The labor market added 12,000 net jobs in October, with negative revisions (-81,000 and -31,000 to net jobs growth in August and September, respectively). Due to the October payroll number marred by hurricanes and the Boeing strike, the real signal comes from the household survey (where those who are absent due to weather are still counted as employed) and the negative revisions to previous months. The unemployment rate remained flat at 4.1%; prime-age employment and labor force participation rates both fell by 0.3pp. The Employment Cost Index for September continued to cool, coming in at a 3.2% annualized increase from the previous quarter. Hires in JOLTS picked up locally but all JOLTS indicators are reading significantly cooler than 6-12 months ago.

This is the last big data release before the November FOMC meeting, which looks like it will still be a lock for a 25 bp cut. There’s still enough concern over elevated inflation that December still looks uncertain and we’ll expect them to try to keep their options open for a pause in December. From our view, the mixture of slow ECI growth (relative to productivity growth), anemic hiring activity, and the now-clearer downward trend in payroll employment after revisions all reinforce the wisdom of going 50 bp in September and the need to continue with interest rate normalization.

Three cheers for the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which also announced that they are suspending plans to reduce the sample size of the Current Population Survey after receiving stop-gap funding from Congress.

The Actual Signal from Payrolls: Negative Revisions

Everyone knew coming into this report that parsing the October labor market data was going to be difficult due to the idiosyncratic effects of the hurricanes and the Boeing labor strike. The latter certainly seems to have affected the payroll data, with employment in transportation equipment manufacturing falling by 44,400 in September. The effects of the Hurricane are less certain, and there may be significant noise in this month’s establishment survey. The initial response collection rate, at 47.4%, is its lowest since January 1991 (for reference, the average response rate last year was around 65%). According to the BLS the low collection rate was not due to hurricane effects but rather the shorter collection period in September.

The addition of 12,000 net jobs came in far below pre-release consensus estimates, which were north of 100,000. Chris Waller said he expected hurricane and strike factors to reduce payroll growth by over 100,000 this month. It’s hard to say with any certainty, but it seems likely that payroll employment growth for this month is running at or below the range of estimates for short-run breakeven employment growth.

More signal came from the significant downwards revisions to August and September. Even if one sets aside the questionable figure from October, the payroll growth trend looks worse with this month’s data. The previous month’s data saw a pop in payroll growth, and it looked like the labor market might even be reaccelerating by that measure. Some even said it suggested the Fed made an error by cutting by 50 bp in September. However, after the revisions to previous months, the trend of payroll growth looks much less favorable (even if September growth was solid).

While pre-revision trend payroll growth looked like it might have been stabilizing or even reaccelerating, after today’s data it looks much more like payroll growth is trending down.

Where the revisions are coming from: mostly professional and business services. This sector looked like it might be stabilizing, especially in the September report. The situation looks more dire now, with five straight months of net job losses.

Compensation Growth is Now… Maybe Too Low?

We got another quarter of Employment Cost Index data this week. ECI (total compensation, all civilian) came in at 3.9% over the year and 3.2% quarter-over-quarter. While this is still a bit higher than pre-2020 growth rates of ~3%, it is totally justifiable under the Fed’s “inflation plus productivity” framework. 3.2% is solidly within that range using the pre-2020 1.0 to 1.5% trend productivity growth rate trend, and it may even be too low if the recent trend of productivity growth rates exceeding 2.0% continues.

Right now, compensation growth is being pulled up by higher growth rates in government and union workers. These are workers whose compensation tends to lag compensation in other workers, so some of the strength in ECI growth represents an impulse from past labor market tightness that will fade going forward.

What’s with the Weak Quit Rate?

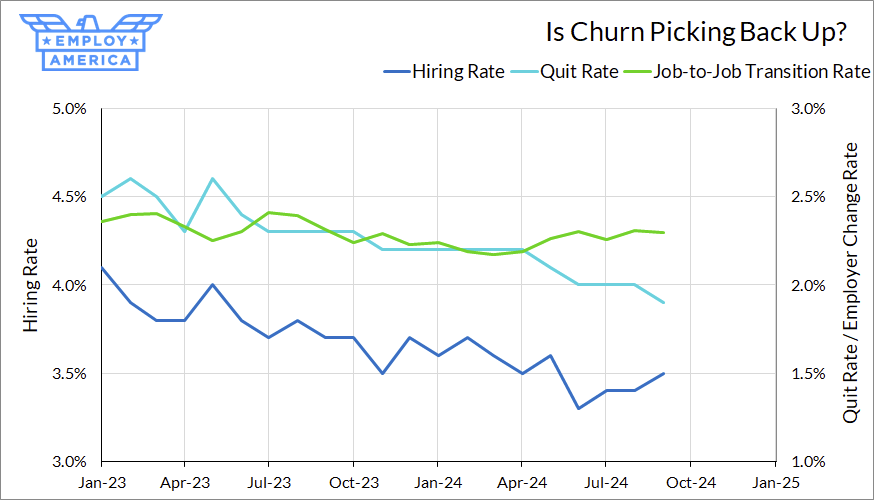

Over the last few months, quits have continued to fall while hiring has picked up slightly. Both measures are significantly lower than their 2019 levels, and quits look especially weak. While we were on the pre-pandemic “quits Beveridge curve” earlier this year, it increasingly looks like we are falling below it. If you were to choose one metric to argue that this is a weak labor market, you’d probably pick quits.

It’s worth remembering that quits are a data point taken from the JOLTS, which is a survey conducted among employers. Because of that, the quit rate is unable to distinguish between quits to other jobs and quits for other reasons. Likewise, the hiring rate does not distinguish between hires from non-employment and hires of already-employed workers.

One way to shed light on this dynamic, which I covered last month, is the employer-to-employer transition rate in the household survey, as calculated by Fujita, Moscarini, and Postel-Vinay (2024). And there, it looks like job churn is stabilizing or even picking up:

What does this mean for our readings of quit and hiring rates? On one hand, this would seem to indicate that quitting to move to other jobs is still healthy; instead, the decline in quitting represents a decline in quitting to non-employment. This is one reason why participation and employment remain high even as the unemployment rate has climbed. And, it indicates that job churn is still going well.

Turning to hires, this would indicate that the pickup in hiring is more due to poaching than hires of the non-employed. This tracks with the rise in the unemployment rate and a slight decline in workers’ perceptions of how easy it would be to find a job if unemployed.

To sum up, the labor market currently looks:

- Fairly stable in terms of employment rates;

- Increasing in unemployment (over the past twelve months) due to higher participation, including from fewer labor force exits;

- Still decent for those who are employed, including in terms of finding new jobs;

- Not great for those who are unemployed and trying to find a new job.

The Fed

This month’s data doesn’t change much about our opinion of the long-term trajectory of the labor market. The payroll revisions and ECI data solidify the trend of a slowing labor market and the elevated risk of a labor market that goes beyond slowing to outright deterioration, even if we don’t see it now. It bolsters the case for continuing with interest rate normalization. 25 bp in November looks like a done deal, but December may hinge on the remaining labor market and inflation data for this year, especially after a warm September inflation report.