The labor market added 114,000 net jobs in June, with slight negative revisions to previous months. The headline unemployment rate increased by 0.2% to 4.3%, mostly driven by temporary layoffs presumably related to Hurricane Beryl. The Sahm statistic is now 0.53, above the oft-cited 0.5 threshold. Prime-age employment rates increased to 80.9%, matching its post-pandemic peak. Prime-age labor force participation continued to climb, hitting a new high of 84.0%. JOLTS measured showed lower churn, with both layoffs and hiring falling this month. Wage growth continued to slow.

With the rise in the unemployment rate, this jobs report looks very bad, especially for a Fed that has been downplaying the need to act urgently against labor market risk. Under the hood, the month-to-month change from June to July is less alarming than the headline unemployment rate suggests. However, the data from July is a continuation of what we’ve already seen in recent months: the labor market is continuing to slow. Even discounting the effects of Hurricane Beryl, the labor market has slowed enough that a July cut now looks like it was, in retrospect, the appropriate move and a 50 bps cut should be actively considered as the base case for September.

A Bad Unemployment Rate Print

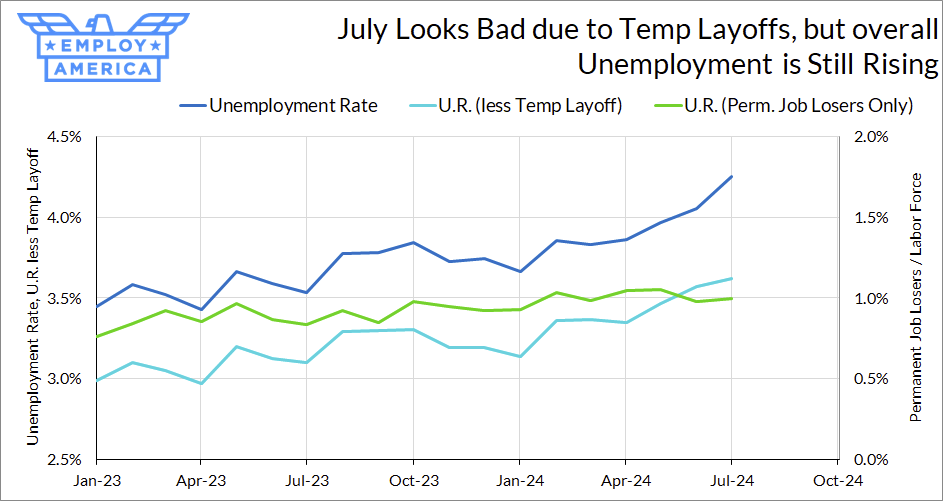

How bad is that increase in the unemployment rate? At first glance, it looks very bad. The unemployment rate has now breached the 0.5 threshold for the Sahm rule.

Looking under the hood, July’s increase in the unemployment rate looks less worrying. Most of the increase in the number of unemployed people can be attributed to an increase in the number of workers on temporary layoff. The best-case (and plausible) scenario is that this is due to Hurricane Beryl. It’s hard to say for sure; it would be consistent with the rest of the household survey (the number of workers with a job but not at work due to weather spiked to 1.1 million, up from 164,000 last July). However, there’s little evidence of weakness in the construction and leisure and hospitality.

The unemployment rate, stripping out those on temporary layoff, still increased in July, but only slightly. The more important takeaway is that July continued to deliver more of the steady weakening in the labor market we’ve been seeing since mid-2023.

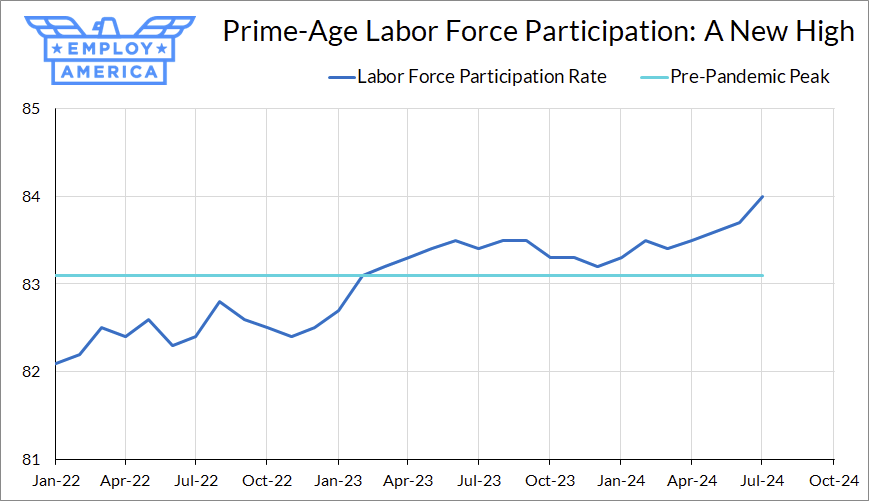

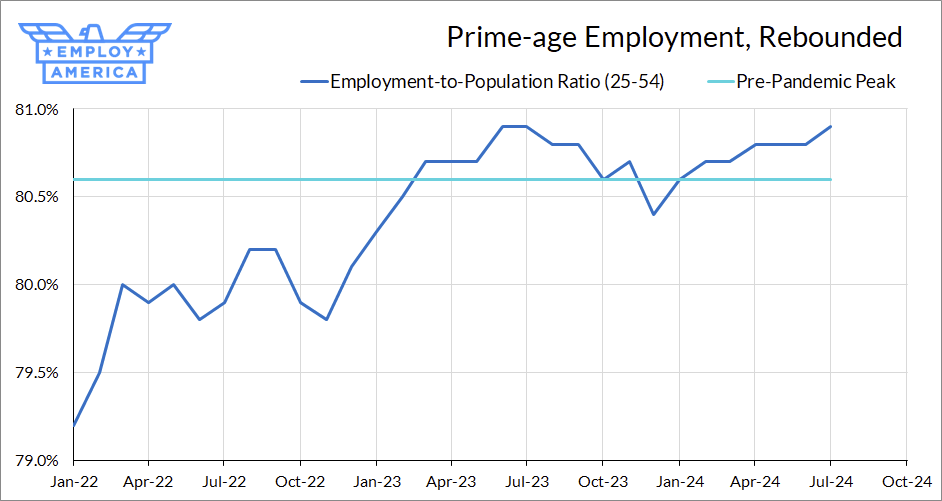

While a small part of that increase is due to workers suffering from permanent layoff, most of the increase in unemployment is attributable to new entrants and reentrants. Since the beginning of this year, participation has risen sharply and prime-age employment has returned to its post-COVID peak in mid-2023.

If there’s one reason why the Sahm rule is not as worrying as it seems. While the Sahm statistic has been increasing, that’s mostly a product of labor force participation increasing faster than employment. That doesn’t mean this is a hot labor market anymore though—the recent increase in employment merely recovers what was lost in late-2023. Prime-age employment has been moving sideways for at least a year.

The Softening Continues

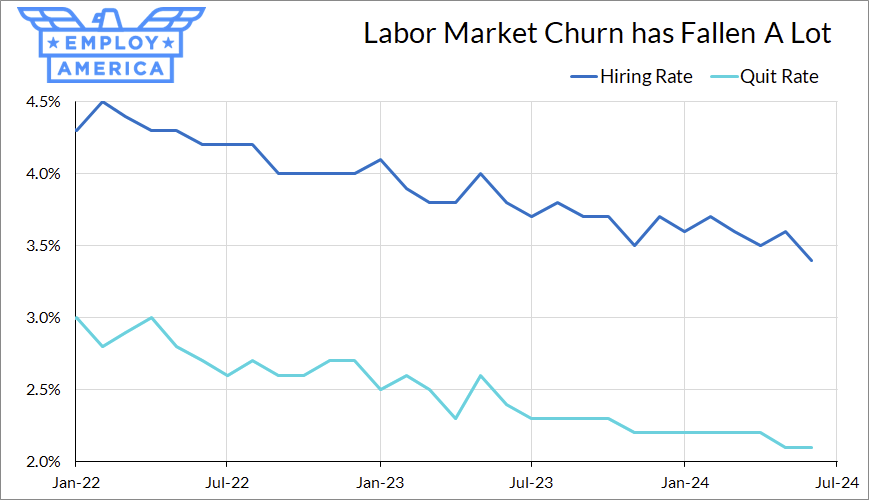

July’s data also brought further evidence of a softening labor market in labor market churn and wages. Hiring slowed again in June, to 3.4%. This level of hiring represents a new post-COVID low and is comparable to hiring levels in 2014. The quit rate remained at 2.1%, at 2016 levels. While layoffs did fall from 1.1% to 0.9%, this in and of itself does not guarantee that risks to the labor market are low—as I wrote earlier this week, layoffs, especially in JOLTs, are often a lagging indicator of labor market weakness.

Wage growth, too, continues to slow. Anyway you look at it, 12-month wage growth has continued to steadily decline. 12-month ECI growth came in a hair above 4%, and core non-housing services wages have grown by just 3.1%. This is a bit above what would be considered consistent with 2% inflation under normal circumstances—but easily the “correct” level given the current spate of high productivity growth we’ve been experiencing.

50 Should be the Base Case now.

After the FOMC meeting, I wrote that the Fed should actively consider a 50 basis point cut in September to avoid being behind the curve after holding in July. Today’s jobs report only solidifies that; the slowing we saw in the labor market before today was only confirmed and continued. A 50 basis point cut should be the base case after today and further slowdowns in the remaining jobs and inflation reports between now and the September meeting may bolster the case for more drastic action this year.

The case for cutting does not rest on the argument that the labor market, right now, is bad. It is not (4.3% unemployment rate notwithstanding). But with rates this restrictive, how long does the Fed really think it can hold out before the labor market turns sour? Layoffs are low now—but it may take rate cuts to maintain that situation.

At the July press conference, Nick Timiraos asked a question echoing a sentiment we’ve expressed before: just as the Fed does not believe it should wait until inflation is at 2% to cut, shouldn’t that apply to the balance of the labor market as well? Powell’s answer was basically that they’re well-positioned to respond to any elevated risk, indicating a responsive rather than proactive mindset.

This is not a poor way to manage labor market risk, especially given two other things Powell said on Wednesday: that he “would not like to see material further cooling in the labor market” and that he thinks there will be significant policy lags when rates are lowered. The combination of those two reasons means we should be cutting now (or rather, should have cut already) in order to preserve the balance in the labor market we’re seeing now.