In his speech at the Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, Powell was clear about his intention to prevent the labor market from deteriorating further: “We do not seek or welcome further cooling in labor market conditions.” His remarks arrived after months of a steady cooling in the labor market, marked by a fall in hiring rates, quit rates, wage growth, and a rise in the unemployment rate. The labor market, in our view, has more than rebalanced, and any more slowing unduly elevates the risk of a recession.

Now that the Fed has set out the goal of maintaining the health of the labor market, how can demonstrate that they're serious about trying to achieve that goal? We will be hoping for two things at the September meeting this week: a 50 bps cut and minimal upwards revisions to the unemployment rate projections in the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP).

In our FOMC preview last week, I wrote that our expected as well as our preferred policy choice this week is a 50 bps point cut. While some believe that the decision between a 25 or 50 bps cut isn’t that important, we think it is. A large cut up front signals that the Fed is serious about getting ahead of labor market deterioration, while a 25 bps cut and a promise to go faster if things look worse shows that they’re going to be reactive, not proactive, against further cooling in the labor market. If the Fed waits for layoffs to rise, they will probably be too late; fire prevention is more effective than fire fighting.

A common argument for a smaller cut is that in recent history, a cut larger than 25 bps is unheard of outside of a recession or financial crisis. Given that history and the absence of a recession today, why go for 50 bps on Wednesday? Implicit in this argument is the assumption that Fed actions in the past were optimal, but just because the Fed has acted a certain way in the past doesn’t mean they should act that way in the present. The Fed has often responded too late to recessions, such as in 2001 and 2008. In fact, the unprecedented nature of a 50 bps cut like this presents an opportunity for the Fed to show they’re committed to avoiding the mistakes of the past.

Another way the FOMC can communicate their commitment towards maintaining full employment is through the SEP for unemployment. The “dots” are partly an exercise in forecasting on the part of FOMC members, but also partly a statement of intent. The latter is especially true for the “long-run” estimates of economic variables, which are each member’s “assessment of the value to which each variable would be expected to converge, over time, under appropriate monetary policy.” [emphasis added]

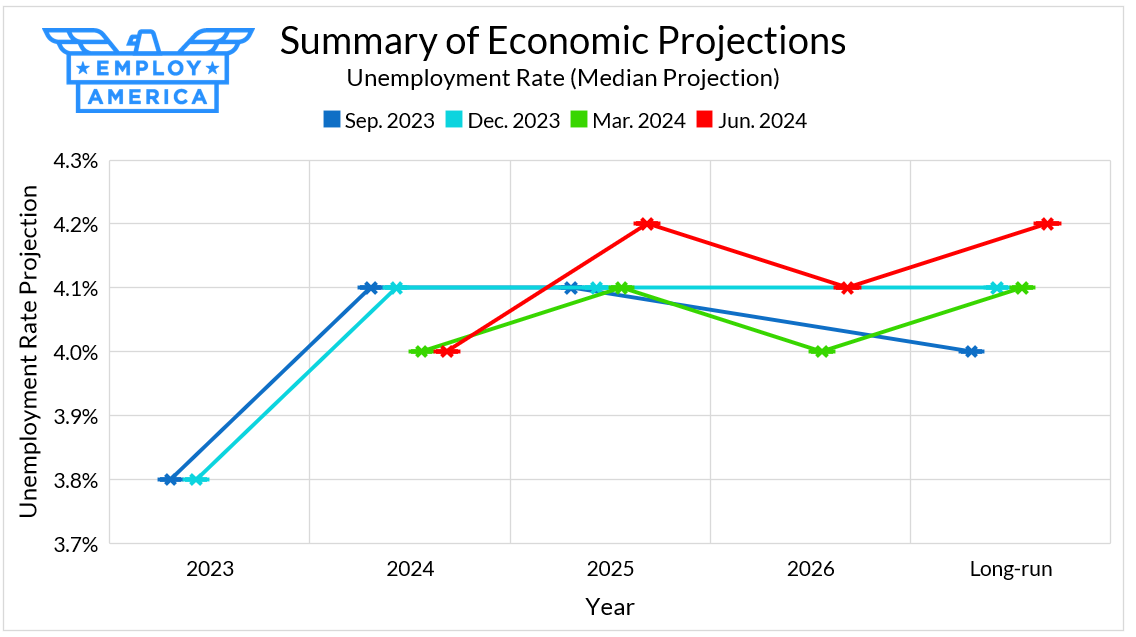

Given the rise in the unemployment rate that we’ve already experienced, the FOMC will likely revise their 2024 and 2025 unemployment rate projections upwards. By how much remains to be seen, but all else equal, the more benign the unemployment path in the SEP, the stronger the commitment to full employment. A higher unemployment path would raise the bar for reacting more strongly against labor market risk.

Turning to the long-run unemployment rate, every meeting we’ve seen a handful of members revise their estimate upwards. The median long-run estimate has quietly risen from 4.0% last September, to 4.1% in December and 4.2% in June. One member now even sees the long-run estimate as high as 4.4 - 4.5%. This looks suspiciously like moving the goalposts on full employment—it’s not that the labor market is looking worse, it’s that 4.0% unemployment is too tight! FOMC members have repeatedly written off the recent rise in the unemployment rate as the result of a recent rise in labor supply, particularly from immigration, but there’s unclear why that should change the long-run unemployment rate projection.

For all the Fed’s talk about the importance of inflation expectations, little attention has been paid to the importance of “unemployment expectations.” As I wrote in The Dream of the 90s, expectations of full employment are important to business investment and hiring decisions because demand is primarily fueled by labor income. Powell’s Jackson Hole speech can be viewed as an attempt to be explicit about setting unemployment expectations, but the Committee’s actions on Wednesday will demonstrate the extent of their commitment to full employment.