The labor market added 151,000 net jobs in February, with substantial minimal revisions to December and January. The unemployment rate ticked upwards by 0.1pp to 4.1%, with prime-age employment falling by 0.2pp to 80.5%. Wage growth reverted after shooting up last month (likely due to weather effects), and has been hovering around 4% for nearly a year. These figures are fairly close to what we previewed in our Jobs Day Forecast earlier this week (we forecasted 160,000 job gains, 4.1% unemployment, and 3.9% year-over-year wage growth).

On its face, this month’s jobs report seems fine: a labor market that is still adding jobs at a healthy clip, with high employment levels and robust wage growth. But, with all that’s taken place with tariffs and other policy developments since the reference week for the establishment and household surveys, the jobs report feels like old news already. You can think of this report as the last snapshot of the labor market before the 2025 headwinds start to hit. With hours continuing their steady decline and the composition of job growth currently supported by industries that are likely to slow later this year, the labor market risks look more skewed to the downside.

No new JOLTS data today—that comes in next week.

Real-time Growth Rates: Payroll Statistics

Sectoral Job Growth Decomposition

Hours Continue to Fall

While we generally do put too much emphasis on alternate measures of unemployment (they mostly track the headline U-3 rate), this month’s spike in the U-6 unemployment rate, the broadest measure of unemployment, caught our attention. The U-6 unemployment rate rose from 7.5% to 8.0%, and is at its highest point since October, 2021.

The reason for the jump in U-6 is mostly the increase in the number of employed workers that are part-time for “economic reasons” (the next-broadest measure of unemployment, U-5, did not spike as much and does not include these workers). These are workers who are part-time, would prefer prefer full-time work, but cannot obtain it either because they could not find a full-time job or because their hours were reduced due to slack conditions at their employer (it is not, as many people commonly take it, people who are taking part-time jobs to make ends meet, but would otherwise prefer to be non-employed).

The number of workers that are involuntarily part-time employed shot up this month. Over the latter half of last year, it looked like we might be getting relief on this front. This is a noisy measure, but the trend over the past two years is pretty evident: there has been significant labor market softening through the hours margin. If one looks at the two categories of involuntary part-time workers, we see an increase in both those who are part-time due to slack conditions and those who could only find part-time jobs.

We can also see a steady decline in full-time employment rates, and a significant decrease in February. Full-time employment is now a full percentage point below its 2019 average.

And it’s not just in the household survey, it’s in the establishment survey as well. Average weekly hours fell in the previous report (January), and many thought this was a one-off effect of wildfires and bad weather. Unfortunately, the average workweek did not rebound in February, and is the lowest it has been since the depths of the Great Recession.

To be careful here, average weekly hours are not perfectly correlated with the health of the labor market, due to composition issues. Average weekly hours declined in the late-2010s, as the labor market was tightening, and spiked in 2020. Those movements are likely composition-driven, as the tighter labor market drew in marginalized workers towards the end of the 2010s expansion, and low-hours workers were disproportionately laid off during COVID. Part of the reason for the decline in average hours since COVID is the reemployment of low-hours workers.

The rise in part-time for economic reasons and decline of full-time work suggests that the more recent decline in hours looks a lot more like slowing labor demand. The decline in hours recently has taken place as employment has moved sideways or even declined slightly, not risen. One theme throughout the “low hiring, low firing” story is that businesses are holding onto labor after experiencing difficulties filling jobs during the tight COVID labor market. That may be the case, but it may mean that labor market slack simply shows up in other places—in this case, businesses are slowing their growth in labor utilization by cutting back on the hours margin, rather than the employment margin. The question is: how long can this last before they feel the need to reduce headcount, either by slowing hiring further or looking at layoffs?

The Composition of Job Growth Continues Pose Risks

A risk that we’ve highlighted recently is the sectoral narrowing of job gains. As the labor market has slowed, most of the job gains have come from “acyclical” sectors (healthcare, education, government) with little impulse coming from “cyclical” sectors (goods-related, professional and business services) except for construction.

This month saw a slight pickup in these cyclical sectors, mostly from goods manufacturing, and our diffusion indices picked up slightly. However, the sectoral scope of job gains is still historically narrow.

If one looks into the details of where job growth is coming from, it raises a lot of doubt about whether the current trajectory of job growth can be maintained. Take manufacturing, for instance. Manufacturing posted a gain in jobs in February, but with the turmoil and uncertainty over trade policy over the past couple of weeks, more pessimism around future prospects for manufacturing activity and employment is warranted. Take, for example, some of the comments in the most recent ISM Manufacturing report:

- “Customers are pausing on new orders as a result of uncertainty regarding tariffs. There is no clear direction from the administration on how they will be implemented, so it’s harder to project how they will affect business.” [Transportation Equipment]

- “Inflation and pricing pressure continue to drive uncertainty in our 2025 outlook. We are seeing volume impacts due to pricing, with customers buying less and looking for substitution options.” [Food, Beverage & Tobacco Products]

- “New orders continue to be strong after picking up in December. The uncertainty about tariffs keeps us cautious on spending, despite the strong sales right now.” [Electrical Equipment, Appliances & Components]

- “Internal analysis ongoing about impact of tariffs, but nothing concrete yet. General business conditions remain tepid; outlook on the durables side growing more pessimistic with growing domestic inventories of automobiles.” [Plastics & Rubber Products]

- “Customer volumes seem to be better than 2024. However, customers are still very hesitant to commit to long-term volumes due to the market uncertainty caused by proposed tariffs on steel/aluminum imports.” [Primary Metals]

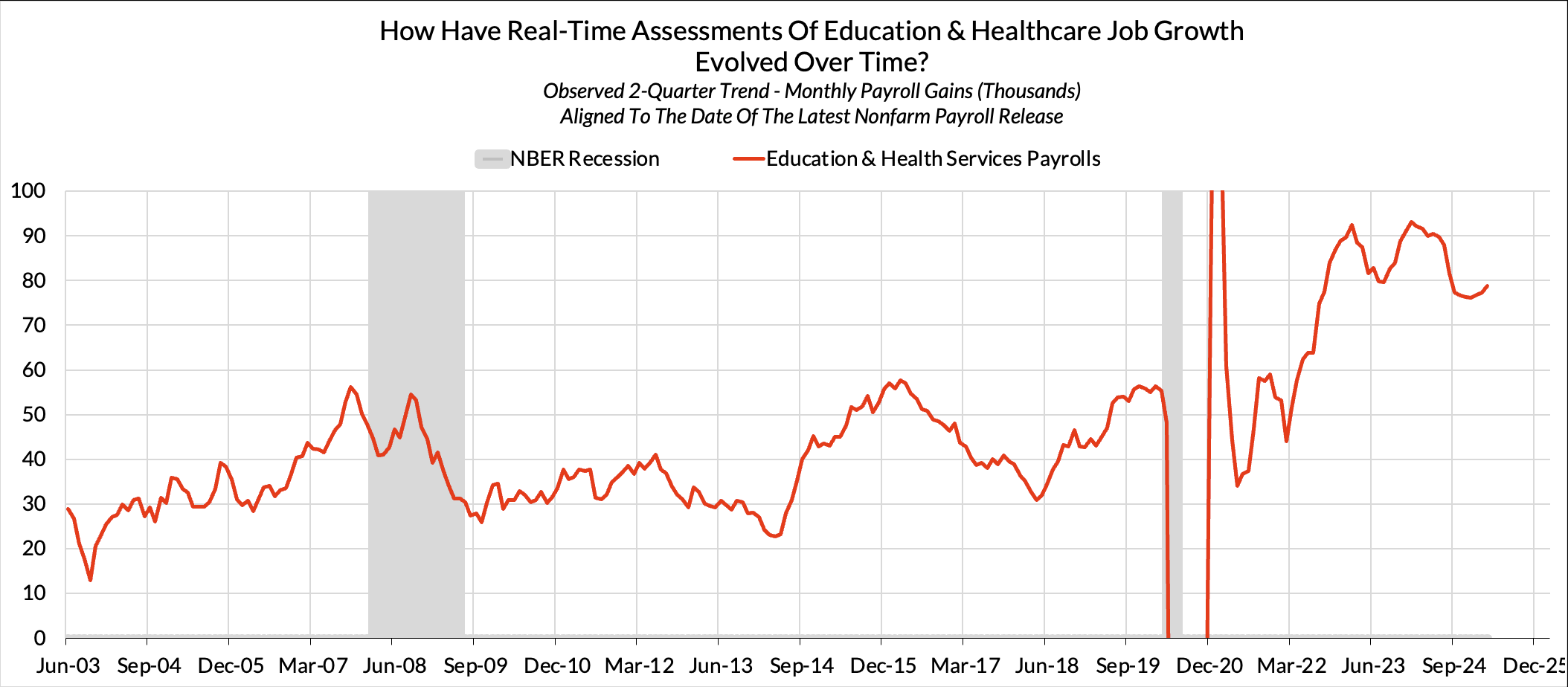

Turning to the acyclical sectors, education and health employment continues to be a strong source of job gains. Even without headwinds from reduced federal support for education, health, and research programs, job growth here was likely to slow due to dissipating “catch-up” growth, since this sector was slower to recover than others. The prospect of large cuts in federal spending on education and health programs only compounds any concerns around job growth in this sector.

Meanwhile, some other areas of job growth are faltering. Leisure and hospitality employment, which fell in January, did not rebound in February. We were hoping that January was a one-off due to weather effects, but there may be more weakness here.

Finally, government employment appeared to slow down in February. The slowdown came primarily from state and federal government, with local government still adding jobs at a strong clip. However, this report predates much of the layoffs from DOGE this month, and the outlook for further federal layoffs is extremely uncertain.

In short, the sectoral composition of job growth does not suggest a rosy outlook for the rest of the year. Cyclical and rate-sensitive industries are stymied by a Fed that is reluctant to cut rates until they are certain inflation is going to continue lower, which will be difficult due to the day-to-day variation in tariff policy. Meanwhile, job growth in acyclical industries is either slowing, outright negative, or likely to slow later this year. With that backdrop, it is difficult to tell a story where job growth continues to remain as strong as it has.

The Fed May Not have the Luxury of Being Patient

Soon after the jobs report, Powell spoke at the University of Chicago. Like many other Fed officials over the past few weeks, he urged for patience in light of tariff uncertainty:

The US economy continues to be in a good place… we do not need to be in a hurry, and are well positioned to wait for greater clarity

Jay Powell 3/7/25

The Fed’s confidence in the strength of the labor market and economic activity has led them to believe that they have ample time to react to inflation developments. Beth Hammack has said the Fed has the “luxury of being patient.” This attitude has neatly allowed them to avoid taking a stance on the effect of tariff policies in a politically charged environment.

However, if the labor market slows more than expected, they may not have the luxury of patience anymore. The full effects of tariff policy will likely take a long time to be fully recognized, and there is a real possibility that the labor market will show more concern before then. So far, the labor market has taken the slowdown in labor demand in the healthiest way possible: a reduction in hires instead of layoffs, a reduction in hours instead of bodies, and a reduction in job openings instead of employment. It remains to be seen how long we can continue like this, especially with the possibility of further headwinds later this year.