By Alex Williams and Skanda Amarnath

There is a long tradition of describing recessions based on what letter their aggregate data looks most like when plotted against time. The only difference between a U-shaped recession and a V-shaped recession is how long the economy spends at the bottom, while in an L-shaped recession the economy hits bottom and doesn’t leave. If the economy recovers, but then slips into recession again, we call it a double-dip or W-shaped recession. However, the COVID recession was so unprecedented in its severity and aftermath that commentators are now calling it a “K-shaped recovery.”

The recovery feels complete for those who were already of means and yet has barely begun for low income-earners. However, we know that recessions always impact different income groups in different ways. Recessions create weak labor markets which reduce wages for marginalized and low income workers, and may even drive them out of the labor force. It then takes a sustained expansion to draw them back in, as we have pointed out elsewhere. In a way, the K shape is common to all recessions. If we are to have the best policy response, we must think clearly about the ways that the post-COVID economy is unique.

To this end, recent labor market data releases make an interesting case that we are actually facing two independent recessions, each with their own intensity, timeline, and optimal policy response. We could call these two impulses The Shock and The Slog. The Shock started in early March and ended within a couple of months. Heavy-handed yet necessary public health policies cut employment, while the generous benefits of the CARES Act sustained consumer spending. As such, the worst of the drop only lasted a few weeks, with Neil Dutta boldly noting in late April that economic activity had already bottomed.

While The Shock may have ended, labor market indicators suggest that we still need to respond appropriately to The Slog if we are to avoid a repeat of the lackluster “jobless recovery” following the 2008 crisis. The demand-side fallout from The Shock and the ongoing set of uncertainties has the potential to disrupt labor markets for years to come. Declaring victory over The Shock does not mean that the need for stimulus has passed. It simply means that the response must be tailored to a labor market that is still atrophying following a period of extreme disruption. As such, we cannot allow signs of short-term improvements to overshadow deterioration under the surface.

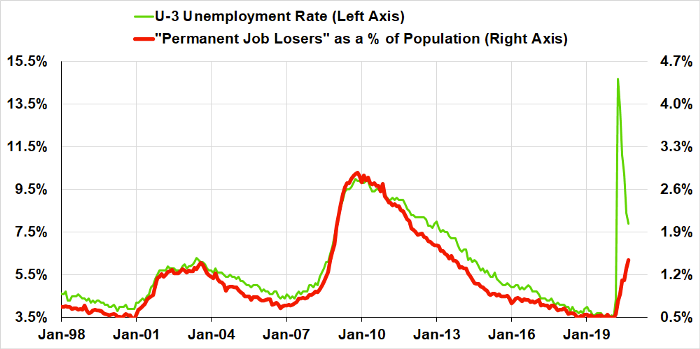

Temporary layoffs have declined steadily since the onset of the pandemic, with the total number of workers falling by 2 million in September. The headline U-3 unemployment rate has also continued to fall, dropping a further half percentage point. By most measures, the labor market has recovered about half the ground initially lost in March and April.

Commentators have noticed this as well. There is a building narrative that the CARES Act stimulus succeeded in preventing a serious recession, and that current risks are now to the upside. Fed-watcher Tim Duy has been arguing this for weeks, and Vice Chair Clarida concurred in a recent speech that the “recession may already be over.” Headline equity market indices are through their pre-COVID peaks, with performance especially strong among businesses that have proven to be especially resilient to the COVID recession. Most business and consumer sentiment indicators signal expansion. Even if there is no vaccine in the near future, we now have a better understanding of the virus and the public health interventions it requires. Across-the-board lockdowns seem less likely going forward.

While many headline economic releases have signaled the end of The Shock, the details within those releases now signal a different type of deterioration in the labor market. The Slog may have only just begun. For one, the composition of unemployment is steadily worsening. As The Shock has played out, the demand loss brought on by the initial set of shutdowns has filtered through to the rest of the economy. Even as the unemployment rate is falling, more workers are experiencing permanent, rather than temporary, job loss. We are beginning to see substantial permanent layoffs well after the initial onset of the COVID crisis. The scale and speed of permanent job losses are on par with those of fall 2008.

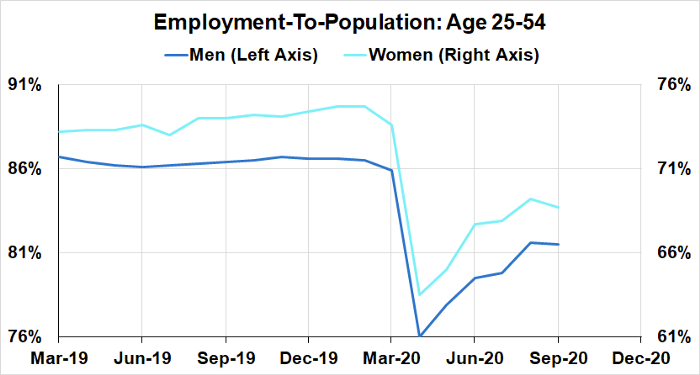

Softening in the prime-age employment-population ratio (EPOP) in September reveals a similar dynamic. Prime-age employment is substantially below pre-pandemic levels, and yet the September report already seemed to indicate some backsliding from the observed recovery earlier this summer, for men but especially so for women.

It may seem hard to square this weakness in prime-age EPOP with steadily falling unemployment rates, but recent research confirms that employment-to-population ratios are the more reliable gauge of labor market health. There is no reason to think that roughly three percent of all men and women between the ages of 25 and 54 would have decided to voluntarily leave the labor force in the last seven months without the pandemic and its long term fallout. The status of schools and childcare remains highly uncertain, and variable by region. Given these facts, the improvement brought about by prior fiscal stimulus may be stalling out after regaining less than half the lost ground.

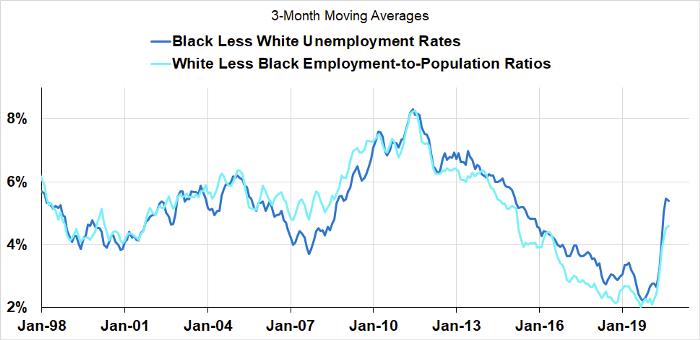

We also see in the September jobs report a labor market that is getting more unequal as it stalls. The unemployment spread between black and white workers expands in recessions, and shrinks as the benefits of long-lasting expansions filter out to underserved populations. We see a clear increase in the spread in the chart below.

It is also important to remember that medium-term uncertainty remains with us. We are no closer to knowing when or if a vaccine will become available than we were at the start of the crisis. At the same time, fiscal policy uncertainty necessarily implies uncertainty about the future trajectory of corporate profits, household incomes, hiring, and investment. The medium-term sectoral impact of the virus will thus be particularly difficult to predict.

The key is to now think about what it would mean to recognize these are two related but separable phenomena, each with its own timeline. Simply celebrating the end of The Shock and calling it “Mission Accomplished” risks ignoring the costs associated with allowing The Slog to persist and impair longer term labor market health. Vice Chair Clarida’s optimistic comments mentioned above were, after all, made in the context that it will take substantially longer than another year “for the unemployment rate to return to a level consistent with our maximum-employment mandate.” While there are certainly scenarios in which the economy makes a swift recovery, monetary and fiscal policymakers should be sensitive to the balance of risks and have every reason to err on the side of additional action to support a robust recovery.

If we take the Shock and Slog to be separate recessions, they seem to require distinctly different policy responses, even if the ultimate objectives are the same. The CARES Act worked very well as a fleet-footed response to The Shock. The Slog, however, will need a more complex set of fiscal supports over a much longer timeline, something that a “timely, temporary, and targeted” short-term approach risks falling short of.

Given that the labor market may be deteriorating on a more sustained basis now, we should look to implement longer-term extended UI, augmented with federal triggers for higher payouts should the downside of The Slog ultimately overwhelm the recent recovery from The Shock. Key industries that we would like to remain competitive in after this is all over — tourism, transportation, an endless array of services — will require sustained support. If we wish to take seriously the possibility of trade and supply chain disruptions related to the current and future pandemics, industrial policy that builds back domestic productive capacity will also be critical. These are just a few examples, and it may be too soon to judge which measures are of highest priority. However, all told, the labor market data present some worrisome signs that we may be in the second inning of a much longer slump.