If you enjoy our content and would like to support our work, we make additional content available for our donors. If you’re interested in gaining access to our Premium Donor distribution, please feel free to reach out to us here for more information.

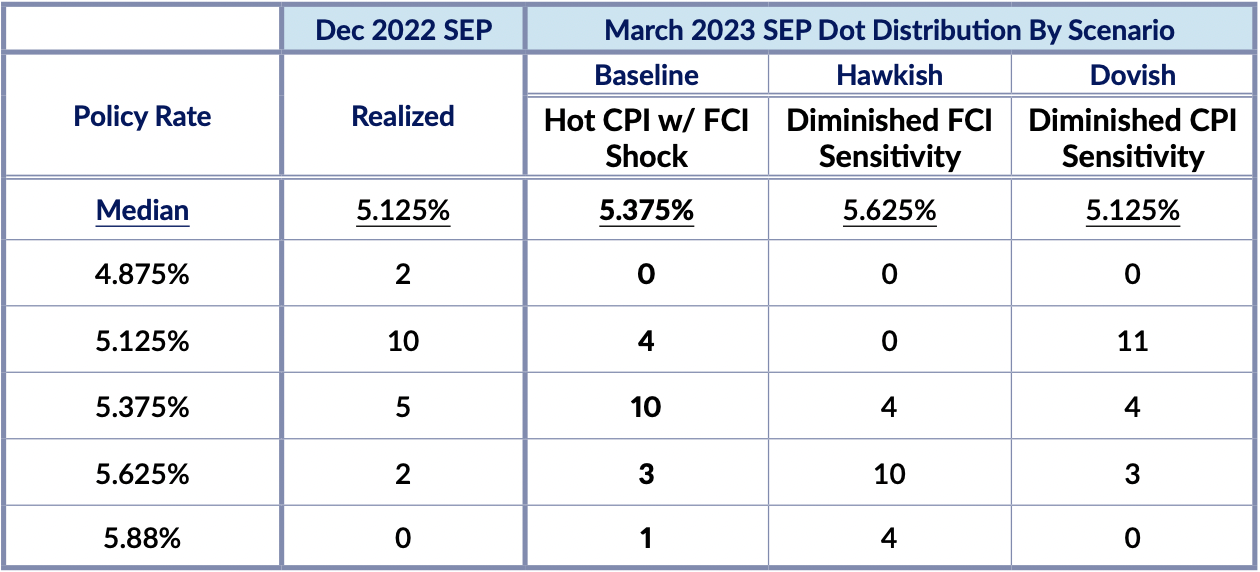

Our Scenarios For The Dot Plot

What to expect:

- Market pricing currently implies a 60% chance of a 25 basis point hike at the March FOMC meeting, but we see a marginally stronger base-case for a pause. In light of ongoing banking crisis challenges, the Fed’s own assessment of the banking system matters (they have informational advantages over market participants in assessing the state of the banking system). Recent Boston Fed President Eric Rosengren’s own concern and call for a pause likely reflects some FOMC members’ views right now. Of course following the market is always the easier call and may prove more prudent, but if there’s a time for the Fed not to follow market pricing, this meeting might be it. The entire FOMC was clearly blindsided by this dynamic and likely still wrapping their heads around its potential scope and scale. If the Fed does pause hikes in March, we would still expect it to be coupled with dots that signal an additional hike (maybe two) in 2023, with Chair Powell explicitly making further hikes contingent on arresting the risk of runs across the banking system.

- The situation is changing rapidly. Bank stocks continue to make new lows and there are still unresolved dynamics regarding SVB’s acquisition, deposit flows through the system, and its ultimate impact on bank lending. If the goal of interest rate hikes is to tighten financial conditions, this episode has triggered a sizable source of exogenous tightening. Banks’ ability to raise capital is structurally more challenging now and FOMC members risk making it harder to raise capital if the Fed is insistent on tightening financial conditions further.

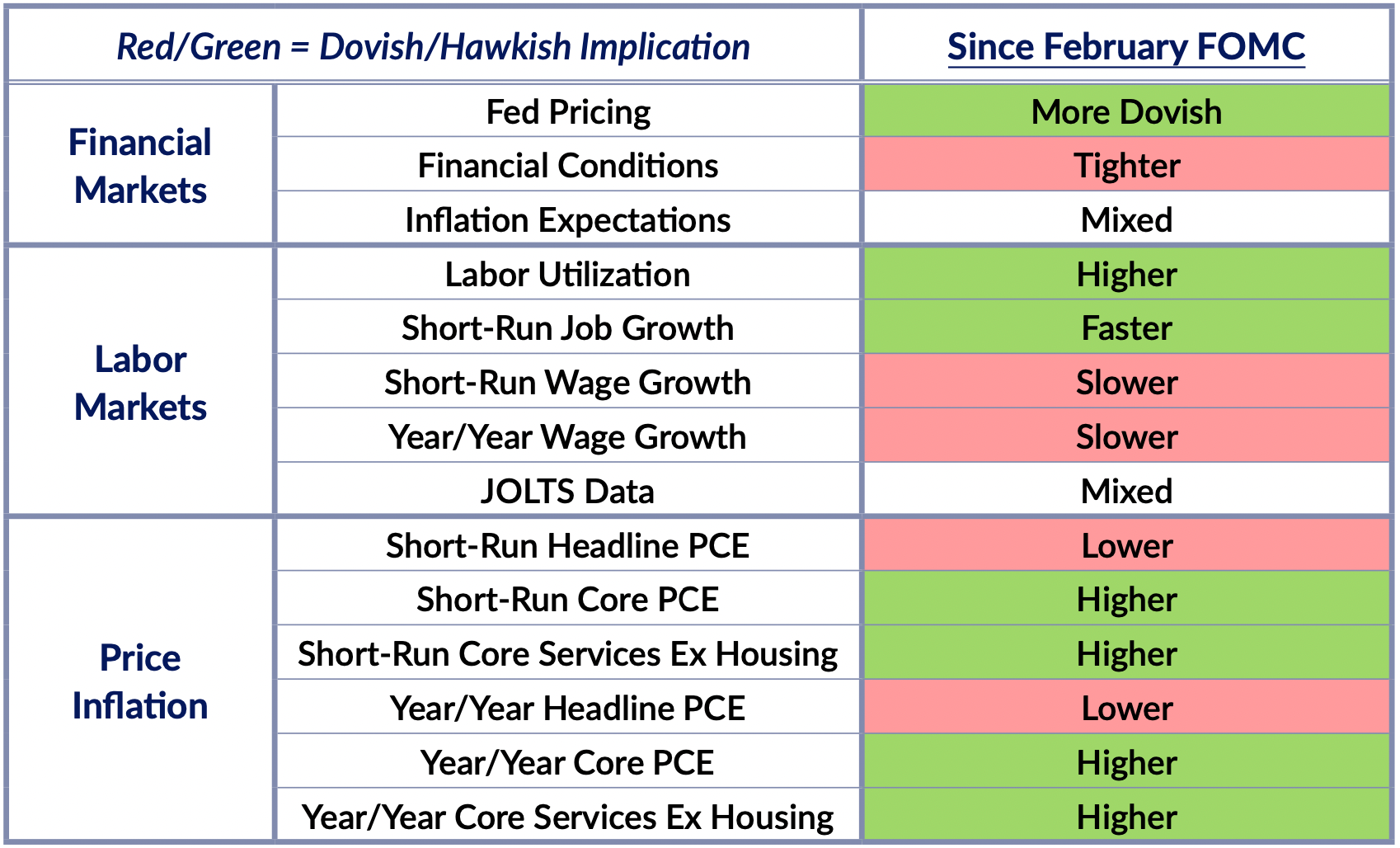

- The Fed will maintain a highly hawkish posture on inflation, even though the labor market has continued to show signs of (non-recessionary) cooling. CPI inflation, especially in the non-housing core services the Fed cares so much about, is still elevated and employment remains strong. However, when one looks at wages, quits, and hires, and labor force participation, the labor market continues to cool. If the Fed wants to stick to its story that core services inflation is wage-driven (and we’re skeptical of that), this could have been their cue that accelerating rate hikes and higher unemployment are not necessary to achieve disinflation. Instead, we expect more emphasis on low unemployment and high job openings in Powell’s press conference (if he even gets a question specifically on the state of the labor market)

The Developments That Matter:

- The big story is, of course, the fallout from the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. The Fed’s interest rate hikes have finally helped break something, and the FOMC will be scared of breaking things further. Financial conditions have tightened substantially sharply and suddenly, and the outlook over the near-term is highly volatile. Oil and other commodity prices have dropped, implying a weakening outlook of economic activity.

- The labor market has been benevolently cooling. It’s hard to believe that less than a week ago, we got jobs numbers that showed strong employment driven by increased labor force participation, decelerating average hourly earnings, falling quits, and a slight tick up in layoffs. On the key metrics that reliably explain or forecast employment and wages, we are seeing a reversion back to evidently sustainable pre-pandemic outcomes. It is probably still more convenient for the Fed to point (solely) to job openings as a source of confirmation bias, simply because the Fed presumes high services inflation to be primarily wage-caused. But there is a brewing tension between the Fed’s convenient descriptions and the realized data.

- The inflation data from since the last meeting has been discouraging, with core services still running hot, market rents not yet feeding through to CPI rents, and the goods deflation cavalry not arriving. In the absence of the SVB event, Chair Powell seemed keen to reaccelerate the pace of hiking with a 50 basis point hike. We expect that used car prices will surge in the upcoming 2-3 CPI releases, fomenting more risk that the Fed continues to keep policy tight longer than is optimal for long-term stability.

What We Think the Fed Should Do: Pause, Look, and Listen

- If the Fed’s interest rate tools work through financial channels, the Fed needs to respond accordingly. Those who think the Fed should stay laser-focused on macroeconomic variables like inflation need to consider how interest rates work on the economy. If financial conditions are exogenously tightening through the banking channel, that diminishes the growth outlook and weakens the case for the Fed to deliver further tightening, especially under our preferred framework that primarily aims for stable gross labor income growth.

- Given the elevated tail risks associated with banking transmission mechanisms, we think it is prudent to pause and evaluate the full scale of this dynamic. The dots and future meetings offer ample avenues to preserve hiking optionality, but we could be in the midst of a stepwise shift to the growth outlook. There’s a fundamental asymmetry and nonlinearity to how financial constraints bind; further damage is very difficult to reverse quickly.

- Income trends continue to show more signs of normalization even if there is less progress on prices; given the uncertainties associated with rapid tightening a 50 bp hike never made any sense. Just before the Fed’s February FOMC announcement, we got the 2022 Q4 ECI print, showing significant wage deceleration during the end of 2022. We’re still in somewhat foggy territory until the next Employment Cost Index print, but the labor market story over the past few months has mostly been about strong but slowing employment, cooling quits and hires, and slowing wage growth in lower-tier wage measures. Even if the slowing wage growth hasn’t translated to disinflation in the core services sector (contra the Fed’s wage-driven views), lower income growth should reduce forward consumption growth and demand-side inflationary pressure in the aggregate (very hard to parse how this will split between goods and services). In the absence of banking panics, our framework would likely prescribe incremental financial conditions tightening (growth is cooling but still above our threshold floor; inflation risks are elevated).

More broadly, the events and data releases over the past week really drive home the fact that the Fed needs to be explicit about how its tools work. The Fed has basically said over the last week, “we want to tighten financial conditions and we need to be willing to throw people out of work. Wait, no, not like that.” At the press conference, the press corps should be asking “OK, then how?” What is the Fed thinking, specifically, about the path from interest rates to unemployment to inflation? We’re glad there is at least some limiting principle to how much collateral damage the Fed is willing to impose, but it’s not at all clear what that principle really amounts to. The Fed should be explicit about how rate hikes work in practice, not just in theory.

The Fed needs to clarify how it intends to tighten financial conditions, and how it will do so without threatening financial stability. It is clear that the Fed has not been sufficiently diligent in monitoring how its monetary policy interacts with its financial supervision responsibilities. Given the importance of that transmission mechanism and its interaction with financial stability challenges, it raises serious questions about how the Fed is thinking about how its tools work on the economy.

Charts: Financial Conditions

Charts: Wages and Labor Income

Labor Market Dashboard

Wages are Decelerating

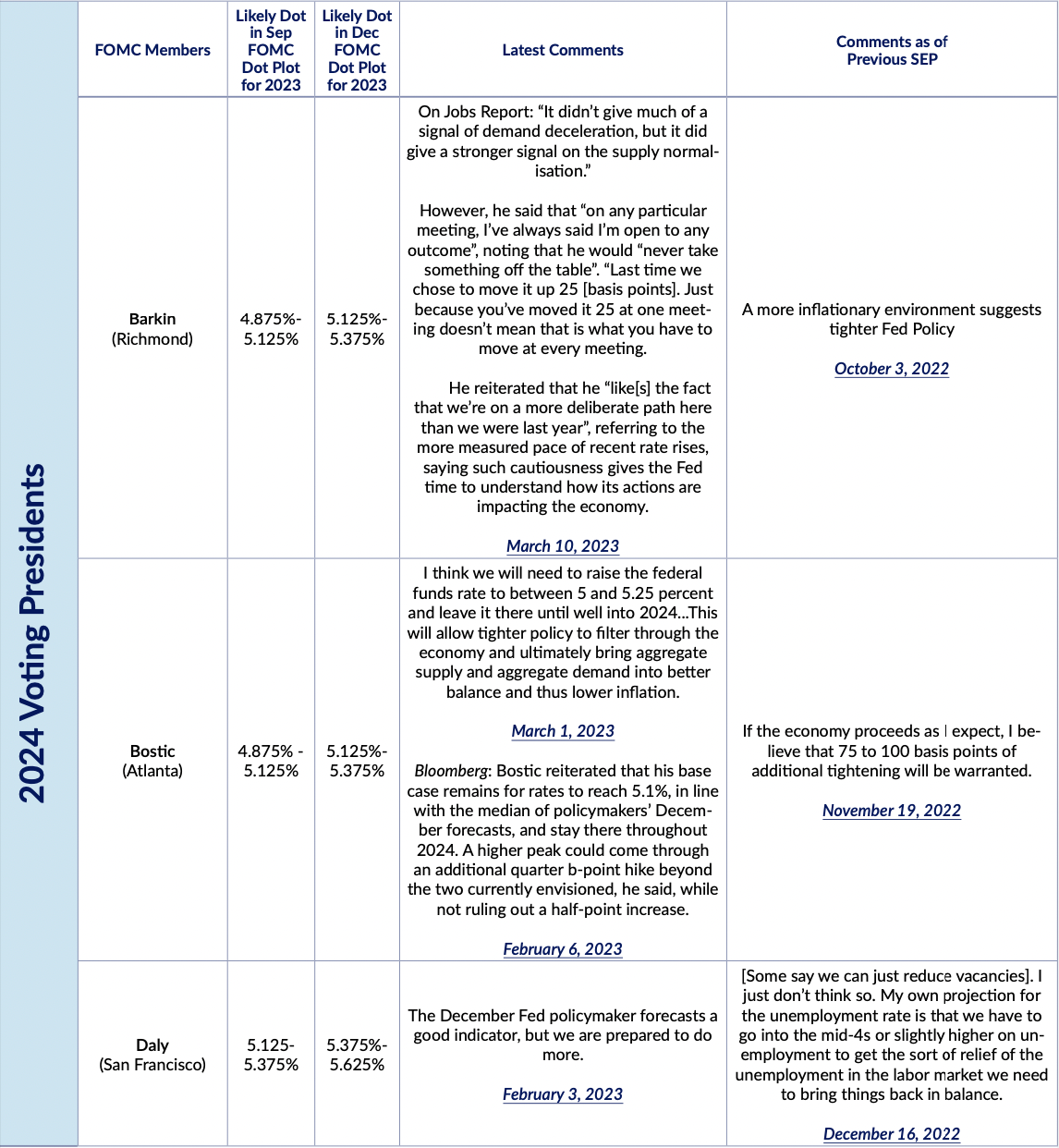

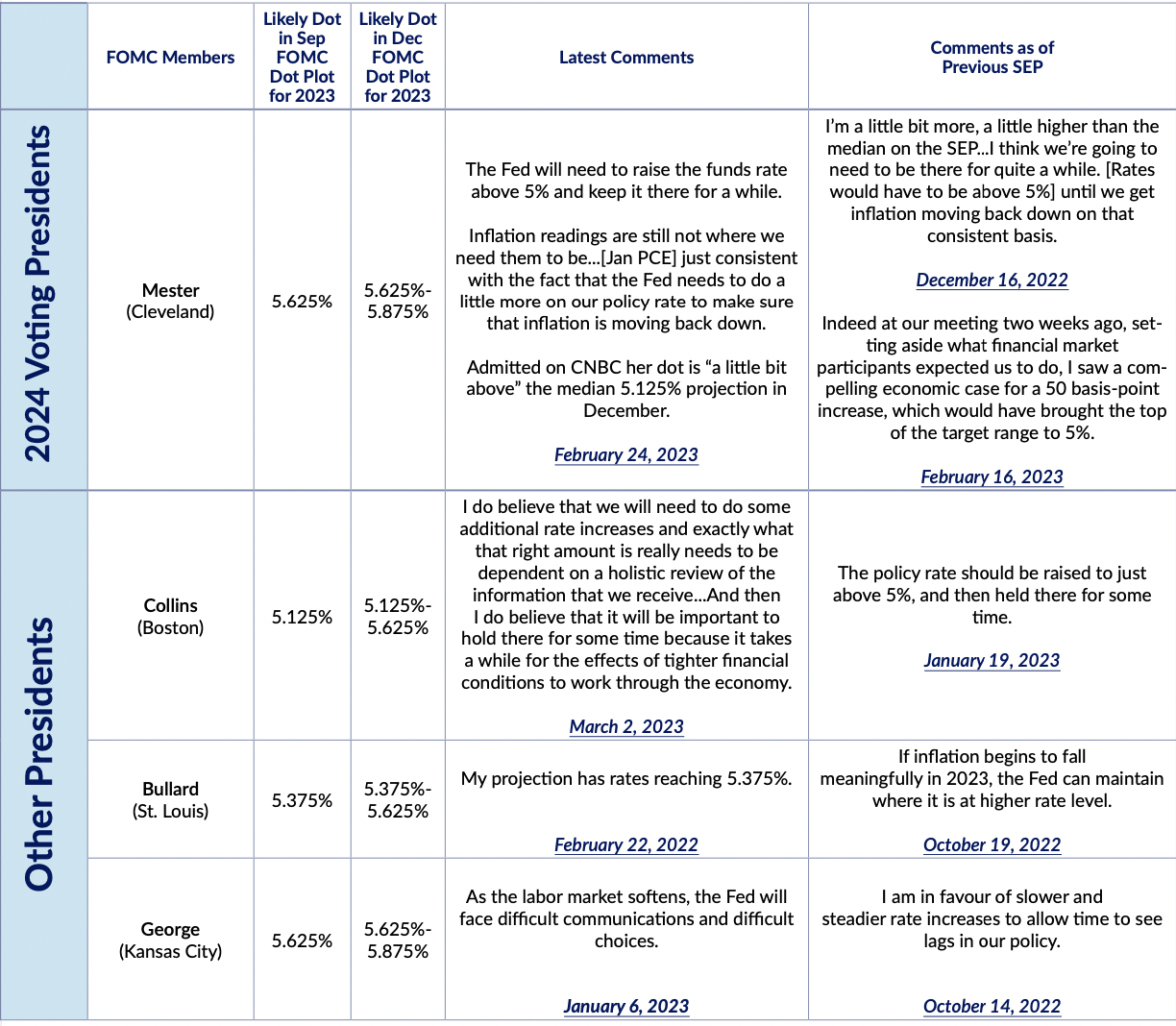

Latest Fedspeak

Monetary Policy Comments (Pre-SVB Failure)