Joelle Gamble Copeland most recently served as Deputy Director at the White House National Economic Council. Prior to that, she was Chief Economist for the Department of Labor. The views represented here are solely of the author and do not represent the views of her past or future employers.

Introduction

If I were to ask you to name the first image that comes to mind when you hear “American auto industry,” what do you think of? Probably an assembly line in Michigan or Ohio or a dealership lot stacked with large trucks. You would not be wrong. Those images do reflect the reality of one of America’s most economically important industries (Note 1). But they are not the full picture. By number of firms and employment, most of auto manufacturing is in parts manufacturing (Note 2). These small and medium-sized companies make components for large automakers—from metal stamping to axles and engine parts to software–in nearly every state in the union. With unevenness in product demand from the clean energy transition and fierce international competition, the U.S. domestic auto supply chain faces serious headwinds.

This brief proposes a role for the public sector in sustaining the auto supply chain and offers policy recommendations that a future Administration and Congress can implement to strengthen auto supply chain companies, boost quality employment and foster American competitiveness in the race to win the global auto market.

Why invest in the auto supply chain?

A modern auto supply chain, with the capacity to retain workers and supply

the clean energy sector, is critical to the auto industry’s ability to make quality,

affordable vehicles to compete globally. Investing in suppliers will increase U.S.

productive capacity, support local employment and help communities capture

the positive economic spillovers that come from making products in America.

Sustaining suppliers is integral to building an enduring U.S. manufacturing base

that can meet America’s economic and national security objectives.

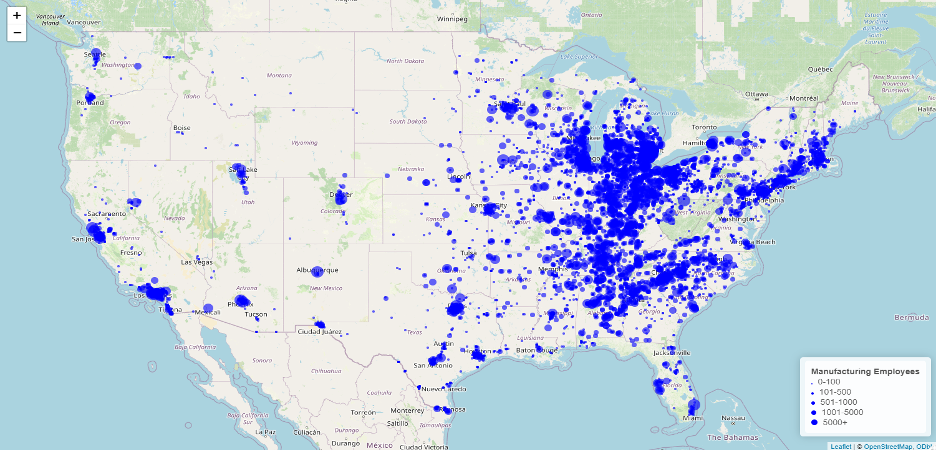

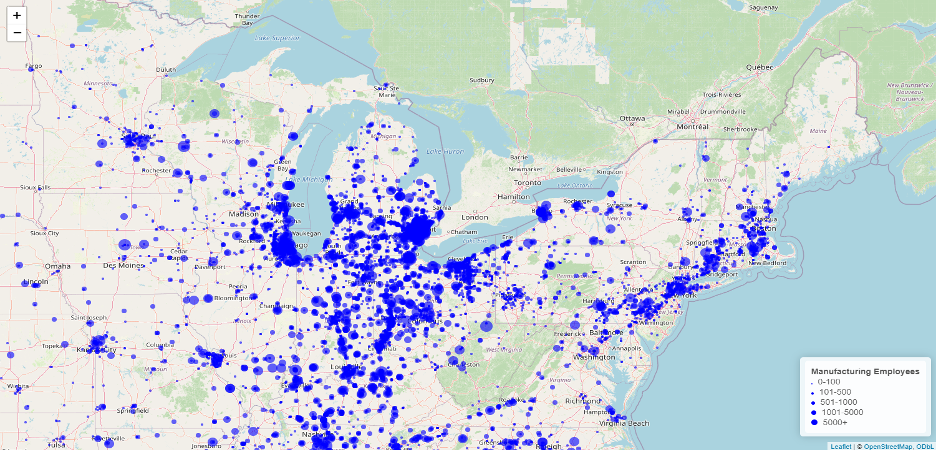

Much of the public conversation on supply chains has focused on their sprawling,

global nature. For the auto industry, North America, and the U.S. in particular,

houses a significant share of its supply chain (Note 3). Parts manufacturing–excluding vehicle bodies and trailers–was over half of auto manufacturing employment in 2023 (573,000 jobs) (Note 4). And there are thousands of auto suppliers across the United States (Note 5). This is likely an underestimate as manufacturers in other industries–like metals and electronics–also supply the auto industry. This brief focuses primarily on parts suppliers to automakers. However, there are also companies that supply service parts that help maintain the hundreds of millions of vehicles on U.S. roads.

SOURCE: Auto supplier corporate and manufacturing sites by employee count. Data courtesy of Elm Analytics, LLC. From the Numerus™ Online Automotive Database

The close proximity of suppliers to automakers matters from a supply chain risk management standpoint as companies increasingly shift to near- or onshore production to avoid the costly disruptions that often come from environmental and geopolitical exogenous shocks to global transportation routes. Manufacturing processes are also a source of knowhow and innovation. As the U.S. seeks to build more advanced manufacturing and technology clusters, there is opportunity for innovation spillovers to move along supply chains (Note 6). Many auto suppliers are also anchor employers in their communities, which are urban, suburban and rural.

A potent combination of macroeconomic headwinds (i.e. high capital costs),

uncertainty of demand for clean vehicles, and often-subsidized international

competition to supply automakers complicate the future of domestic auto

suppliers. The clean vehicle transition requires internal combustion engine (ICE)-

only parts suppliers to retool if they intend to supply clean vehicle parts or other

industries in the long-run. Yet, in the short-run there is minimal clarity on the

length of the ramp-down in demand for ICE-parts. Retooling is costly and running

product lines for both ICE and clean vehicles is not always profitable. Clean

vehicle-only suppliers are also racing down the cost curve for battery production

in order to secure customers, shore up project-financing (which requires a

customer base) and compete with international companies, including those in

the People’s Republic of China. On top of these dynamics, smaller suppliers have

difficulty accessing capital as they are often lower margin and revenue from

clean vehicle capital projects is tied to certainty in clean parts demand (Note 7). Even top auto suppliers, which are large businesses like Bosch, Magna and Lear had lower margins than the automakers coming out of the pandemic as they were squeezed by rising input costs (Note 8).

There is an opportunity to help the auto supplier base navigate economic

headwinds and the clean energy transition. Investing in retooling and facility

upgrades can boost company competitiveness, cybersecurity and improve worker

safety. Trade policy that advantages high-road practices and lowers barriers to

accessing export markets for suppliers can complement other competitiveness

policies. Finally, support for common sense approaches to boosting labor supply–including investing in communities with an existing pool of autoworkers–can

boost companies’ productive capacity. The public sector plays a role in facilitating

these actions.

What is the Role of the Public Sector?

During the pandemic and subsequent geopolitical shocks (like conflicts in Ukraine

and the Middle East), snarled supply chains sent goods inflation skyrocketing

and made it harder for Americans to access daily needs like food and medication.

Many Americans learned how important the ability to move goods and parts

around the world was to their daily lives and for the ability of American

companies to make the products they use daily–like cars and trucks. In response

these acute disruptions to supply chains, the federal government, in coordination

with private companies, state and local leaders and non-profits, took a more

active approach to implementing policies that improve supply chain resiliency or

solve acute disruptions and bottlenecks (Note 9).

Private companies manage supply chains. Competitive markets incentivize companies to maximize efficiency and productivity in a manner that raises their bottom line. However, these market pressures do not incentivize the substantial capital investments to upgrade and maintain the infrastructure necessary for a resilient supply chain across an industry. The federal government, alongside states and localities, can and should play a role in derisking these critical investments to facilitate the movement of goods.

Federal investment can also help derisk investments and crowd in additional

private capital to build supply chain resilience across an industry. This is

particularly important as suppliers bridge the valley of death many startups face, (Note 10) including domestic critical mineral extraction and processing projects. Federal financial assistance programs can also help suppliers who need to upgrade

their facilities or retool to supply companies, whether inside or outside of the

automotive industry. Federal programs should consider being agnostic as to

which industry suppliers support after retooling, as there may not be equivalent

demand for clean vehicle auto parts as for ICE vehicle parts, given that clean

vehicles have fewer components (Note 11). Note that fewer component parts in clean vehicles may not necessarily mean fewer labor hours (Note 12).

The federal government can also partner to build local infrastructure for small manufacturers to provide capital access and support for current and future

autoworkers. By working with trusted intermediaries and locally-led coalitions

of companies, labor, schools and non-profits, federal programs are more likely to

reach their intended audiences. The current Administration has already creatively

used its existing authorities to provide support along these lines for companies

and workers in the auto supply chain, including but not limited to:

- Providing grants to states to distribute to auto suppliers who want to retool their facilities, including a recent $22 million award to a partnership in the State of Michigan (Note 13).

- Licensing a Small Business Investment Company to raise and invest

government-backed funds into small auto suppliers. Monroe Capital recently

announced a goal to raise a $1 billion fund to support small- and medium-sized

suppliers (Note 14). - Supporting manufacturers to train current and future workers on a curriculum specific to the needs of the battery supply chain through the Battery Workforce Initiative pilot (Note 15).

The federal government has recognized the strategic importance of policy to

proactively help the auto supplier base modernize to meet demand for the cars

of the future. However, they are constrained by existing appropriations and

Congressional authorities. A new Congress and Administration can build a more

flexible toolkit to sustain the auto supply chain.

Policy Suggestions

Candidates from both major parties have argued that investments in America’s

manufacturing base are important for boosting U.S. global competitiveness,

enhancing national security and sustaining quality employment. There is an

opening for a new Administration and a new session of Congress to build on

the progress made towards these goals over the last four years, using targeted

policies to boost one of the largest segments of American manufacturing capacity: small- and medium-sized auto suppliers. Unlike large, capital-intensive projects

(i.e. semiconductor fabs), retooling existing suppliers and boosting new battery

supply chain start-ups is a relatively low-cost endeavor that, with private capital,

can scale. A public investment strategy, coupled with a smart trade strategy

and policies that help America’s autoworkers, can help preserve and grow the

capacity of the U.S. auto industry.

I. Policies to modernize and grow manufacturing facilities

Federal capital programs, especially when compounded by state and local funding, can provide small- and medium-sized suppliers with access to affordable

capital with which to modernize facilities and retool production lines for clean

vehicle or other industry customers. They can also help companies building new

products bridge the valley of death. These recommendations build on existing

federal programs or bipartisan Congressional proposals. Across these proposals,

building in explicit coordination with ARPA-E funding challenges and other

programs can help companies not just catch up to today’s market but also leap

ahead (Note 16).

- Broaden the flexibility of Department of Energy Manufacturing

Conversion Grants: The Department of Energy awarded nearly $2 billion in

cost-share grants to large automakers and set aside $50 million for states to

regrant funds to small- and medium-sized auto suppliers to retool to meet

clean vehicle demand. Congress should appropriate additional funds for this

program with changes to streamline access for small manufacturers and allow

for their retooling to supply other industries, including by:- Increasing the amount of grant dollars available only for small

suppliers with a streamlined set of requirements for direct applications

to the Department of Energy and regrants through states and third-party

intermediaries; - Allowing auto supplier recipients to use federal funds to retool

production lines to supply other manufacturing industries (i.e. clean energy

and aerospace); - Codifying the Department’s approach of supporting auto workers by prioritizing projects that retain workers and have public statements of union neutrality; and

- Encouraging investments in communities with an existing supply

of manufacturing workers by prioritizing retooling proposals at the same

worksite or in the same commuting zone.

- Increasing the amount of grant dollars available only for small

- Allow the Department of Energy’s Manufacturing Office to explicitly

support qualified suppliers through the valley of death: The Department of Energy’s Manufacturing and Supply Chain Office (MESC)’ Battery Materials Processing and Battery Manufacturing and Recycling Programs are two oversubscribed grant programs supporting the construction and expansion of facilities to extract critical minerals for batteries (i.e. Albermarle U.S.), battery component manufacturing and the demonstration of products using new or recycled materials (i.e. Form Energy) . Some of these facilities are facing a valley of death, where they are at risk of running out of cash while they are securing a customer base needed to bring in more revenue and unlock project financing. Congress should appropriate additional funds for these two popular programs, including funding specifically for current beneficiaries attempting to bridge the valley of death. An additional approach Congress could take would be to authorize the MESC office to use grant funds to partner with an intermediary to build more liquid markets for upstream materials including through creative financing mechanisms such as options, forward contracts, or cost-of-differences contracts. This, in addition to the offtake agreements undertaken by Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) and other customers, would help combat artificially low PRC materials prices which are delaying or suspending domestic operations. - Restore full expensing of equipment for small manufacturers: In the

upcoming fight over the expiration of provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs

Act, Congress should restore the 100 percent deduction for machinery and

equipment for small and medium-sized manufacturing companies, specifically.

And eligibility could be limited to manufacturers purchasing equipment to

supply strategic industries, including clean energy, semiconductors, and

aerospace. Full expensing began to phase out in 2023 and will fully expire in

2027. This will take pressure off companies who want to retool but are still

deducting expenses for existing equipment.

Target existing credit programs to small manufacturers: Additionally,

it is very difficult for small companies to access subsidized credit programs

that are run nationally. There are opportunities for the Small Business

Administration (SBA) and State Small Business Credit Initiative leaders–

in states–to help break down barriers for small auto suppliers to access

government-backed loans from SBA-approved lenders and both debt

and equity from SSBCI-affiliated financial institutions. For example, SBA

could work with the Department of Commerce’s Manufacturing Extension

Partnership and states with a large concentration of suppliers to identify

and onboard financial institutions who work with the supplier base into the

lending programs.

II. Policies to grow the auto workforce

Workforce training programs and partnerships must build a pipeline of future

auto workers while remaining accessible to the current workforce. This will

help build training programs that meet future labor demand in a sector that is

grappling with technological changes and a need for workers who can adapt

to new processes and machines. That’s why this brief focuses heavily on high

schools. At the same time, small- and medium-size companies may not always

have the bandwidth or resources to build individualized workforce partnerships.

A consortia model allows multiple companies to participate in the same local program without having to set it up themselves.

- Invest in auto worker training consortia through local high schools:

To develop a sustainable local talent base for the sector, Congress should

appropriate funds to the Department of Labor’s Employment Training

Administration and Department of Education to jointly administer a

grant program to states to fund high-school based training consortia that

create clear pathways from high school to auto manufacturing jobs with

regional companies through Career and Technical Education programs and

apprenticeships. Recipient high schools should be required to partner with

local auto suppliers, union locals and community colleges to ensure that

the training partnership can serve a diverse pipeline of students, including

high school and community college students and existing auto workers

who want to train new skills. Potential examples of this approach are the

various partnerships between the Detroit Lions, the Pistons, Detroit Public

Schools and local manufacturers on programs for high school students from

underrepresented and employment-distressed neighborhoods (Note 17). - Promote labor management partnerships for financial assistance recipients: Federal financial assistance programs should require or prioritize companies with established labor management partnerships or a written commitment to form one. This is particularly important as companies navigate the clean vehicle transition and modernize their facilities. Shifts in the type of labor demanded can be better met if organizations representing workers, including unions, have an existing partnership with employers. The UAW and IBEW have already set up exemplar multi-employer partnerships (Notes 18 and 19). Example legislative text can be found here (Note 20).

- Develop a manufacturing prevailing wage: Quality wages are important

to a worker recruitment strategy. Davis-Bacon Act prevailing wages are

prevalent in the construction industry, supporting good jobs on infrastructure,

commercial and residential projects while attracting workers. There is not

a clear equivalent for the manufacturing sector and developing one would

require careful consideration of the compensation and structural differences

between the two sectors. Congress should appropriate funds to the Bureau

of Labor Statistics to field surveys and use administrative data from the

unemployment insurance accounting system develop, publish and update

a manufacturing prevailing wage database that can be used by companies

(particularly new battery supply chain companies) and policymakers alike.

Prioritizing retooling of existing facilities and greenfield investments in

communities with a history of auto manufacturing is a smart approach to solving

manufacturers’ labor supply concerns. Places with a pool of workers who understand the industry and have experience in manufacturing will cut down

on search and training costs for companies and create economic security for

workers. To recruit and retain qualified workers in today’s relatively tight labor

market, companies must offer good wages and benefits.

- Incentivize investment in “auto communities” through retooling and facility modernization grant programs: Similar to the “energy communities” framework used to encourage investment in fossil fuel communities (note 21), the Modern Steel Act (Khanna-CA) uses a “legacy communities” definition to prioritize investments in communities who traditionally produce iron and steel (Note 22). Steel is an important part of the auto supply chain–selling to both component makers and the automakers themselves. So, this framework could be broadened to include auto parts, vehicle assembly and bodies and trailers assembly to prioritize providing grants to projects in places with an existing, trained workforce. Preliminary analysis from the U.S. Treasury suggests the “energy communities” prioritization has led to significant boost in investment in these places (Note 23).

- Add an “auto communities” bonus definition to clean vehicle tax credits: Congress could add a “bonus” tax credit for the Advanced Manufacturing Production Credit, by increasing the share of the cost manufacturers can claim for domestic battery component production and module assembly if production takes place in an “auto community.”

III. Policies to level the playing field for American industry

Finally, it is important that help small- and medium-sized suppliers access other

markets to grow and diversify their business. This could either be through direct

sales or by selling downstream to customers with an export business. The Export-

Import Bank (EXIM) reauthorization process provides an opportunity to achieve

this goal.

Companies will not be able to compete without a level playing field. So, additional

trade mechanisms that prioritize high-road practices are needed, including a

cross-border adjustment mechanism and strengthening the U.S.-Mexico-Canada

Agreement in 2026.

- Reform EXIM processes to better support small and medium-sized

companies: EXIM is up for reauthorization in 2026, which presents an

opportunity to help the bank better serve its mission of supporting the export

of U.S. products and American jobs. The current Administration created a

Made-More-in-America initiative which made progress toward supporting

small and medium-sized projects by instituting a lower, 15 percent export

nexus for them. Congress should further lower barriers for small companies by increasing the default rate cap from 2 percent to 4-5 percent or eliminating it all together, allowing EXIM to take on riskier investments (Note 24). Congress could also appropriate a small sum to EXIM to help the bank cover the relatively higher transaction costs of lending to smaller companies. Congress should also codify the Made-More-in-America initiative by including it in the bank’s charter. - Implement a Carbon-Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) for select industrial imports, including iron, steel and aluminum: CBAMs can put a price of carbon leakage during the production of imported products and charge a comparable import fee. The European Union adopted a CBAM on select imports in October 2023. U.S. goods are less carbon-intensive than the global average. So, this approach, depending on the design, advantages the domestic supply chain (Note 25). There are several bipartisan proposals for a CBAM. The Joint Economic Committee has a helpful comparison chart (Note 26). Any CBAM proposal must come with resources for the Department of Homeland Security, the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Laboratories to calculate and enforce the import fee.

- Support domestic suppliers and workers in the upcoming USMCA

review: The U.S.-Canada-Mexico Agreement has a review clause that requires

all three countries to confirm whether to continue the agreement by July 1,

2026. This clause was meant to give the U.S. leverage to propose changes to

the agreement. Given developments in the auto market since the agreement

was made, the U.S. should propose several changes:- The rules of origin requirements could be ported over to electric

vehicles, not just ICE vehicles. However, if this is done, there will need to be

a reconsideration of requirements in comparison to the Inflation Reduction

Act’s 30D tax credit. If not, companies could meet the USMCA threshold

while not meeting the requirements for the tax credit. - USMCA should also address the treatment of State-owned enterprises

and facilities owned or controlled by foreign entities of concern (Note 27). - The Labor Value Content mechanism needs to change. Initial evidence

suggests that the Labor Value Content portion of the rules of origin has not

served its intended purpose of raising Mexican worker wages (Note 28). - The federal government should create a review taskforce jointly at

the Department of Labor and Department of Homeland Security focused

on generating Labor Value Content reform proposals, reviewing changes to

align domestic U.S. policy and the rules of origins, and other policy options

related to the effectiveness of these rules (i.e. tariffs), in advance of the

review deadline. The taskforce should bring together labor, economists from auto companies (of all sizes), and experts from non-profits or

universities.

- The rules of origin requirements could be ported over to electric

Conclusion

A future Administration and new Congress can make creative and decisive

policy to support the American auto manufacturing base. Through legislation

and administrative actions, they should design flexible and effective solutions to

modernize the American auto supply chain and support America’s auto workers –

who are the backbone of the industry.

Thank you to the experts who provided feedback and guidance on this report,

including Sue Helper, Dave Andrea, Jonathan Smith, Raj Nayak, Brent Parton,

Pronita Gupta, and many others. Special thanks to the Elm Analytics team for

sharing their valuable data. This report is only a reflection of the author’s views.

Endnotes

1 - The auto industry is typically 2-3 percent of annual U.S. GDP and over 3 million

jobs. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “Value added by Industry as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product” (accessed Friday, October 18, 2024).

2 - This statement just refers to the manufacturing sector. There is significant autorelated employment in the retail and services sectors.

3 - North America’s rapidly growing electric Vehicle Market: Implications for the

Geography of Automotive Production - Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. (2022).

https://www.chicagofed.org/publications/economic-perspectives/2022/5.

4 - Automotive Industry: Employment, Earnings, and hours: U.S. Bureau of Labor

Statistics. (2022, October 5). Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iagauto.htm.

5 - Hough, T. (2019, November 15). Ever wonder how many US auto suppliers

there really are? https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/ever-wonder-how-many-us-autosuppliers-really-tor-hough.

6 - Chen, S., & Liu, X. (2022). Innovation spillovers in production networks: Evidence from the establishment of national high-tech zones. China Economic Quarterly International, 2(1), 42–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ceqi.2022.03.001.

7 - Automotive Supplier Study. (2023). Deloitte United States. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/manufacturing/articles/global-automotive-supplier-study.html.

8 - This statement just refers to the manufacturing sector. There is significant autorelated employment in the retail and services sectors.

9 - FLOW. (2024). US Department of Transportation. https://www.transportation.gov/freight-infrastructure-and-policy/flow.

10 - The valley of death is the gap between having a produce and generating enough revenue to cover business costs. Companies, mainly start-ups, often go out of business during this period as they run out of cash.

11 - Idaho National Laboratory. How do gasoline & electric vehicles compare? In

CALSTART. https://avt.inl.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/fsev/compare.pdf

12 - Cotterman, T., Fuchs, E. R., & Whitefoot, K. (2022). The Transition to electrified Vehicles: Evaluating the labor demand of manufacturing conventional versus battery electric vehicle powertrains. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4128130.

13 - DOE Awards 18M to MI to help small suppliers modernize their manufacturing capabilities. (2024, August 15). https://www.michigan.gov/leo/news/2024/08/15/doe-awards-18m-to-mi-to-help-small-suppliers-modernize-their-manufacturing-capabilities.

14 - Lowery, L. (2024, October 1). MEMA, Auto Innovators to help facilitate $1B

fund for automotive industry. Repairer Driven News. https://www.repairerdrivennews.com/2024/10/02/mema-auto-innovators-to-help-facilitate-1b-fund-for-automotiveindustry/.

15 - Battery Workforce Initiative. netl.doe.gov. https://netl.doe.gov/bwi

16 - Home | arpa-e.energy.gov. (2024, October 16). https://arpa-e.energy.gov/

17 - Detroit Public Schools Community District, Stellantis and City of Detroit (Detroit at Work) partners to leverage $4 million investment to support students through Advanced Manufacturing Academy. (n.d.) https://www.detroitk12.org/site/default.aspx?PageType=3&ModuleInstanceID=22371&ViewID=7b97f7ed-8e5e-4120-848f-a8b4987d588f&RenderLoc=0&FlexDataID=53002&PageID=4920&Comments=true.

18 - About - The UAW Center for Manufacturing a Green Economy (UAW-CMGE).

(2024, October 16). The UAW Center for Manufacturing a Green Economy (UAWCMGE). https://uawcmge.org/about/.

19 - IBEW. (2024, August 6). IBEW Local Unions announce new Apprenticeship

Initiative for battery and advanced manufacturing sectors. https://csaew.com/ibew-local-unions-announce-new-apprenticeship.

20 - Text - H.R.9334 - 118th Congress (2023-2024): Steel Modernization Act of

2024. (n.d.). Congress.gov | Library of Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118thcongress/house-bill/9334/text.

21 - Energy Communities Data page. (2024, September 20). U.S. Department of The Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/the-inflation-reduction-act-a-place-based-analysis-updates-from-q3-and-q4-2023.

22 - Text - H.R.9334 - 118th Congress (2023-2024): Steel Modernization Act of

2024. (n.d.). Congress.gov | Library of Congress. https://www.congress.gov/bill/118thcongress/house-bill/9334/text.

23 - The Inflation Reduction Act: A Place-Based Analysis, Updates from Q3 and Q4 2023. (2024, September 20). U.S. Department of The Treasury. https://home.treasury.gov/news/featured-stories/the-inflation-reduction-act-a-place-based-analysisupdates-from-q3-and-q4-2023.

24 - EXPORT-IMPORT BANK OF THE UNITED STATES. (2023). FISCAL YEAR 2023 (Q2) DEFAULT EXPERIENCE. In EXPORT-IMPORT BANK OF THE UNITED STATES DEFAULT RATE REPORT. https://img.exim.gov/s3fs-public/congressional-resources/default-report/default-report—march-2023_final-with-stress-test-addendum_508-compliant.pdf.

25 - Rorke, C., Bertelsen, G., & Climate Leadership Council. (2020). AMERICA’S

CARBON ADVANTAGE. https://clcouncil.org/reports/americas-carbon-advantage.pdf.

26 - United States Joint Economic Committee. (2024, February 8). What is a carbonborder adjustment mechanism (CBAM) and what are some legislative proposals to make one? - United States Joint Economic Committee. https://www.jec.senate.gov/public/index.cfm/democrats/2024/2/what-is-a-carbon-border-adjustmentmechanism-cbam-and-what-are-some-legislative-proposals-to-make-one.

27 - Interpretation of foreign entity of concern. (2024, May 6). Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/05/06/2024-08913/interpretation-of-foreign-entity-of-concern.

28 - Fortune-Taylor, S., Hallren, R. J., & U.S. International Trade Commission. (2022). Worker-level responses to the USMCA High Wage Labor Value Content Rules requirement. In ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES (Working Paper 2022–01–A). U.S. International Trade Commission. https://www.usitc.gov/publications/332/working_papers/worker_level_responses_fortune_taylor_and_hallren_1.7.12.pdf.