Today's data largely confirmed what we've known for some time now: the Fed's restrictive policies are restricting the level and growth of homebuilding activity in the US economy. But when we think holistically about the relevance of homebuilding to price stability, the restrictive effects of Fed policy extend beyond demand. They also curtail the outlook for future supply and stoke future price stability risk in the process.

While most Fed discussions of supply-side dynamics are in the context of disentangling realized inflation, less attention is given to how interest-rate-sensitive the supply side might be at any point in time (see Drechsler, Savov, Schnabl). In discussions that center on the Fed responding only to demand-side inflation, it's taken for granted that the Fed primarily or exclusively shapes demand-side outcomes. Reality is murkier.

The most inflation-relevant segments of the supply-side can vary over time, and so too can the favored financial structures for investing in capacity to address those segments. At least as it pertains to housing, which still drives most of the overshoot of the Fed's 2% inflation target, the stance of Fed policy and the level of financing costs matter, substantially.

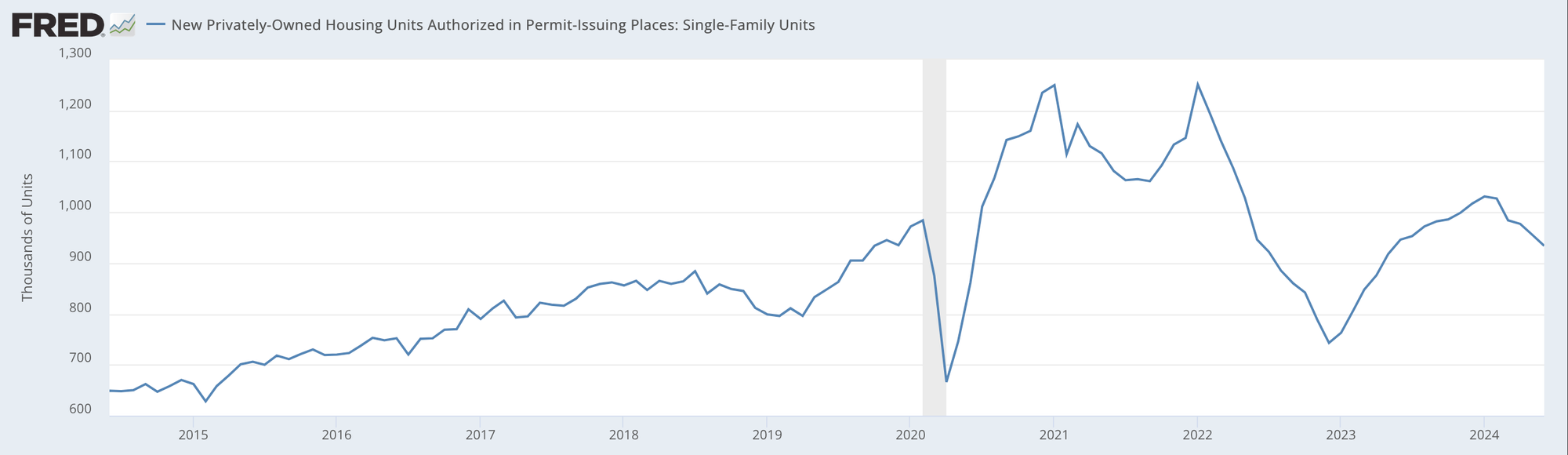

Right now we're seeing reasonably broad slowing in permitting activity tied to housing. Single-family units tend to be the most relevant than multi-family on a dollar-weighted basis, come with lower time-to-build, and are less noisy to observe month-to-month. While there are local spots of strength and weakness, permits are substantially lower than their trajectory and level at the time the Fed began embarking on rate hikes in early 2022.

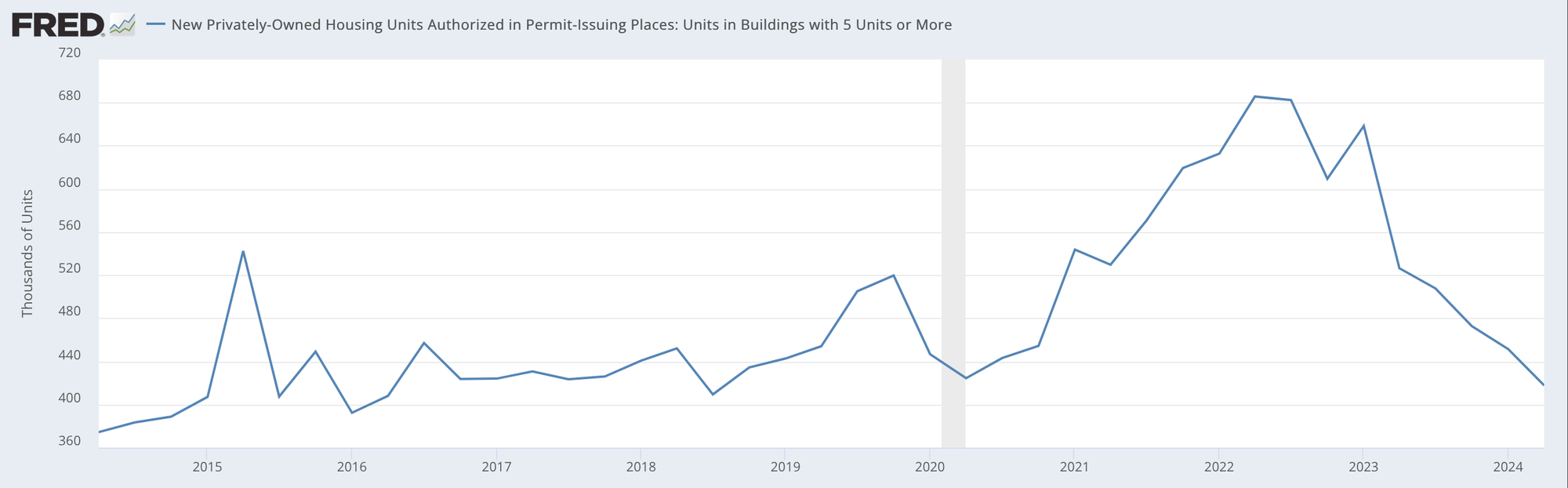

Multifamily permits are noisier but are more relevant to what the rental supply picture looks like over time (single family rentals are a growing share of the tenant occupied housing stock but still represent a minority). Looking at quarterly averages, we see a similar picture, with permitted units in yet-to-be-built multifamily buildings also falling after the Fed began raising rates and financing costs since the beginning of 2022.

It's worth noting that there is a substantially longer time-to-build associated with the average and median multifamily building project, taking at least over a year if not two or three from the time of permit to the time of completion and delivery.

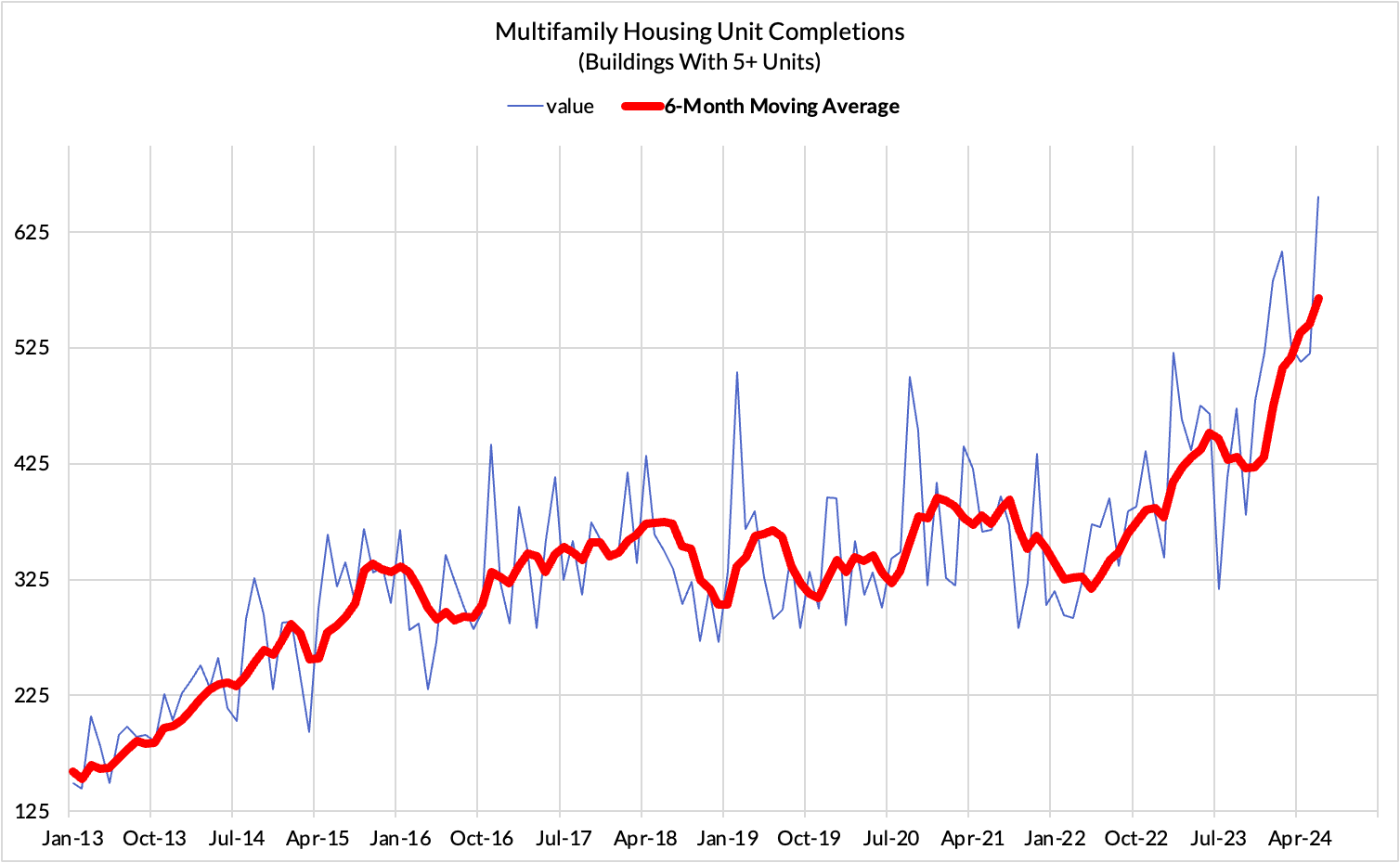

It's with this insight that we can unpack a really important point: much of the housing inflation relief we're seeing today is ironically the result of the surge in multifamily permitting and building activity that largely preceded the Fed's hiking cycle.

We continue to hit new highs in the completion of multifamily housing units. Those are units that are being delivered to the market and helping to deliver inflationary relief from the supply-side.

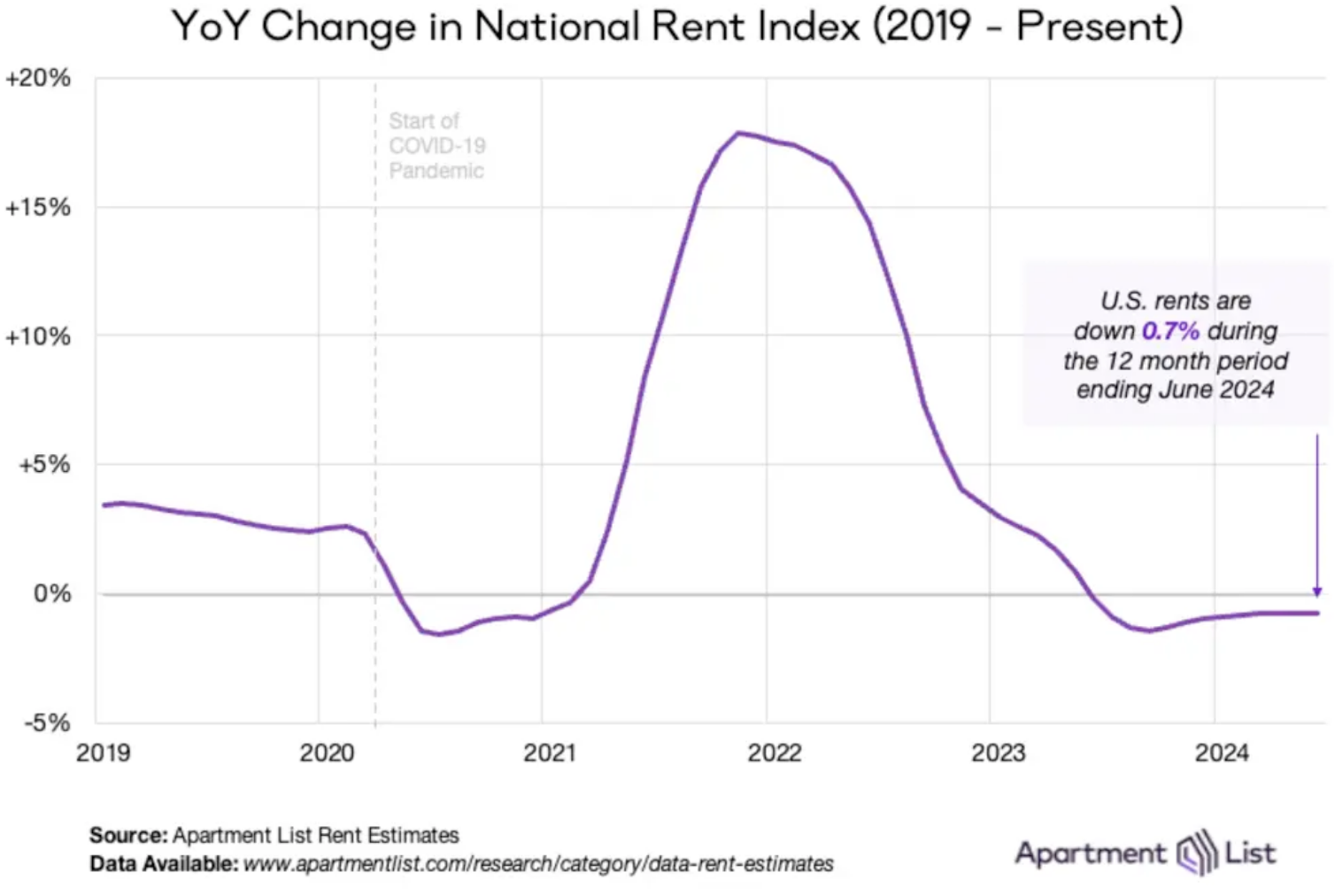

Estimates of market rent for apartments and generally have seen a substantial slowing. Due to methodological lags in the official CPI estimates, we are only now beginning to see this market rent disinflation translate into the Fed's main inflation gauges.

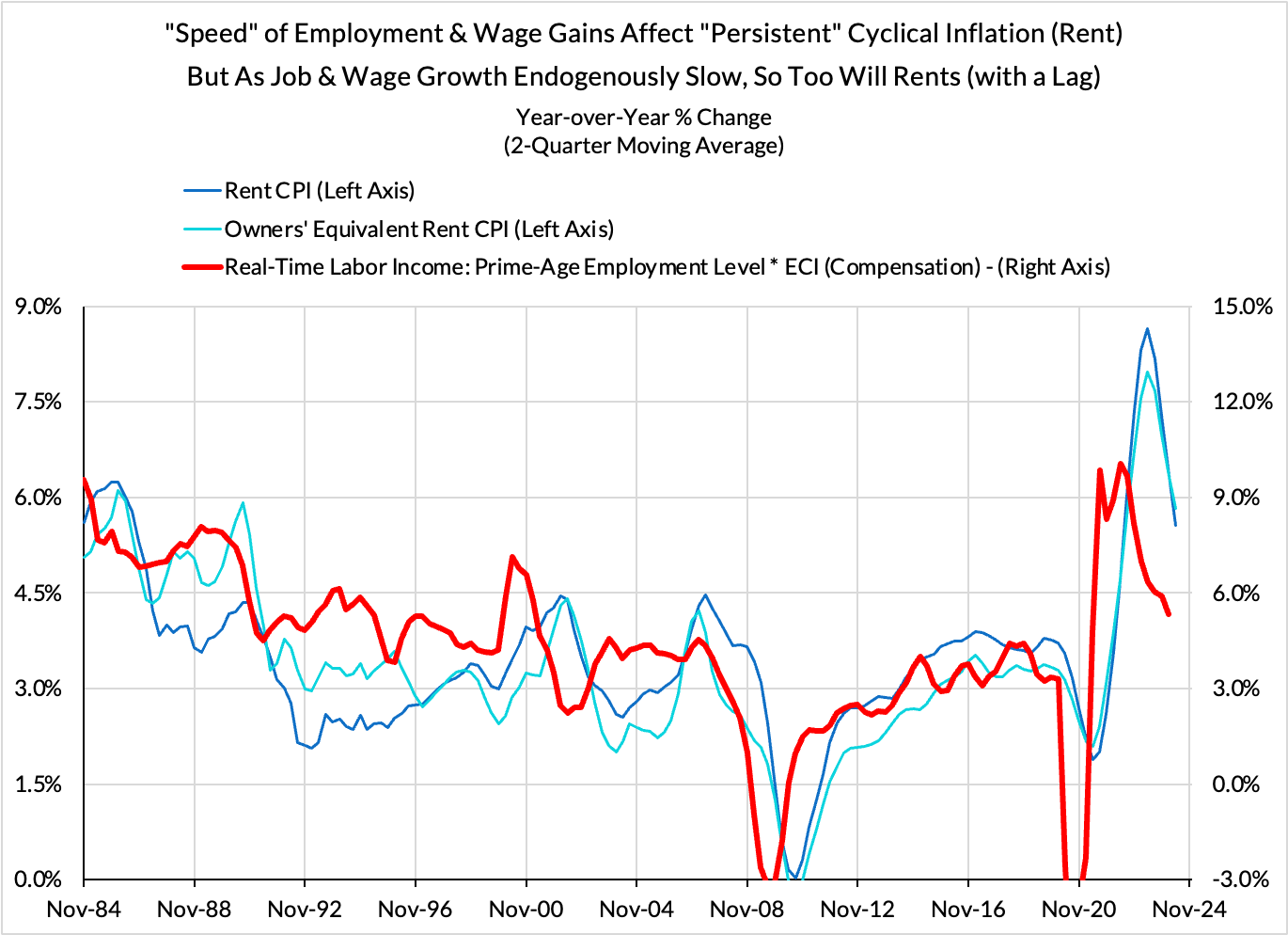

Much of the market rent slowing is also attributable to a cooling of demand through the labor market. After all, while housing supply shortages are substantially structural in the U.S., the local variation of inflation is more directly attributable to net job growth and wage growth.

Landlords can charge more when they expect there to be more renters and when there is more income available from a given renter. But these dynamics do not exist in a vacuum, independent of supply-side forces. In the current market, apartments are being delivered at a record pace and a thicker, more competitive market can clearly help check pricing power.

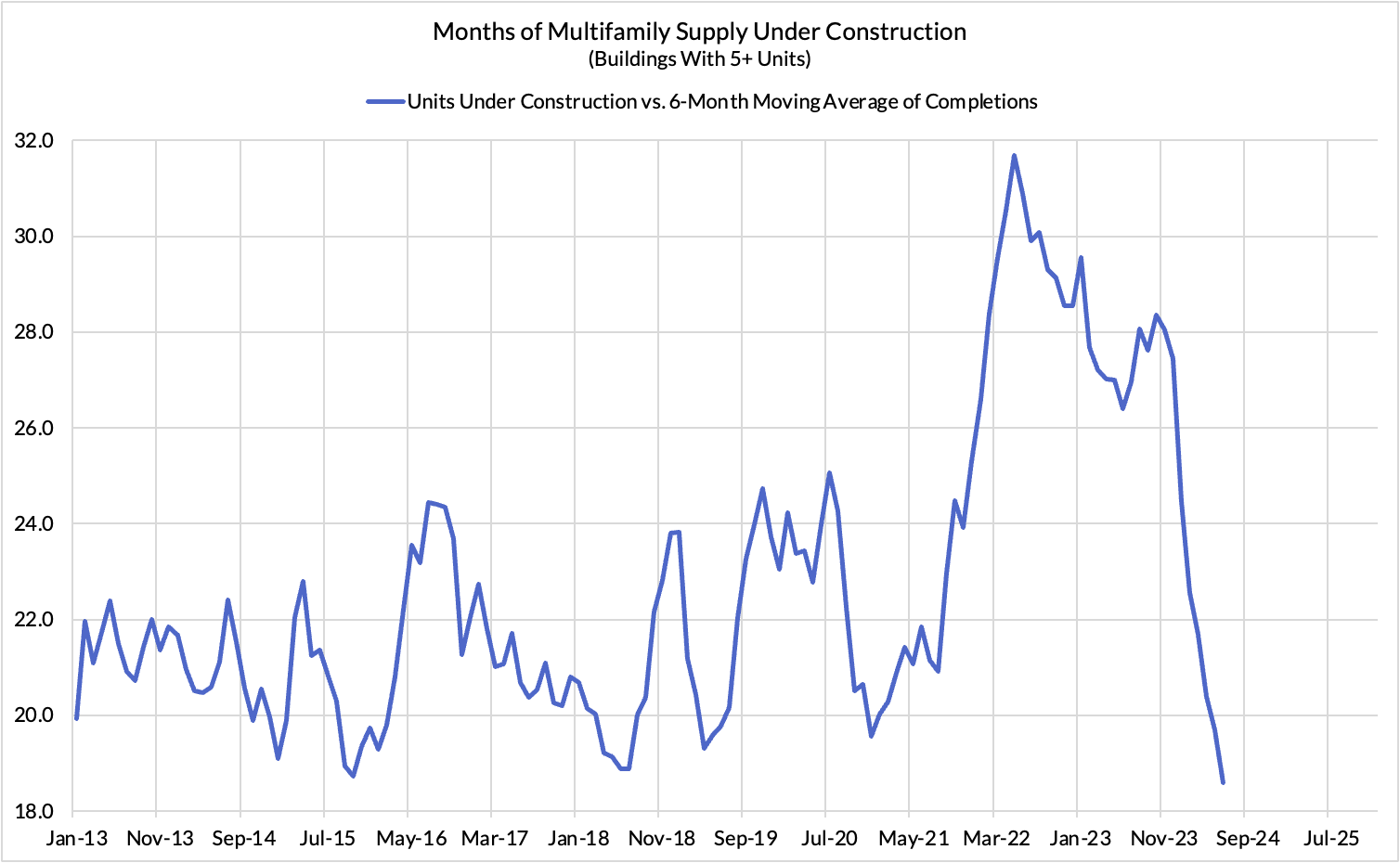

The trouble going forward, and specifically for the Fed, is that the rental supply picture does not look so rosy from here.

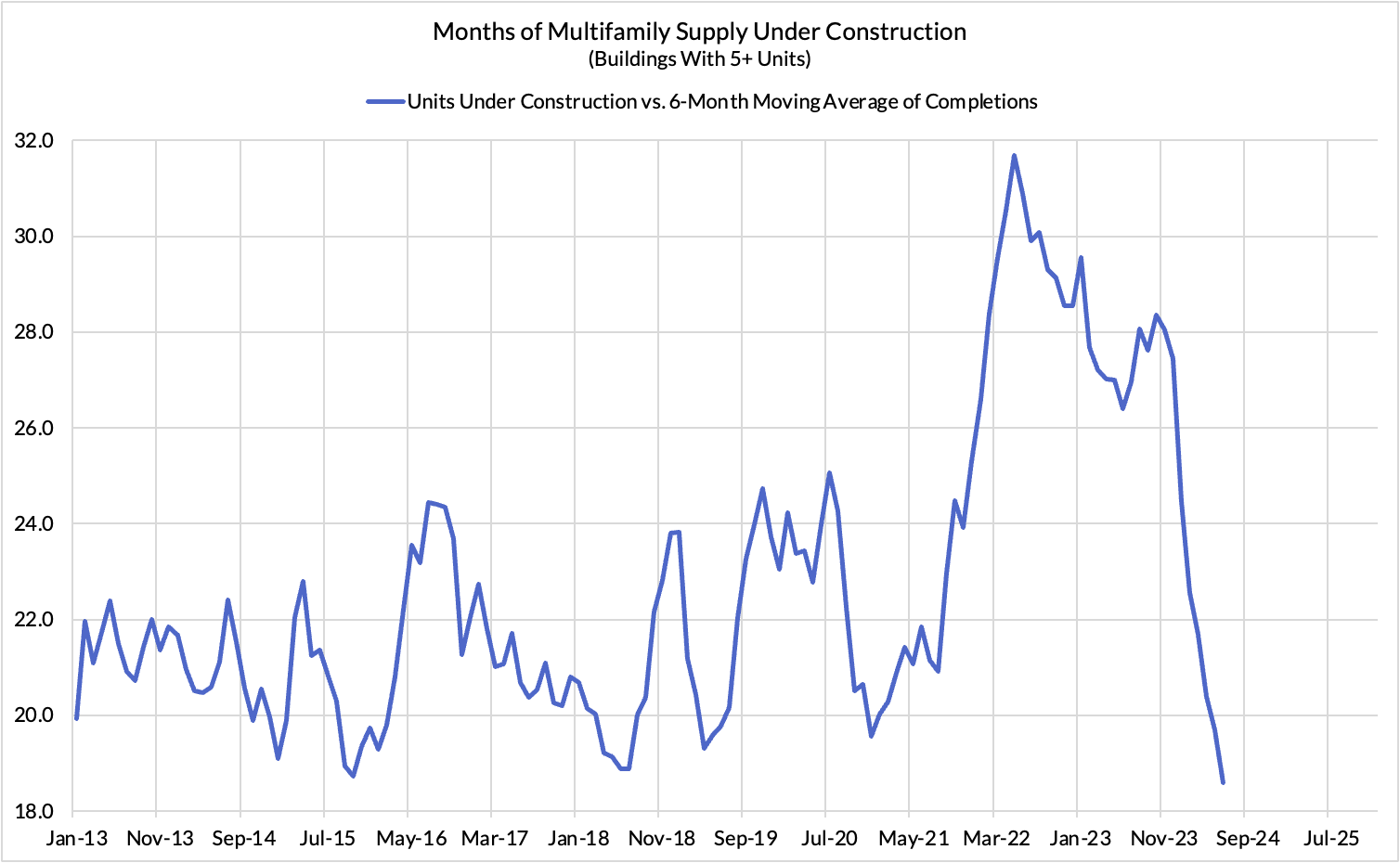

The months of multifamily units' supply under construction has fallen from over 30 months down to just over 18 months. The effect of ever-decreasing permitted units over the past several quarters is not seen in current completions. It's seen in completions 1-3 years later, but seen in lower units under construction today.

Should the supply picture show further deterioration—as measured by the number of units under construction relative to the existing capacity to complete units—upside risks to housing CPI and PCE inflation would swell. These housing inflation measures are based on rent data, even when used to proxy owners' equivalent rent.

All of this puts the Fed in a highly awkward position, one in which there aggressively restrictive policies of today have choked off future housing supply and stoked upside risks to housing inflation 1-3 years forward.

Thus the causal mechanisms we tend to harp on are growing no less relevant to how the Fed conducts policy from here. The Fed has a Congressional mandate to pursue maximum employment alongside stable prices, but the policy tools are not of reliable effect on stabilizing prices. And in some substantial instances, their intention to stabilize prices in the here and now...can instead stoke further instability in the future.

When considering the path to normalization from the Fed's current policy stance, it'll be essential to take a richer view of the policy tradeoffs the Fed faces.