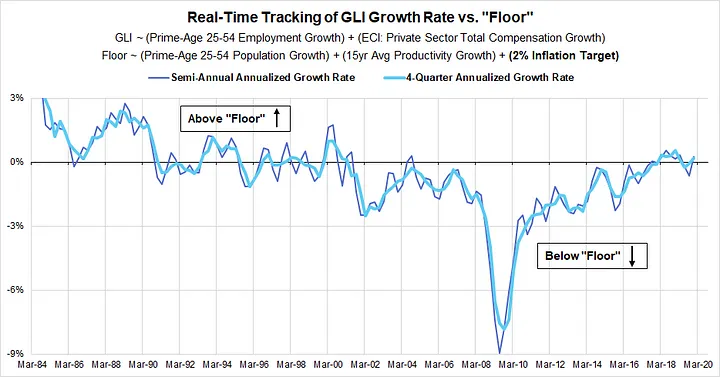

This article is intended to serve as a follow-up to the #FloorGLI proposal in “Floor It! Fixing the Fed’s Framework With Paychecks, Not Prices.”

The official national accounts estimate of gross labor income (GLI) is based on the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), but because of sharp revisions to the QCEW data, it can take several quarters before we get stable readings. The Fed does not have the luxury of waiting for such data to be fully revised before coming to its decisions. The employment data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) and the wage data from the National Compensation Survey (NCS) can offer a clearer real-time view of GLI growth and thus bypass the challenges posed by revisions to the national accounts estimate.

This post was originally published on Medium in February 2020.

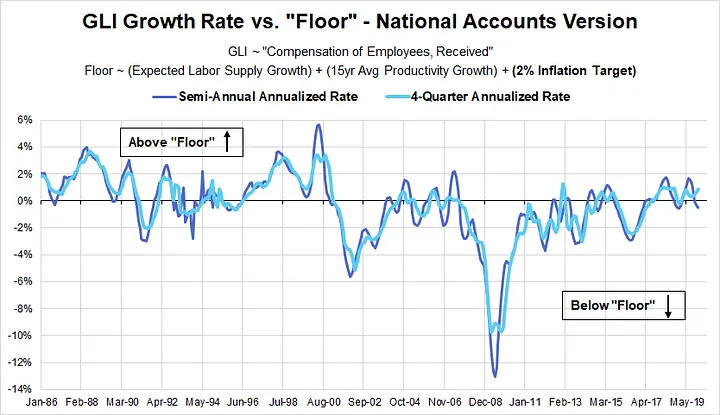

In “Floor It! Fixing the Fed’s Framework With Paychecks, Not Prices,” I used the “Compensation of Employees, Received” series from National Income & Product Accounts Table 2.6 to show how gross labor income (GLI) growth and the Fed’s projections of GLI growth had evolved over time. While the conceptual consistency of the national accounts series has some advantages, the revisions to the series can be a major problem if the series is heavily relied upon for making real-time decisions.

National accounts data, especially GLI, can be revised aggressively, often for several quarters in retrospect. This makes it more difficult to take the most recently released national accounts data at face value. What you see with respect to GDP or GLI growth for a given quarter can look very different in later releases. The Current Population Survey (CPS) and the National Compensation Survey (NCS) can help cut through this problem by giving us estimates of employment and wage growth that are not subject to the same problem of revisions.

The CPS, also known as the “household survey,” gives us fairly reliable monthly estimates of employment growth and demographic structure on ‘Jobs Friday.’ There are minor revisions to the seasonal factors of CPS estimates but the underlying source data is not subject to revision. Similarly, the employment cost index (ECI), which is derived from the NCS, also avoids the issue of revisions that stems from the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW).

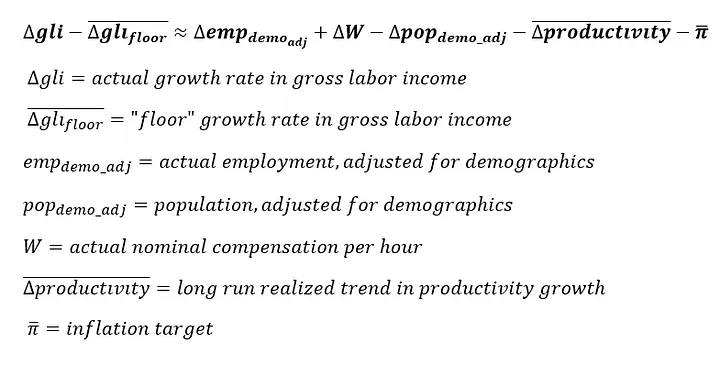

The Arithmetic Specification of Gross Labor Income (GLI)

GLI is the product of employment, compensation per hour, and the average workweek. While variations in the average workweek can matter around local time horizons, the vast majority of the variation in GLI growth reflects changes in employment and hourly wage growth. As a result, estimates of employment from the CPS and hourly wage growth from the NCS should be sufficient for developing a robust real-time tracker of GLI growth.

The Conceptual Derivation of the “Floor” Under GLI Growth

The specified “floor” for gross labor income growth can be conceptually decomposed into (1) an estimate of potential labor supply growth, (2) a baseline target for real wage growth, and (3) a baseline target for the rate of inflation.

Potential labor supply growth can be conservatively estimated from the data on population growth and demographic structure in the CPS. For a more aggressive definition of the “floor” (not specified here), labor market slack in the form of elevated unemployment and underemployment could also be taken into account. The long-term trend in productivity growth and the Fed’s 2% inflation target can be used for calibrating the other two components of the “floor” for GLI growth.

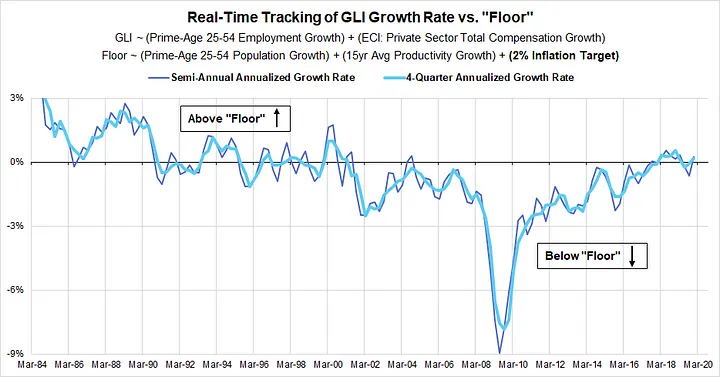

Tracking GLI Using Prime-Age 25–54 Employment and ECI

The growth rate of employment and population among prime working age adults (age 25–54) in the CPS can be used for deriving a quick estimate of how employment is growing relative to potential labor supply.

Likewise, the growth rate in ECI for compensation of private industry workers can give us a reliable real-time estimate of how wage growth is evolving relative to the long-term trend in productivity growth and the inflation target.

With these two estimates, we can derive a real-time tracker of GLI growth without having to go through the trouble of comparing revised and unrevised estimates of the “Compensation of Employees, Received” series.

How Prime-Age Employment and ECI Compare To The National Accounts

While the real-time GLI tracker has sometimes diverged from what the latest release of the “Compensation of Employees, Received” series now shows, the policy prescriptions implied by both series are generally quite similar. The lack of readily available archives for the national accounts series makes it more difficult to compare what the two series would have suggested to policymakers in real-time.

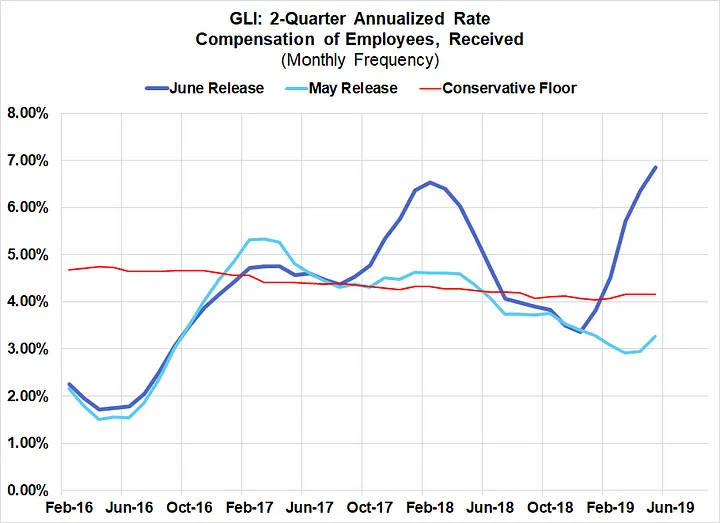

What The Real-Time GLI Tracker Has Been Telling Us Lately

In the summer of 2019, the prime-age 25–54 employment rate and the ECI for total compensation among private industry workers brought estimates of the real-time tracker of GLI growth below the conservatively defined “floor.” When coupled with the fact that financial conditions were signaling a growth outlook that hinged on Fed easing, the cuts of 2019 were probably appropriate.

Growth in ECI has yet to fully rebound, but we have seen a sharp rise in the prime-age employment rate over the past 5 months. This has helped to power the real-time GLI tracker back above the “floor.” Considering that financial conditions also suggest no major downside risks to the expected path of GLI growth, further easing does not appear necessary at this stage. Yet with core inflation continuing to run below the Fed’s 2% target, further tightening also appears to be unjustified. Until we see a clearer inflection in macroeconomic data or financial conditions, a Fed on hold remains quite reasonable.