The American economy emerged from the pandemic recession with full employment, strong GDP growth, and the beginnings of a productivity boom. The right policy decisions resulted in a strong recovery and began to lay the foundations for another era of sustained productivity growth, similar to the 1990s. Sadly, in 2025, new policies are actively working against the macroeconomic conditions that are necessary to achieve that dream.

In “The Dream of the 90’s”, I examined how the macroeconomic context of the late-1990s supported strong productivity growth. I argued that productivity growth (output per hour of labor input) relied on three macroeconomic pillars: full employment, fixed investment, and supply-side stability. Full employment promoted the reallocation of labor towards higher-productivity jobs and strong labor income growth, which incentivized investment in capital and technology. Strong fixed investment in computers and research and development contributed directly to growth while improving the productivity of sectors across the economy. A stable supply-side kept inflation at bay and allowed the Federal Reserve to ease financial conditions, which helped support full employment and investment.

The confluence of those three macroeconomic conditions all support rapid productivity growth. Getting this right is critical because productivity growth is key to increasing wages and living standards over time.

In the finale to the series, I turned to the economy in the present (writing then in early 2024). Could we once again see a stretch of strong and sustained productivity growth? I was optimistic back then, arguing that the ingredients for a return to the miracle of the late-90s economy were there, but it would require the right policy moves to ensure that the three macroeconomic supports for productivity growth were present. The most recent data for 2024 showed signs of a nascent boom. Barely six months ago, The Economist described the US Economy as "the envy of the world."

It is now just over a year since we published “The Dream of the 90’s.” Unfortunately, the path to a return to the macroeconomic success of the 1990s—and all the benefits it delivered—has since rapidly narrowed. In 2025, policy is moving in the wrong direction for each of the three key macroeconomic themes.

Full Employment Under Threat

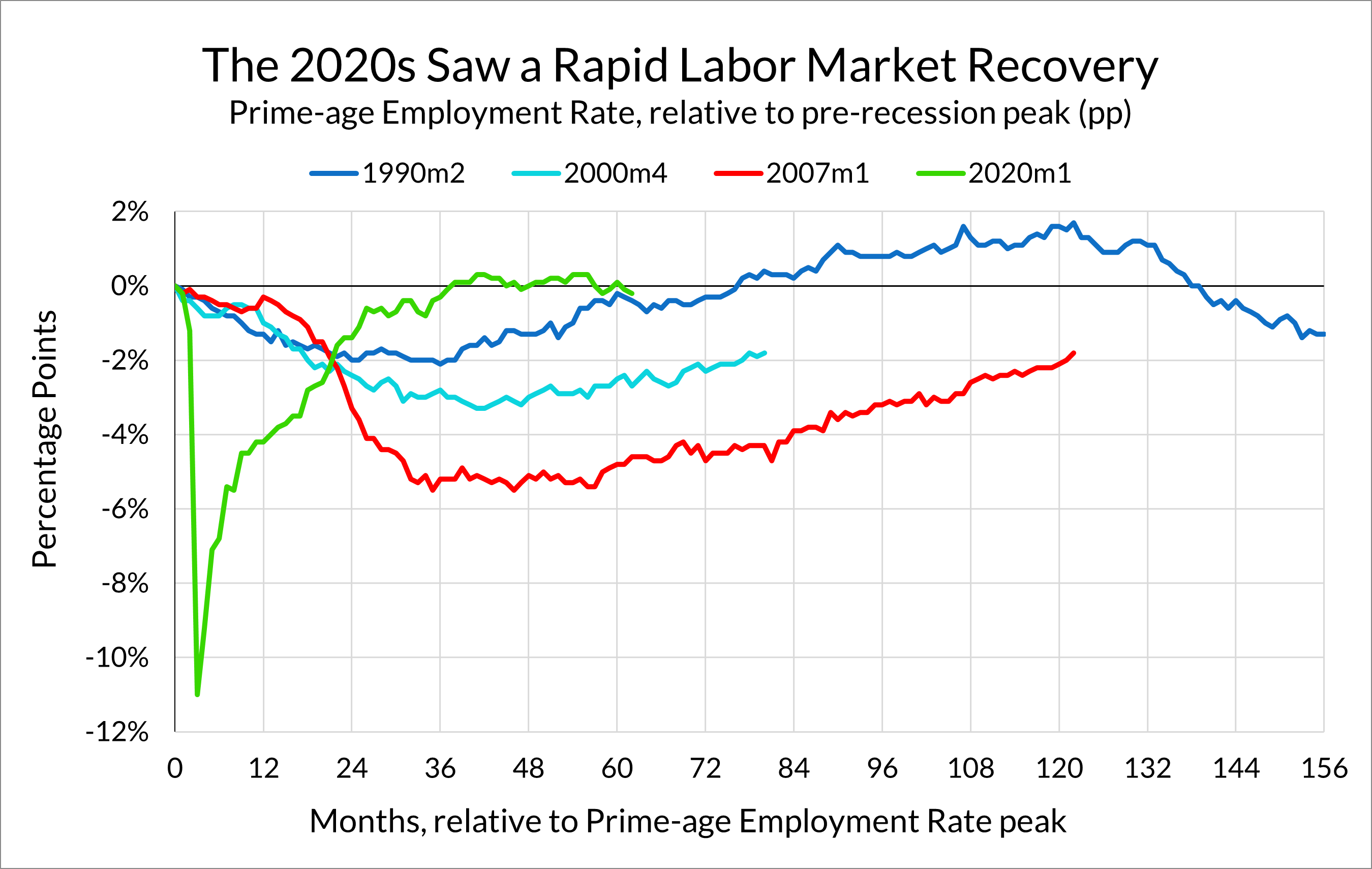

Coming out of the recession in 2020, monetary and fiscal policymakers alike were determined to avoid another slow, grinding, jobless recovery in the labor market. The result was the fastest rebound in employment following a recession in American history.

The labor market coming into 2025 was by no means perfect. The labor market had softened considerably during the preceding couple of years. Labor market dynamism in particular was looking tepid, with voluntary quit rates falling to early-2010s levels.

Still, the labor market was in historically good shape. With the unemployment rate just above 4% and prime-age employment rates near historic highs, Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago President Austan Goolsbee described the labor market as "settling into full employment.” Nominal wage growth hovered around 4%, above pre-pandemic levels. Even if quit rates were low, we had still seen a few years of rapid reallocation of workers towards higher-paying, higher-productivity occupations.

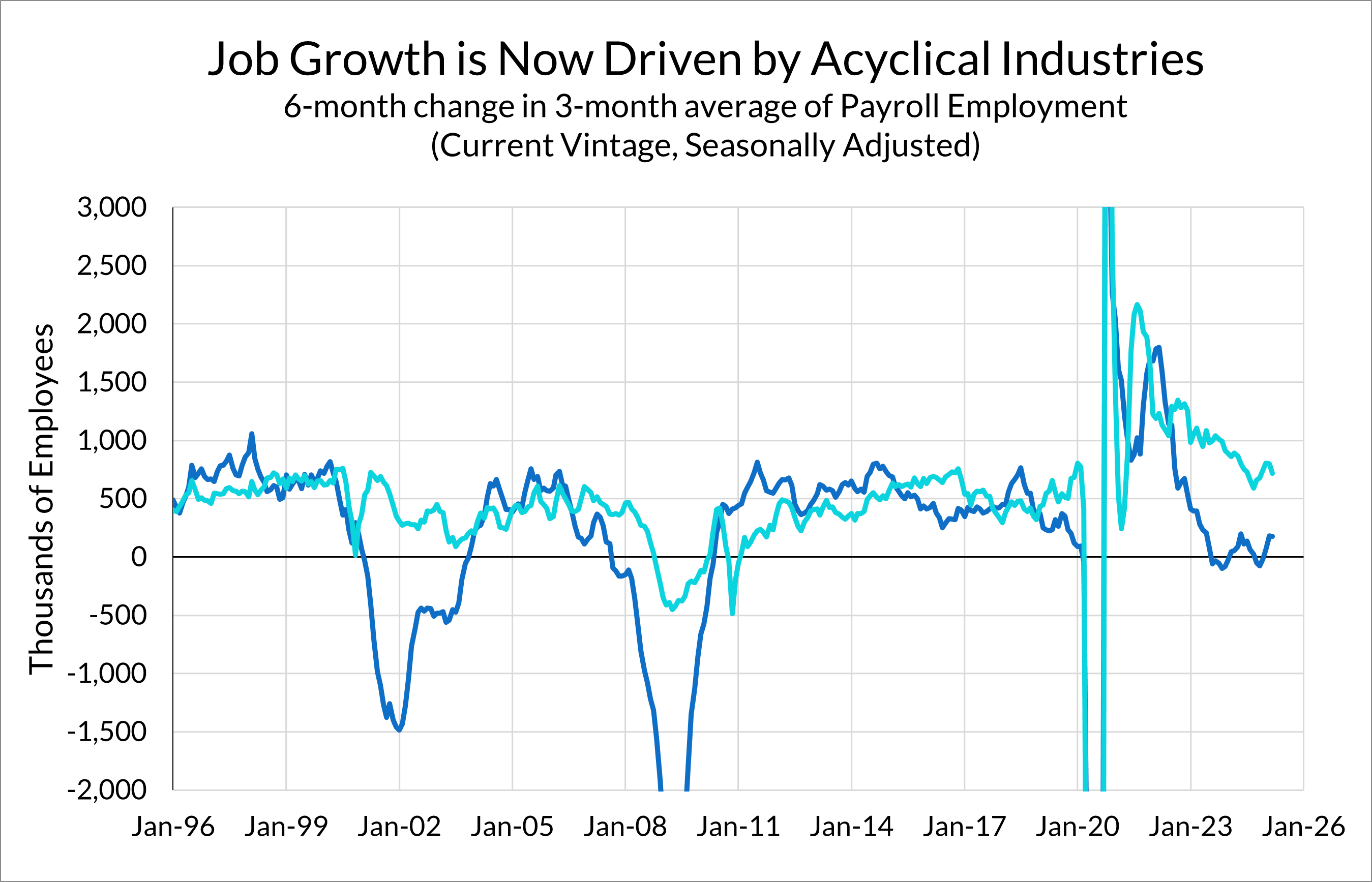

As of the time of writing, the hard data in the labor market—which comes out with a lag—still looks solid. But the current policy mix poses a significant threat to full employment. In the early months of 2025, we have been concerned about the increasingly narrow scope of employment growth. Job growth has been highly concentrated in “acyclical” service sectors such as education, healthcare, and government. Meanwhile, we have seen little job growth from more cyclical and interest-rate sensitive sectors such as manufacturing.

This mix of job growth was fragile to begin with. Strong growth in acyclical sectors was largely a product of those sectors catching up after recovering lower earlier on in the recovery, and likely to wane. Cyclical sectors were unlikely to see a pickup in activity absent further rate normalization from the Fed, which was still on hold as inflation remained elevated. Still, it was a solid labor market that was delivering job growth and wage growth, and may have been able to hang on until rate normalization unlocked a broader sectoral mix of job growth.

The last few months of fiscal policy have only strengthened the headwinds against the labor market. Even before the most recent round of tariffs, fiscal policy has been working against the sectors that are currently delivering job growth. DOGE-initiated layoffs of federal employees may receive the most attention, but the actual number of workers affected may not be that large from a macroeconomic perspective (and these may not show up in the labor market data until they stop receiving severance payments, due to the way that the BLS defines payroll employment).

From a macro perspective, the greater threat to employment may come from cuts in federal programs that support sectors such as education and healthcare. Already, we are seeing major universities imposing hiring freezes and outright layoffs in response to federal funding cuts. These cuts are also affecting hospitals, which may also face difficulties if Medicaid cuts are also implemented. Recreation employment may even be threatened by a slump in foreign tourism as potential visitors are turned off by the threat of being imprisoned for weeks for no apparent reason.

Add to that the last couple weeks of tariff policy. Despite the Trump Administration’s claims that one (of their many conflicting goals) of the tariffs is to create a renaissance in manufacturing, the blanket tariffs are only making it harder for American manufacturers, who rely heavily on foreign inputs. The outlook for residential construction is only going to worsen as the US imposes heavy tariffs on Canadian lumber, and the tariff play has failed to deliver lower mortgage rates. Retaliatory tariffs will make it more difficult for American manufacturers to sell their goods abroad.

With policy actively working against nearly every sector of the economy, where is strong job growth going to come from six months from now?

A Hostile Environment for Investment

The irony of the Trump Administration’s claimed mission to return America to a manufacturing powerhouse is that we were in the midst of a resurgence in American manufacturing, at least in certain key sectors. We were never going to return to a manufacturing-centric economy (not even if we lay off millions of federal employees as Scott Bessent suggests), and that was never a desirable outcome in any case. However, targeted policy support from the CHIPS Act, the IRA, and the IIJA was spurring an explosion in investment in manufacturing construction, green energy, and infrastructure.

Many of these initiatives are now under threat. Over the last three months, the new Administration has put a hold on or rescinded funding for clean energy projects. Trump called for an end to the CHIPS Act last month and laid off a significant portion of the staff implementing it. The Department of Energy is about to lay off thousands of workers and end billions of dollars in energy projects. Any business looking to make long-term investments will be wary of the possibility of a rugpull for at least the remainder of this Administration.

Elsewhere, federal support for research and development—a key factor in the success of the 1990s—is being cut. Universities are cutting graduate admissions and scientists are considering leaving the US altogether. Researchers are even reconsidering visits to the US out of fear of being arbitrarily detained.

Again, this all before the current iteration of tariff policy, which has only exacerbated the outlook for investment. Before Liberation Day, business sentiment was buoyed by the belief that Trump’s commitment to tariffs was either not genuine, a negotiating bluff, or would at least be reigned in by more sensible members of his team. Instead, the Liberation Day tariffs were far higher than most anticipated, using a completely nonsensical formula that may have been generated by AI. The Administration has multiple times indicated that they are somewhere between indifferent to and encouraged by a stock market selloff.

Even if the Administration reverses course on its most damaging policies, there will be lasting damage. It is hard to unring that bell. It’s now apparent that tariff policy is mostly being driven by Trump’s beliefs that tariffs are inherently a wonderful thing and that trade deficits are per se bad. Under the current institutional arrangement, he can essentially change tariff policy at will. Who knows what might lie in wait in other areas of economic policy, especially given how much unilateral authority the President is claiming across the executive branch?

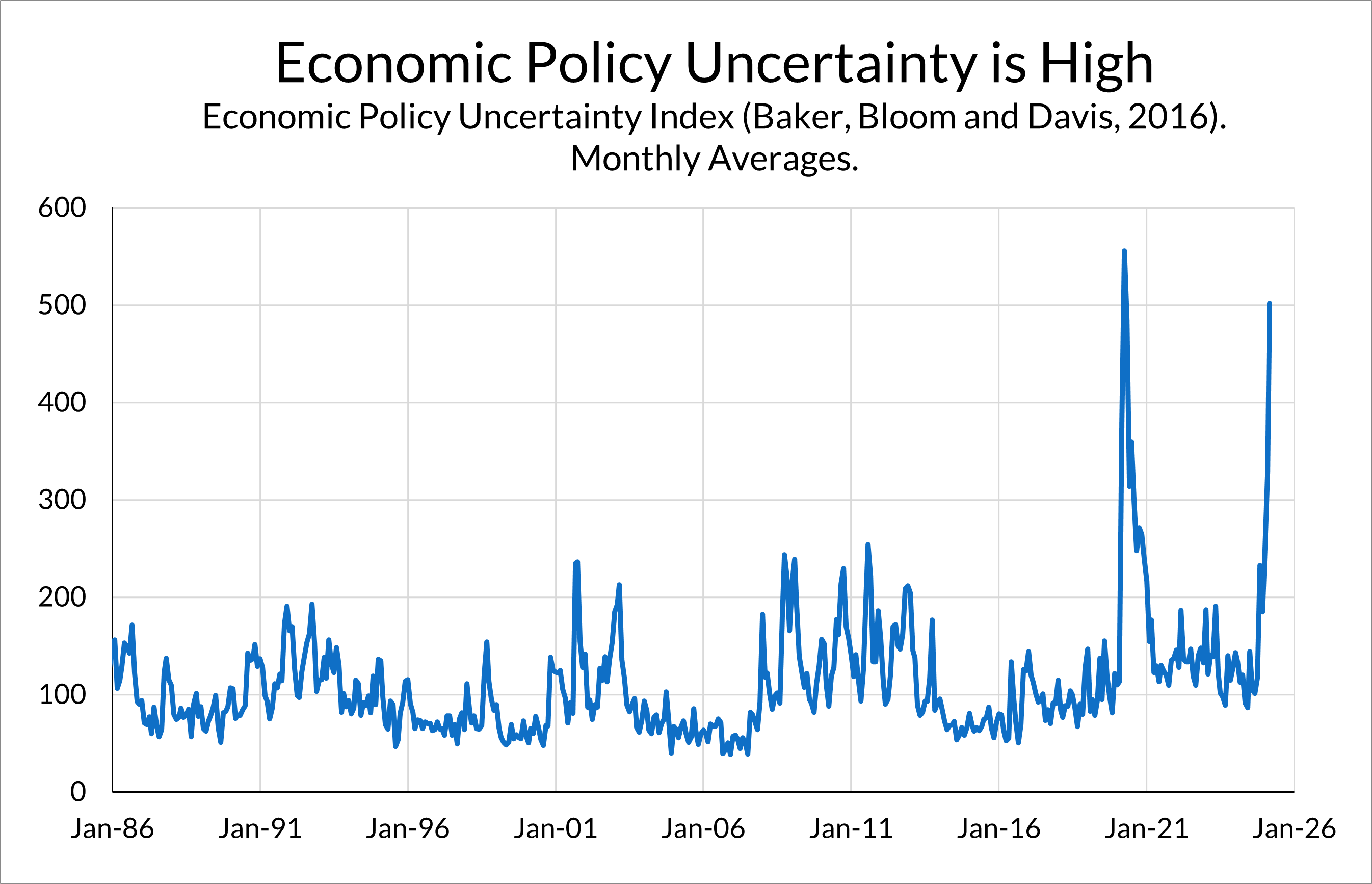

The economic policy uncertainty index, which was relatively low throughout the late-1990s, is now at its highest levels outside of the beginning of COVID. As of the time of writing this, Trump just announced that most of the “reciprocal” tariffs will be paused for 90 days, with a 10% blanket tariff taking its place in the meantime (except for China, which will be subject to 125%—actually, correction, 145%—tariff). It may be different by the time you read this. It may be different next week or even this afternoon. That is the level of policy uncertainty that business leaders are expected to make hiring and investment decisions under.

It is hard enough to plan out writing about economic policy in this environment, to say nothing of opening a factory, investing in long-term research and development, or any other type of capital expenditure.

Disrupting Our Supply of Basic Consumption Needs and Key Inputs

In the 1990s, the US benefited from supply-side stability. This was in part due to luck; we avoided some of the oil shocks that plagued other eras, and the Asian Financial Crisis helped keep foreign input prices low. But part of this was a product of policy as well; concerted efforts to encourage healthcare cost control led to a fall in the cost of employee benefits, promoting full employment. The resulting low inflation of the late-1990s encouraged the Federal Reserve to avoid tightening monetary policy even as the unemployment rate fell below their estimates of its “natural rate.”

Tackling supply-side stability—low and stable prices of key inputs and basic consumption needs—looked like our biggest challenge coming out of the COVID recession. The recession and subsequent inflation revealed how fragile our supply chains were. High inflation in key consumption areas such as food and shelter showed how that supply-side fragility could lead to inflationary pressures and a subsequent tightening of monetary policy.

We'd taken important steps towards securing our supply chains for the next shock. The CHIPS Act was making important steps towards building domestic semiconductor manufacturing capacity. The Department of Energy was using innovative strategies with the Strategic Petroleum Reserve to stabilize oil prices. There was more work to be done, especially in the areas of housing and healthcare costs, but it was a start.

Now, in 2025, policy is raising the cost of basic consumption needs and disrupting the supply chain.

Tariffs will be an obvious source of higher costs. I already mentioned the effect of tariffs on key inputs for manufacturing and construction, which will only exacerbate the housing supply issue (on top of any ramifications from deportations of migrant construction workers). Tariffs will also affect a large swath of food products, which are not on the tariff exemption list despite the fact that we cannot produce many of those food items domestically.

The administration may be publicly celebrating a drop in oil prices, but the instability in oil prices is a direct threat to domestic oil investment and production. The comments by the oil industry to the Dallas Fed Energy Survey are absolutely dismal, with one respondent saying “I have never felt more uncertainty about our business in my entire 40-plus-year career.” All of this is on top of the aforementioned dismantling of support for renewable energy projects.

When it comes to healthcare, instead of pushing for sensible healthcare cost reforms that don’t threaten patient outcomes, the Administration is instead threatening tariffs on pharmaceuticals and increasing payments to Medicare Advantage plans, which are rife with overpayments from “upcoding.” Meanwhile, Congress is considering making large cuts to Medicaid.

With all these supply shocks happening, it’s no wonder the Fed continues to be on hold. The last thing they want to do is to cut rates and see another resurgence of inflation, which is likely to happen (at least temporarily) with these tariffs. This delay in rate normalization will only put more pressure on rate-sensitive sectors and stymie investment.

The Dream is Slipping Away

Right now, the question on everyone’s mind is whether or not the tariff episode will push us into a recession. If a recession does indeed materialize (as was our base case, if the Liberation Day tariffs went into effect as planned), the cost of the current policy mix will be painfully obvious.

However, even if we manage to avoid the worst outcome, we should still remember what was lost if we fail to achieve another era of strong productivity growth. The cost of failure will be felt in terms of lower economic growth, wage growth, and investment for years to come.

Smart recession-fighting and investment policies gave us an opportunity to see another golden era of productivity growth, but we are actively squandering that opportunity. There is still a path back to the late-90s, but it is looking narrower by the day.