that the Fed move in lock-step with inflation prints. As we have noted earlier, this process of interest rate reduction is likely to lag inflation and Taylor Rule outcomes, and there might be good reasons to take a frontloaded approach, one that proceeds slower as the normalization process advances.

Under our own gross labor income framework, disinflation by itself can justify easing policy, but easing would be proportional to the probability of an inflation undershoot relative to the Fed’s 2% target. Right now the probability is rising but still low. If disinflation continues into the spring of next year, the risks of an undershoot will likely grow. Alongside elevated recession probabilities, the case for easing can foreseeably gain critical mass next spring even if we don’t see visible labor or financial market deterioration. Thus, in practice, a lagged response to implied Taylor Rule prescriptions are more similar to the specific first-difference rule our preferred Fed framework would lean upon.

Policy Motivation: The Supply Side Matters

Throughout the arc of inflation and disinflation, Chair Powell has consistently acknowledged the important role that supply-chain disruptions and recovery have played. Going forward, Powell is thinking about whether or not there is room for further disinflationary supply-side developments. Take this statement from his opening speech at the IMF last month:

"While the broader supply recovery continues, it is not clear how much more will be achieved by additional supply-side improvements. Going forward, it may be that a greater share of the progress in reducing inflation will have to come from tight monetary policy restraining the growth of aggregate demand."

Jerome Powell, 24th Jacques Polak Annual Research Conference at the International Monetary Fund

We think there’s still room for disinflation from the supply side. The NYFed’s Global Supply Chain Pressure Index (GSCPI) has fallen to its lowest level in the series’ history, and should provide continuing disinflation in the short term as firms adapt pricing and production to the environment. Meanwhile, the full force of fiscal support from IIJA, CHIPS and IRA for investment and, by extension, medium-term price stability, has yet to come.

Oddly, Powell talks about the supply side as if it is determined upstream from monetary policy: the supply side may or may not recover more, and Fed policy will simply respond to whichever happens. We think that a full reckoning with the effects of the Fed’s tightening efforts on the supply side is needed to fully understand how to think about the supply side and the inflation trajectory. A recent spate of research shows that tight monetary policy reduces investment in innovation and, in some models, can even backfire on the inflation front in the context of a supply shock.

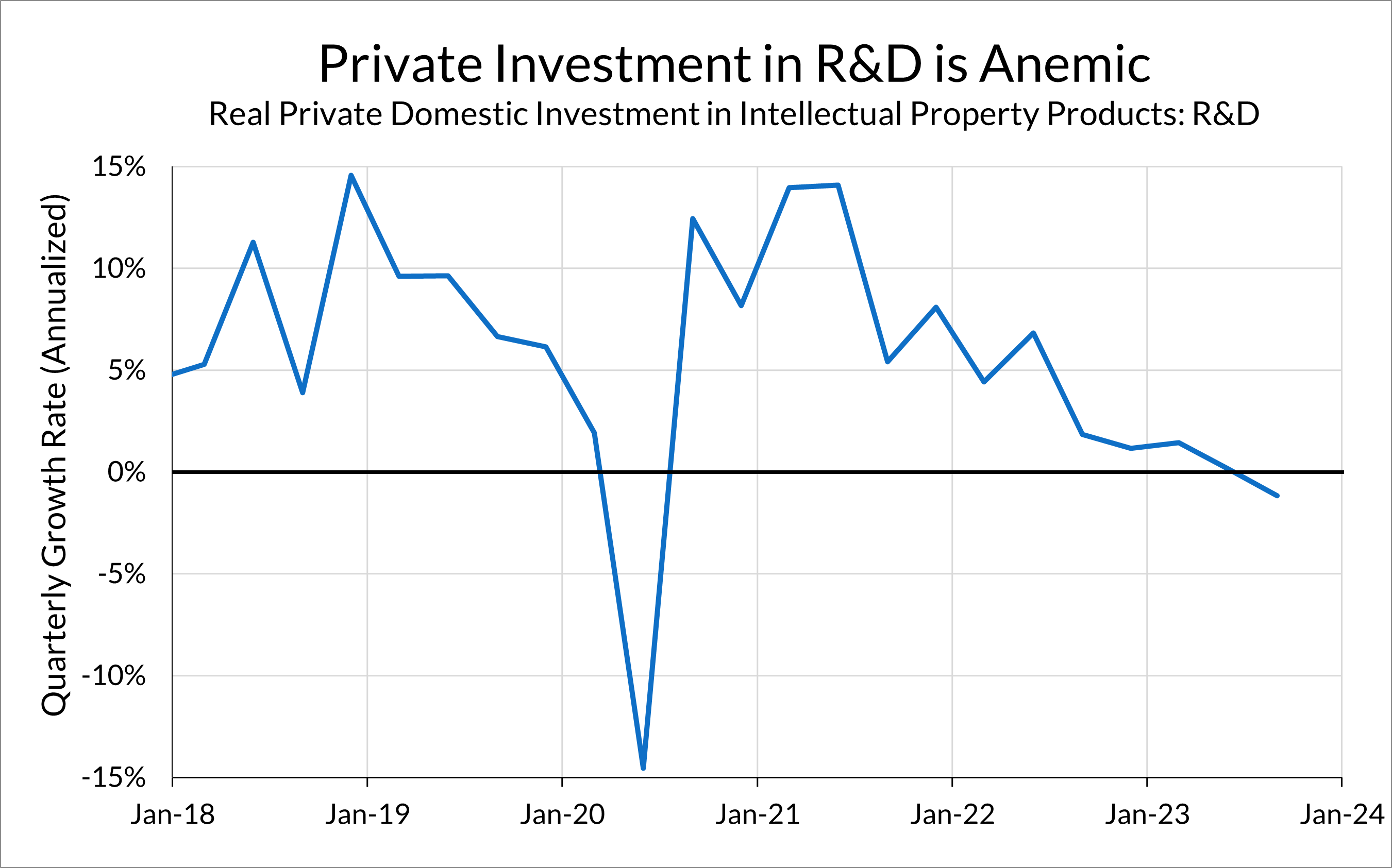

In fact, it already appears as though Fed policy is slowing down investment. Since the beginning of the hiking cycle, private investment in innovation investment has slowed substantially. Spending on private research and development investment actually shrank in Q3.

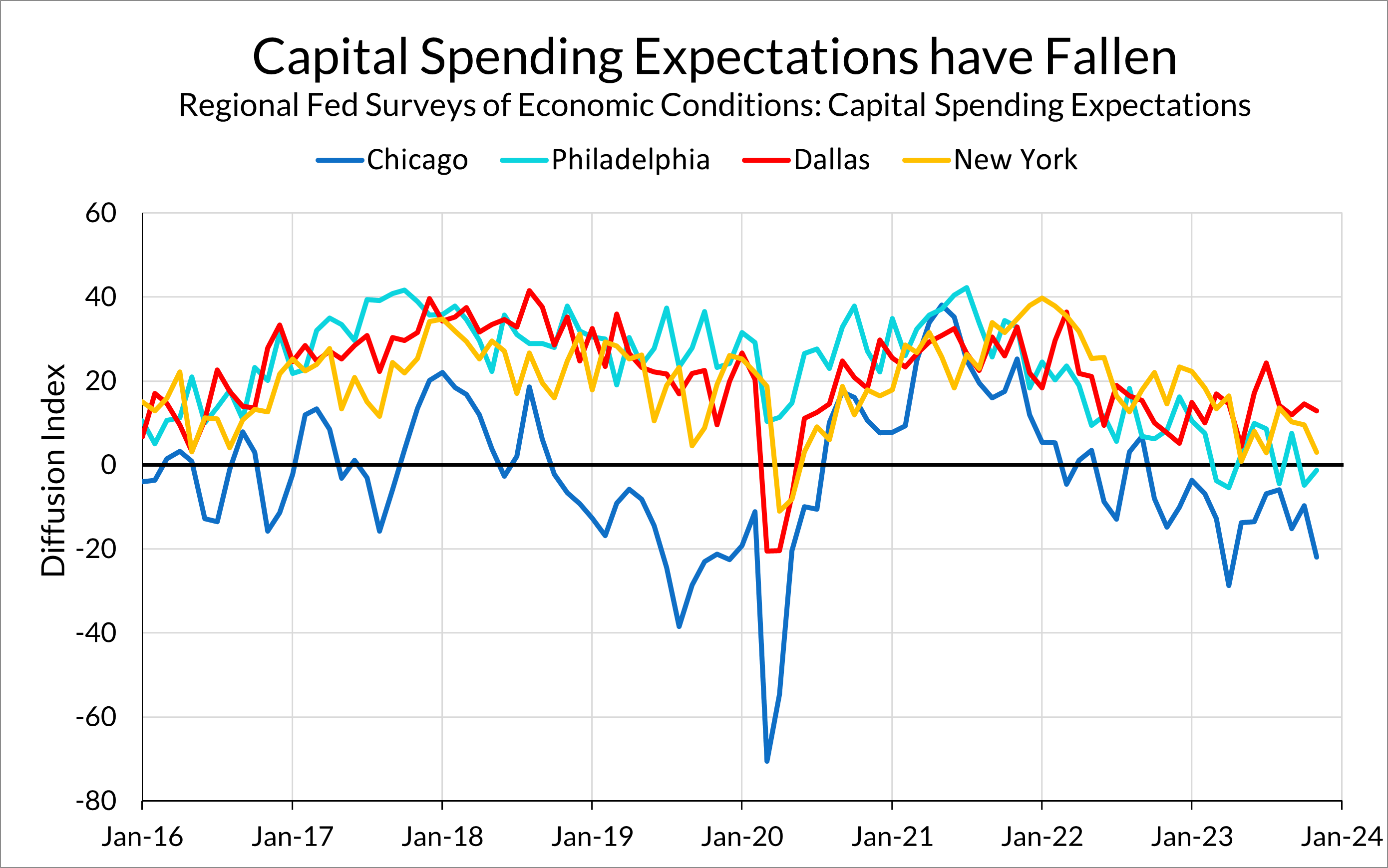

The Fed’s rate policy drag on investment is not only felt in the innovation sector. Across many regions and industries, regional Fed business surveys are reporting that they are planning on cutting investment and capital expenditures.

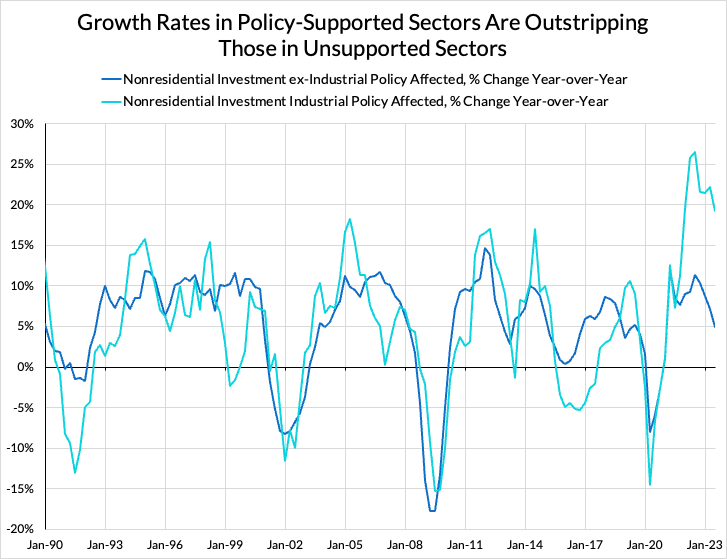

What strength there is in investment appears to be driven by sectors that are bolstered by fiscal support through policies such as CHIPS and IRA. Outside of those sectors, investment growth has taken a step back as the Fed has tightened policy.

If we look into specific sectors, we can see signs of the investment slowdown. The most recent ISM Manufacturing PMIs offer a range of anecdotes illustrating this slowdown. Almost all respondents noted the slowing economy: in Computers and Electronic Products we hear, “Economy appears to be slowing dramatically. Customer orders are pushing out.” In Chemical Products, respondents are “[s]tarting to feel softening in the economy.” One respondent in Machinery Manufacturing makes it plain: “The end of the major construction season and an early pullback in customer capital expenditures purchases have resulted in a lower backlog in the fourth quarter.”

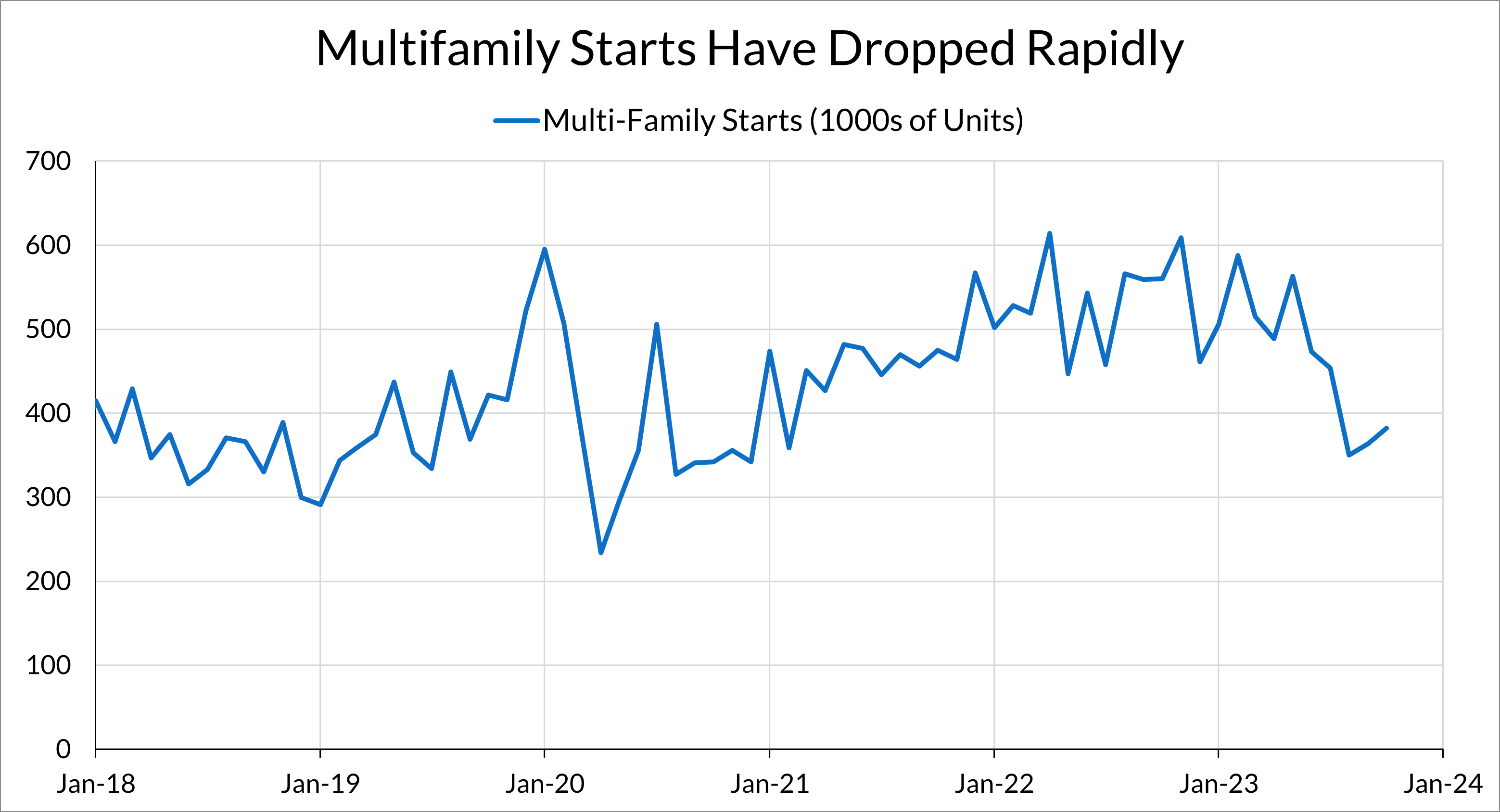

These trends are especially concerning in sectors which have played a large role in the most recent spate of inflation. Take housing, which Austan Goolsbee thinks is especially pivotal to the inflation outlook in 2024 and comprises a large portion of the personal consumption basket. Multifamily starts have cratered in the past few months, potentially exacerbating rental inflation trends in 2024 and beyond as the pipeline of new apartments dries up.

Meanwhile, energy projects in nuclear, hydrogen, wind, and solar have been hit especially hard by the rise in borrowing and capital costs. Given the important role that energy shocks have played in this inflationary episode, slowing investment in energy may sow the seeds for greater price stability risk down the road.

The Fed, as Powell would stress, does not have an investment mandate, nor does it have a climate mandate. But, this doesn’t mean that the Fed can ignore its effects on the supply side. In fact, the inflation mandate is precisely why the Fed needs to be concerned about the impact it’s having on investing in the productive capacity of the economy in order to avoid physical capacity shortages causing inflation flare-ups in the future. Slowing demand by slowing investment (and demand) might reduce inflation in 2024—but it may come at the direct cost of constrained supply and increase vulnerability to inflationary pressures for years to come.

Strategic Implication: Maintain Optionality and Stay Data-Dependent

The Fed should take an open-ended, data-dependent approach to interest rate normalization. An approach which sets the scope for interest rate normalization in advance takes an excessively static view of the supply-side dynamics and undervalues the optionality at play. Just as we advised the Fed to “learn and adapt” as they raised interest rates incrementally, we would look for the same approach in interest rate normalization.

If supply-side forces are supporting growth – especially in fixed investment – while continuing to contribute further disinflation, the scope for interest rate normalization might be larger than anticipated. While it is common to associate increases in fixed investment and productivity growth with a higher neutral interest rate (“r-star”), this association ignores how such dynamics can support higher levels of non-inflationary levels and growth rates in employment and output over time. Better supply-side performance does not necessarily imply higher interest rates, especially if that performance is also part of how inflation outcomes stay contained over time.

On the other hand, adverse supply-side developments may materialize alongside policy easing. For example, if the dollar depreciates in a manner that stokes global commodity demand and a commodity price supercycle in the process (as occurred in the mid-2000s), it might limit the desirable scope of normalization. Above all, these judgments are highly context-dependent and best made through reading-and-reacting, rather than via rigid anticipation.

Data-dependence is a two-way street. Our preferred framework actively endorses a data-dependent forward-looking approach, both for demand-side and supply-side dynamics. For now, we see strong evidence that initial efforts to normalize interest rates should unlock some non-inflationary growth in fixed capital formation. The full scale of this dynamic and countervailing dynamics will only be known as the Fed proceeds further on the normalization path, and requires the Fed to fully appreciate the breadth of the impacts and effects of its monetary policy actions.

Conclusion

Achieving the soft landing would be a historic win for the Fed. A fall in inflation of this magnitude without a recession has few historical precedents. Given the considerable shocks the US economy has faced over the past three years, bringing inflation down while maintaining the incredibly rapid post-pandemic labor market recovery would be a tremendous achievement. While the Fed was less certain this was achievable earlier this year, they’ve since started to see this goal as a real possibility.

Now inflation is falling faster than expected, the Fed finds itself in a situation where the risks are shifting away from inflation and towards unemployment. The Fed claims to be data dependent; as those risks shift, so too should Fed strategy. And even if Fed officials are reluctant to talk about it now, that means it’s time to start talking about how to renormalize interest rates from above as we hopefully continue to follow the “golden path” to a soft landing. We hope that the motivations and strategies we’ve outlined will bring clarity for Fed officials, commentators, and market participants as to the way to stay on that golden path.