Tariffs are back. With President Trump implementing and still proposing sweeping new import tariffs, the U.S. economy is staring down the barrel of policy-driven price increases and a new round of supply-driven cost-push inflation. If enacted for a long enough period of time, these policies could push up the prices of a wide array of goods — from raw materials like steel and lumber to consumer goods and services tied to the cost of cars and other durable goods — without any corresponding increase in consumer demand.

The Federal Reserve, however, lacks a robust strategy for dealing with this kind of inflation, which makes for messy interest rate moves and even messier policy communication. The Fed has navigated the raft of 2020-22 pandemic era supply shocks very admirably, but there are still big lessons to learn and reasons to fear the Fed will make the wrong call in a future scenario. As 2008 and 2011 should have taught us, inflation can accelerate aggressively in the short run even as nominal income and spending can decelerate further and risk more dire economic consequences in the process.

Tariffs Are Not The Textbook Inflation That Monetary Policy Is Supposed To Respond To

Not all inflation is created equal. Economists generally distinguish between inflation driven by sustained sources of demand generation and more one-off types of inflation that are typically tied to episodic economic adjustments. In the case of tariffs, they are best understood as a "one-time" input costs for producers and adversely affecting the supply side. Of course, "one-time" can mean multiple months, quarters, or even years. That a phenomenon is time-limited does not mean it will only affect a few months of data.

In theory, higher prices for imported goods can be offset by lower prices for other goods and services; nominal spending and demand could simply be reallocated. In practice? These shocks have an asymmetric inflationary effect. Prices for goods affected by tariffs will go up at the margin; don't expect price reductions elsewhere. Nevertheless, these are "one-time" price shifts that, over time, should not affect the average growth rate of prices meaningfully.

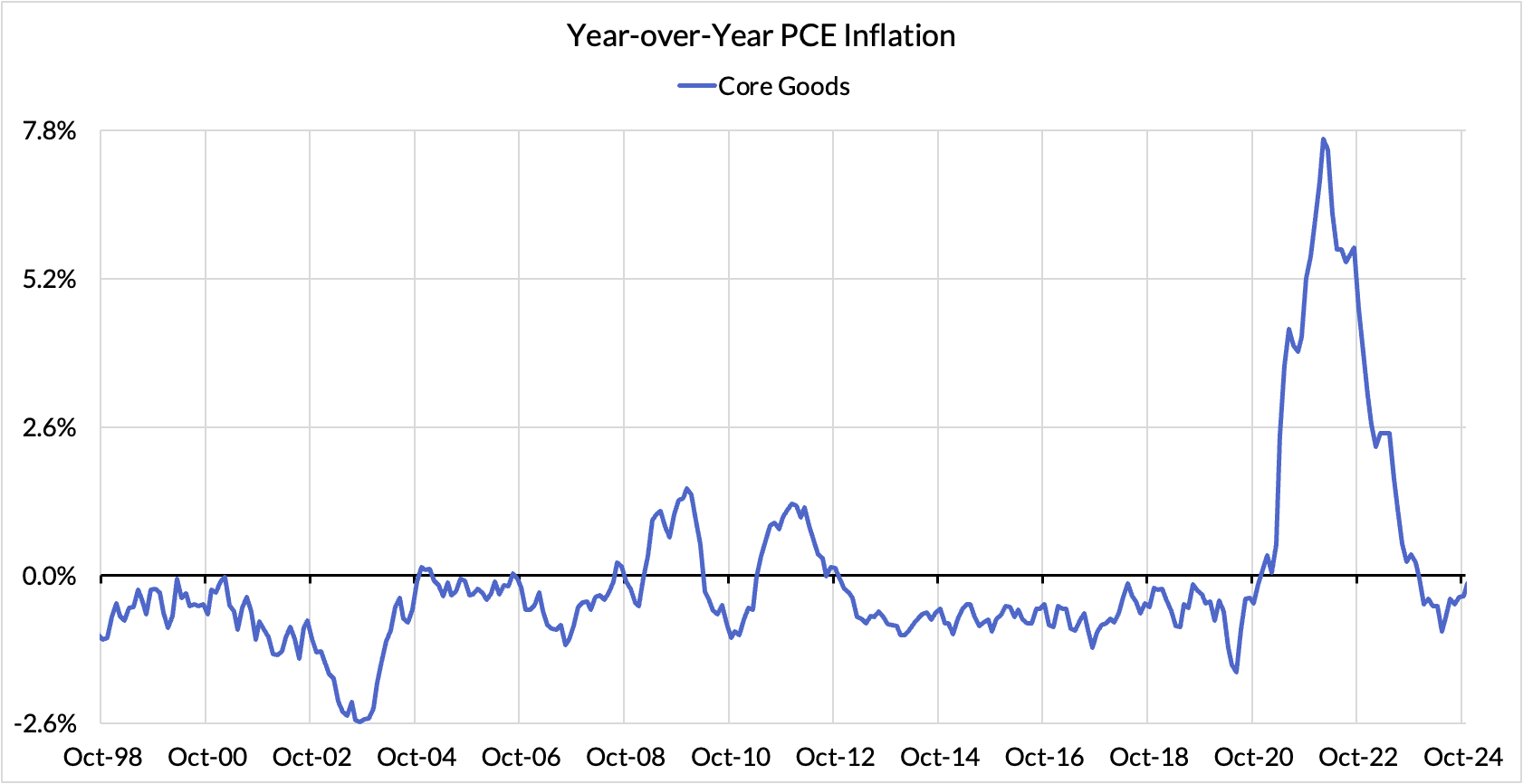

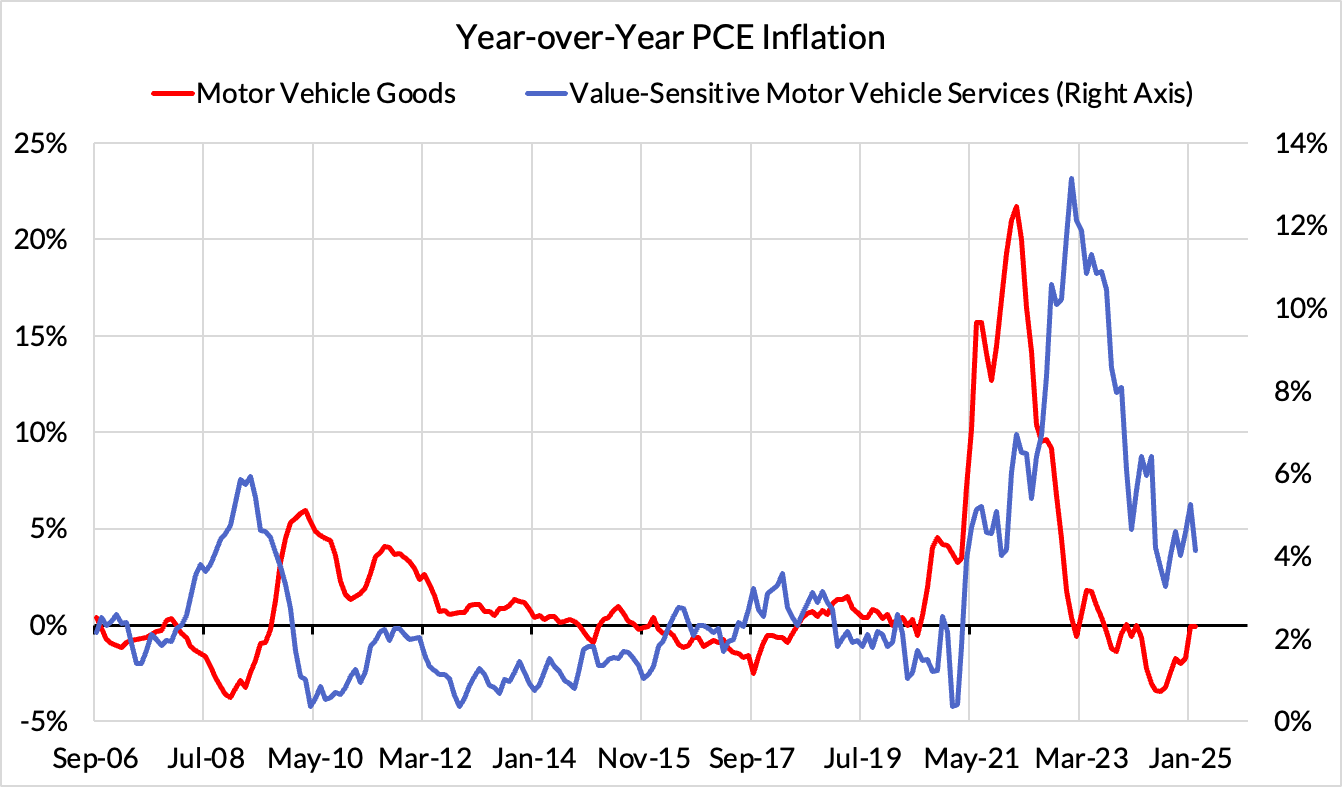

When we see sizable adverse supply shocks, we typically see a one-time increase in the price level, and not necessarily a sustained inflationary trend. These effects ripple through a range of goods and services. For example, the global shortage of microchips caused a sustained bottleneck in motor vehicle production. First used car prices began to surge, but then so too did new vehicles and parts. As the value of new and used vehicles surged, the pricing of related services also surged. Leasing, rental, repair, maintenance, and insurance of motor vehicles are technically "services," and yet their pricing is inherently tied to goods pricing dynamics, and more so than labor market dynamics.

The tariffs being proposed hit a wide range of goods and services within CPI and PCE measures of inflation and will take varying amounts of time to show up in the data. Nevertheless, treating these effects as a sign of macroeconomic overheating, and thereby warranting higher interest rates, can be a mistaken conclusion.

The Fed’s Tool Is a Hammer. Not Everything Is A Nail

The Fed's main tool — the federal funds rate — is intended to influence aggregate demand. Raising interest rates makes borrowing more expensive, slowing how businesses and households spend, whether that be on capital or labor, investment or consumption. Less consumer spending puts marginally less demand-side pressure on consumption, and thereby limits scope for price increases. Tariffs, however, do not operate through this channel. Instead, higher tariffs can push up prices even as nominal consumer spending slows.

When inflation rises, the Fed is tempted to respond reflexively with rate hikes, regardless of the cause of price increases. This is especially likely if the Fed has underestimated the scale, scope, or duration of the shock in question. After their characterization of inflation as "transitory" in 2021, the Fed was subsequently 'stopped out' of that assessement. Price increases continued to beat the Fed's expectations. More importantly, they continued to echo over a wider range of goods and services (breadth), and over a longer period of time than the Fed had ever anticipated. While there were also sources of sustained demand generation that coincided with the supply shocks at-hand, the scale, breadth, and duration of the supply shocks encouraged them to raise interest rates higher and keep them there for longer. With the benefit of hindsight, the Fed saw that those restrictive settings were not entirely appropriate and wisely began normalizing interest rates.

In an alternative demand environment, the Fed's reflexive response to inflation outperformance represents a real risk. Higher interest rates in response to tariff-driven inflation could further suppress investment in critically undersupplied sectors, like housing and energy. At the same time, it would also slow employment and incomes, all while consumer prices are liable to crunch households' real incomes directly. Real incomes would contract further as a result, while reduced investment could exacerbate supply-side challenges. Tightening policy and financial conditions into a supply shock may be fine when it coincides with robust demand conditions, like we saw from 2021 through early 2023. In more normal or tepid demand conditions, the likelihood of adverse consequences looms larger.

The Long-Term Is Just a Bunch of Short-Terms

The Fed often tries to "look through" temporary price shocks, insisting that it targets medium and longer run inflation and can look past month-to-month volatility. But in practice, it has struggled to maintain that discipline. How do we know when volatile short term inflationary moves are the result of a time-limited one-off economic adjustment or something sustained that warrants a policy response? As each new data point comes in, markets and the Fed itself are likely to have trouble distinguishing between the two. Everyone's got a plan until they get punched in the mouth.

The announced and proposed tariffs will not be digested instantaneously. Firms comfortable with a prior policy regime will need time to fully adjust how they price products and services. Yet without a clear framework for communicating how they evaluate one-time relative price shifts from generalized overheating, the Fed risks stoking adverse feedback loops. Short-term cost shocks that exceed the Fed's expectations provoke rate hikes, which in turn weigh on households and businesses that are already likely to face income, investment, and cost pressures.

Echoes of 2008

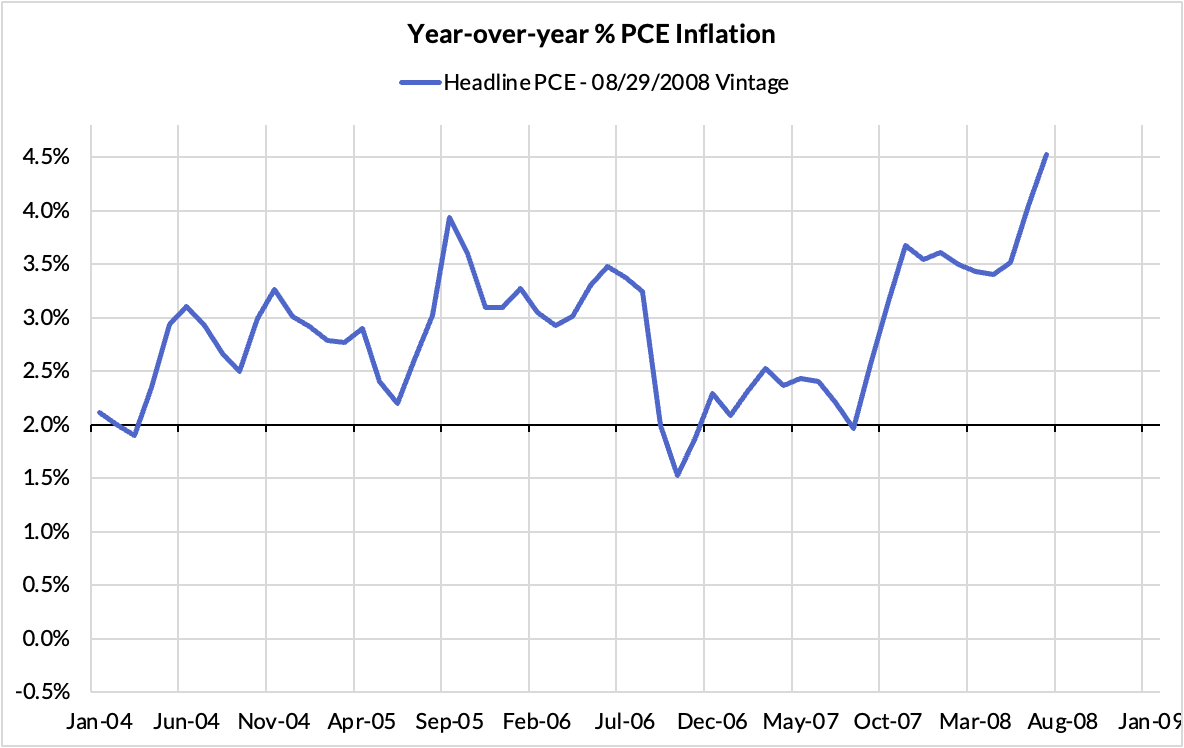

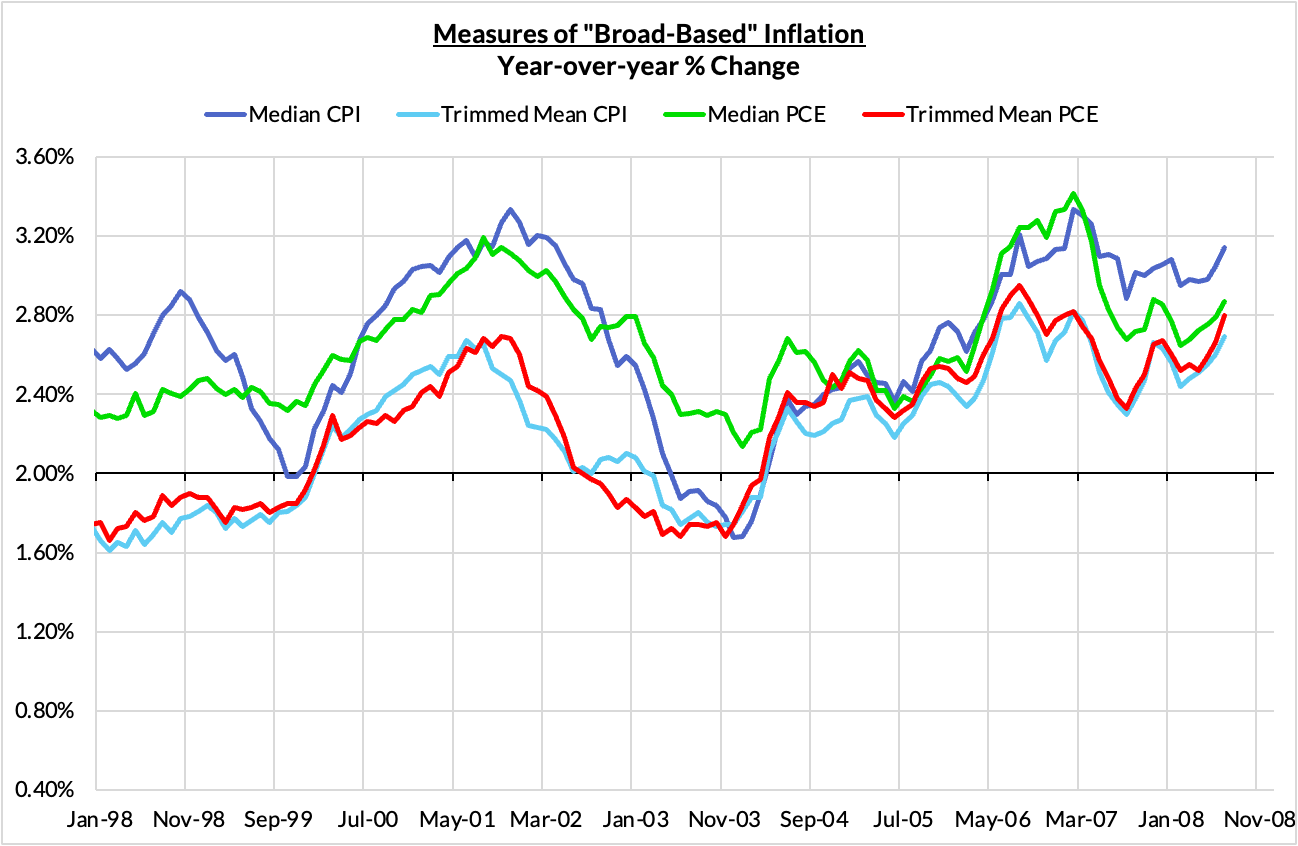

The warnings about tightening excessively into a supply shock sound ominous for good reason. Throughout the mid-2000s, inflation generally ran hotter than the Fed's (then-implicit) 2% inflation target for a sustained period. That was in large part due the boom in energy and commodity prices as a result of record Chinese and global growth. In 2008, oil prices spiked to over $145 per barrel, causing both headline inflation to surpass 4.5%, historically high even in the context of generally above-target headline inflation.

It wasn't just direct commodity price effects to gasoline and food that drove above-target inflation. The commodity price effects also helped push up prices for non-food and non-energy consumer items, many of which grew as a result of higher energy input costs.

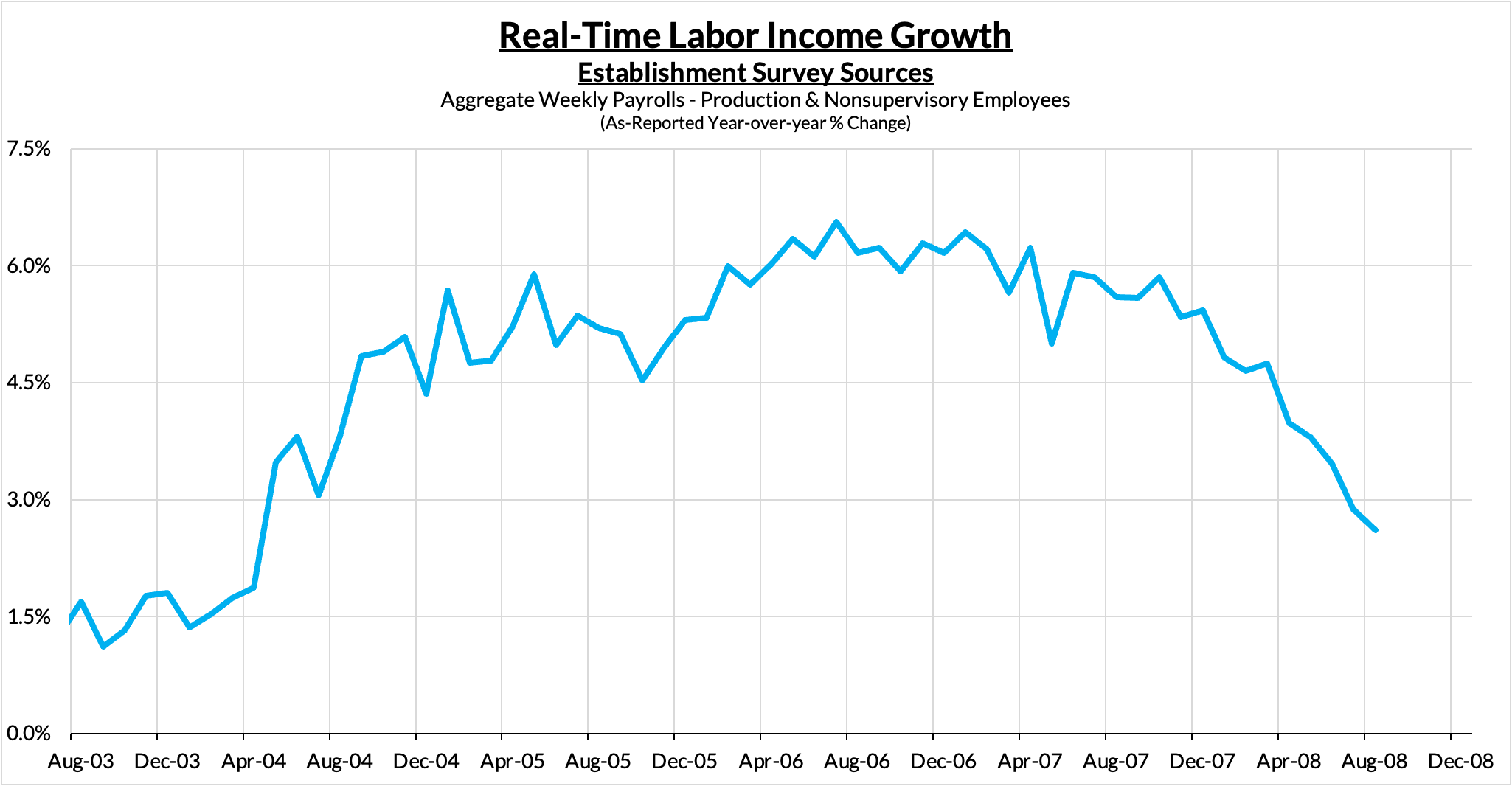

It's important to note that while inflation was running firm, other nominal measures of aggregate economic activity were clearly slowing and deteriorating. The labor market and the trajectory of household incomes were visibly in freefall throughout the summer of 2008.

Nevertheless, firms felt pressured by input cost pressures to raise the prices of airfares, food, housing, and other categories where energy was a key input. Inflation outperformed the Fed's forecasts for much of the mid-2000s, lasting longer than was previously anticipated, and was bleeding into a wider range of goods and services. Idiosyncratic supply-driven inflation was morphing into "broad-based" inflation that risked deanchoring inflation expectations. Sound familiar?

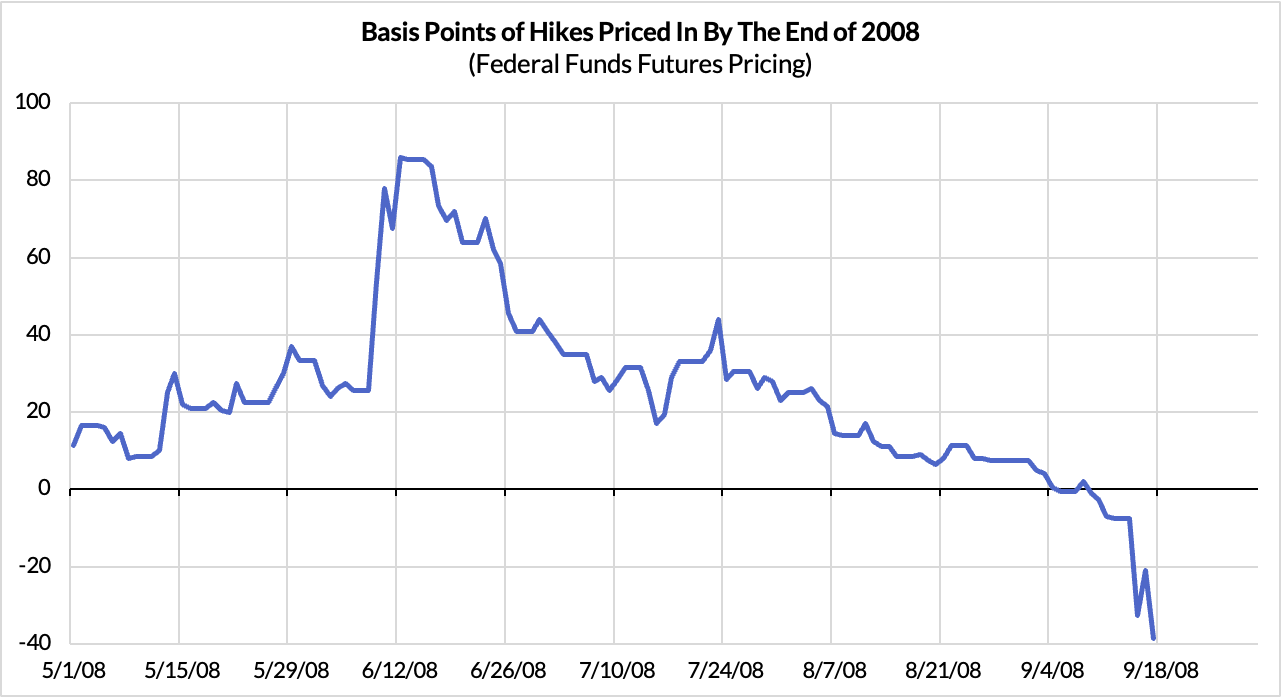

While the Fed, unlike the European Central Bank, avoided the infamy of hiking in 2008, it's not as if the Fed wasn't tempted. In the summer of 2008, senior Fed officials already sent out signals to market participants to start expecting hikes later in the year to tame inflation. On June 10, 2008, the Wall Street Journal ran with the headline “Bernanke Unshaken by Jobless Rise”

“ The risk that the economy has entered a substantial downturn appears to have diminished over the past month or so” — Chair Bernanke

“Containing the risks in what is globally a less benign inflation environment is going to probably require tighter monetary policy on average around the world” — New York Fed President Tim Geithner

Market pricing soon reflected the fact that the Fed would soon be hiking, which effectively tightened financial conditions further...just as the financial crisis was about to go from bad to worse.

The inflation of 2008 turned out to be shorter lived. As the demand dynamics of the Global Financial Crisis and Great Recession swelled further and swamped the inflationary supply shocks of that period, inflation ultimately fell markedly in late 2008 and 2009. But by that time, the damage was also done. The Fed's reluctance to cut rates more aggressively arguably deepened the Great Recession, as they passed up on a critical moment to cut rates after Lehman Brothers failed. It's a mistake the Fed cannot afford to make again.

Tariff inflation will look different but there are lessons. We are likely to see some volatile prices move sharply at first, but the scope for these policies to hit a broad set of inflation components for an extended period of time is substantial. The scope for policy and financial conditions to tighten is not hard to imagine. And yet we can also see how the recently announced tariffs might simultaneously put more aggressive pressure on employment, nominal incomes, and consumer spending. The Fed's 2025 Framework Review is an opportune time to codify the right lessons and communicate them to the public.

Conclusion: A Data-Driven Strategy For Maintaining A Steadier Hand

Tariff inflation poses a real policy and communication challenge for the Fed. Without a framework and strategy robust to adverse supply shocks, the central bank risks confusing price level adjustments for persistent inflation and tightening policy too aggressively into a slowdown.

The Fed seems unlikely to make revolutionary changes to their framework in the current moment. Switching out the 2% PCE inflation target for a nominal aggregate target, like Gross Labor Income or Nominal GDP, is likely too ambitious for Fed officials' taste. Yet they need to start developing a more rigorous strategy to communicating their interest rate outlook in response to volatile and diverging macroeconomic data.

A communication approach that formally embraces a role for nominal aggregates could help the Fed achieve 2% inflation over the longer run, and communicate accordingly. Formally acknowledging that nominal aggregates are used to disentangle supply- and demand-driven sources for inflation would be simple but meaningful shift. Chair Bernanke and President Geithner could have done much good in the summer of 2008 by pointing market participants to the ongoing deceleration in gross labor income, nominal consumer spending and nominal GDP. It may not have been a panacea, but it could have given more clarity and confidence to the public and financial markets. Financial conditions would have been more accommodative and the effects of the financial crisis would not have been as brutal.

As the risks of stagflation mount, the Fed's hand is growing unenviable. It will be difficult to carefully balance their Congressionally mandated objectives for maximum employment and stable prices over the short and longer run. They can easily be scapegoated by some elected official or political interest for doing too little on either side of their mandate.

To navigate their tradeoffs better, the Fed can develop better methods for communicating to the public when inflation likely reflects excess demand, and when it reflects cost-driven supply shocks. These methods can allow for more measured responses — and help avoid the kind of overreactions that can push the economy off course. If it does not, we will be left with the same messy communication and policy choices that add to a macroeconomic backdrop already rife with so much risk.