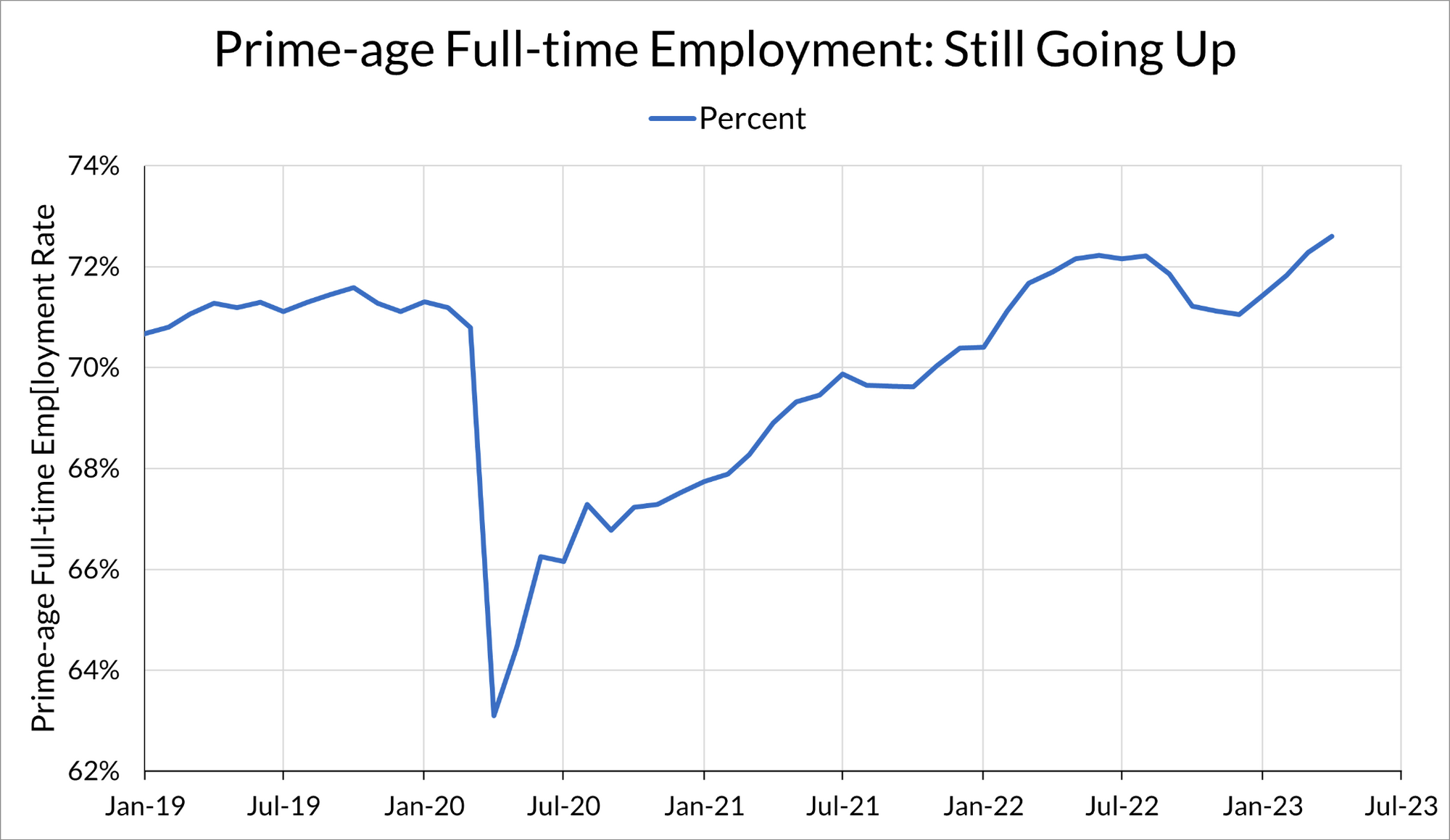

The data from the April labor market show continued labor market strength. As was true last month, almost all employment-based indicators show improvement from the previous month.

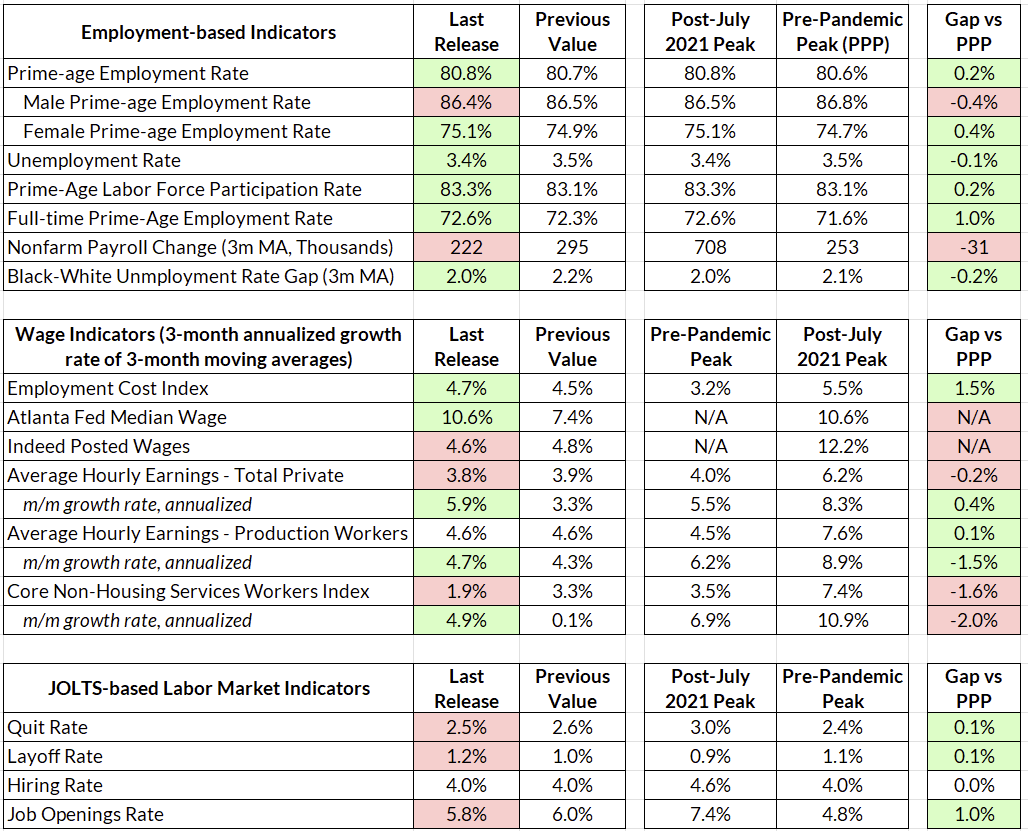

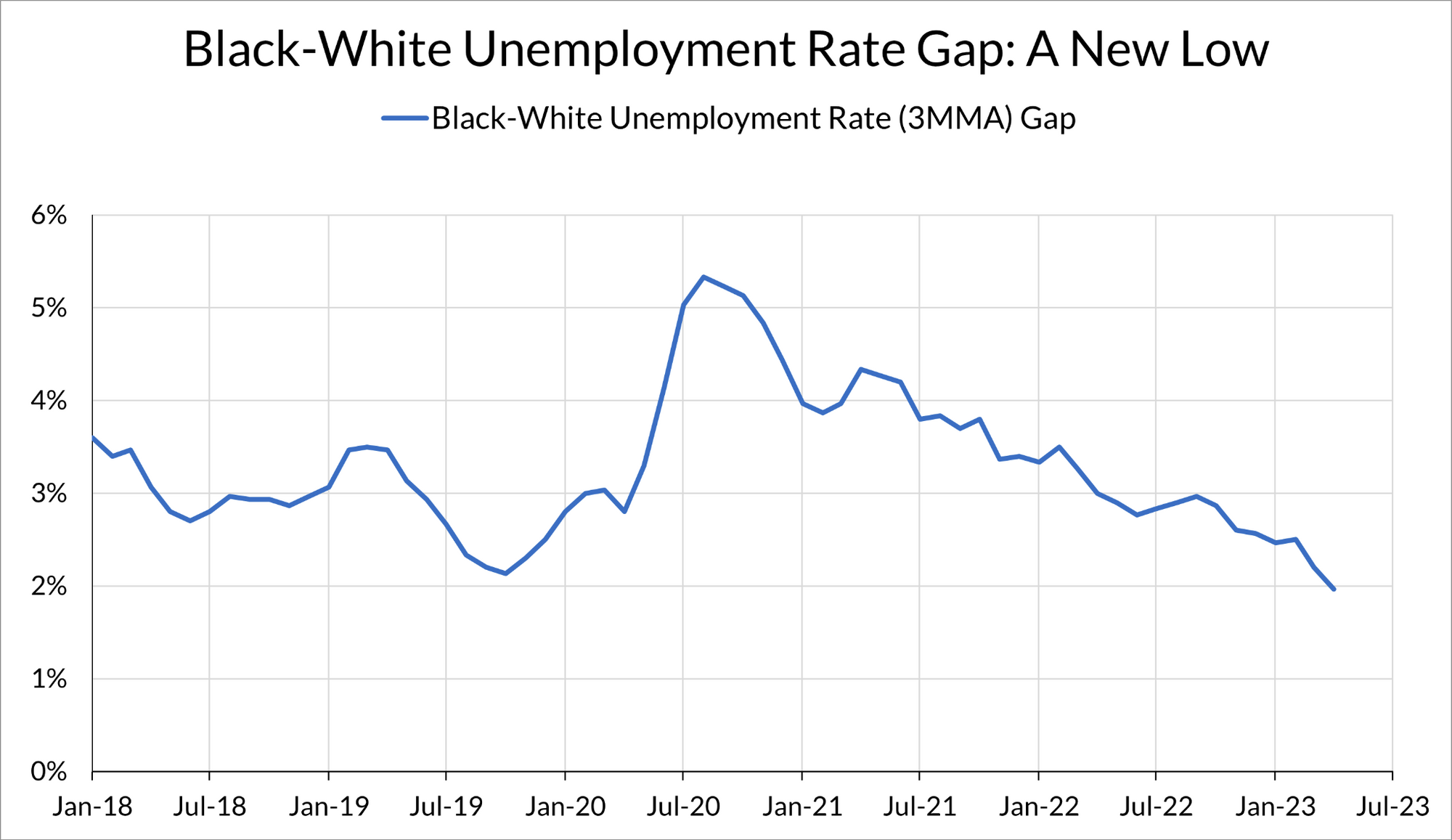

The headline unemployment number fell from 3.5% to 3.4% as employment continued its steady march upwards. The prime-age employment rate continued to climb, from 80.6% to 80.7%, as it has since November 2022. The full-time prime-age employment rate continued to rise to 72.6%, and the black-white unemployment gap fell from 1.8% to 1.6%, as the black unemployment rate fell below 5.0% for the first time ever. The establishment survey showed a strong 253,000 jobs added in April. We are now at the point where many labor market utilization numbers—unemployment, employment, participation, full-time employment—are beyond pre-pandemic levels. We shouldn’t treat 2019 as a goal to return to; new highs are both possible and desirable.

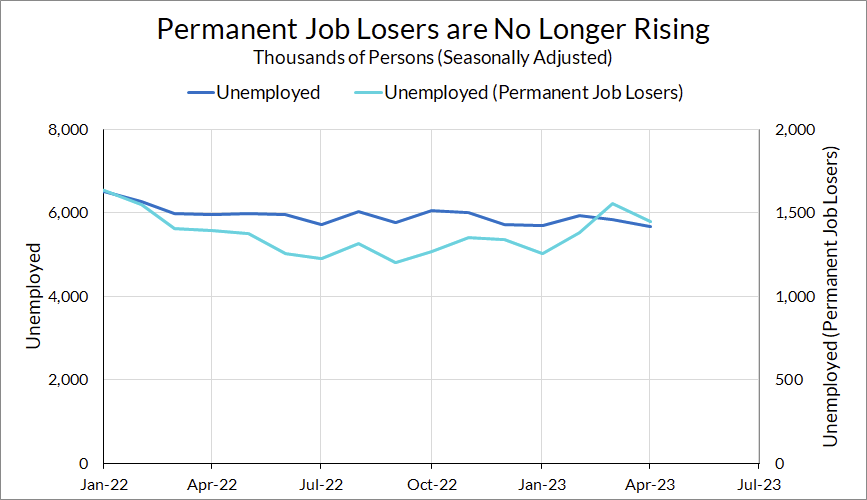

Last month, we flagged the increase in permanent job losers as the one worrying sign of labor market deterioration in the employment situation data. Luckily, the recent upwards trend in this series, driven by white-collar workers, took a break this month. More granular data will be available later this month when the CPS microdata is released, but the permanent job losers count fell this month and the number of unemployed for less than five weeks fell.

The strength of this report, combined with persistently higher inflation readings, means the Fed is less likely to cut interest rates. They’ve already signaled that they’re willing to stomach a recessionary rise in unemployment to fight inflation, and the continued strength of the labor market will, in their minds, justify keeping interest rates high.

Labor Market Dashboard: April 2023

The Pre-Covid Peak is not the Limit

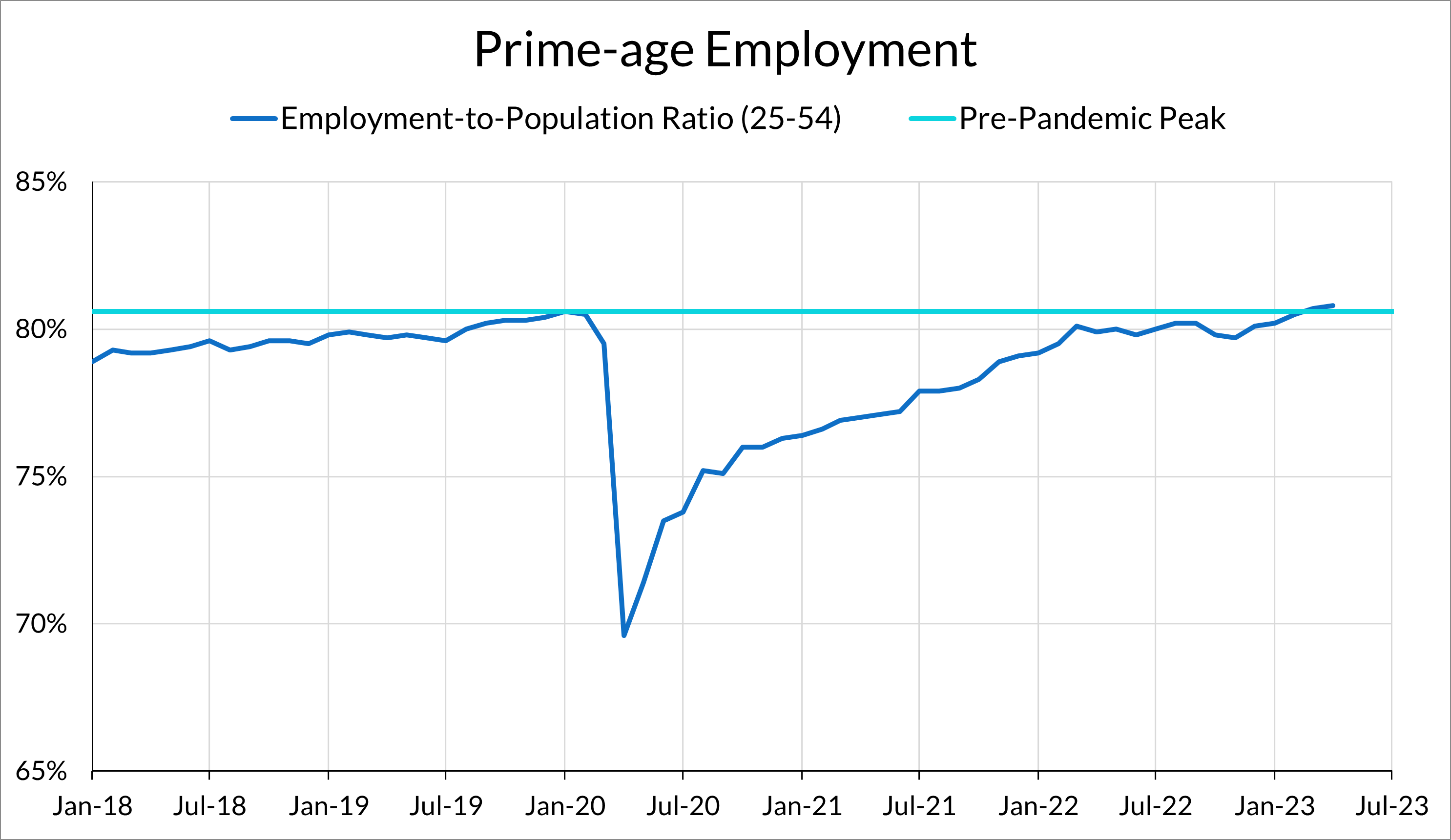

Once again, the employment numbers from this month are strong. Prime-age employment for both increased to 80.8%, and prime-age labor force participation is beyond its pre-pandemic peak and now at its pre-Great Recession peak.

The prime-age labor force participation rate rose to 83.3%, another post-COVID high and a level not seen since January 2007. Once again, we are getting something from labor supply; we are seeing that the answer to “worker shortages” is to bring people off of the sidelines into the labor market, not to destroy labor demand and increase job losses. Running the labor market hot gradually boosts labor force participation.

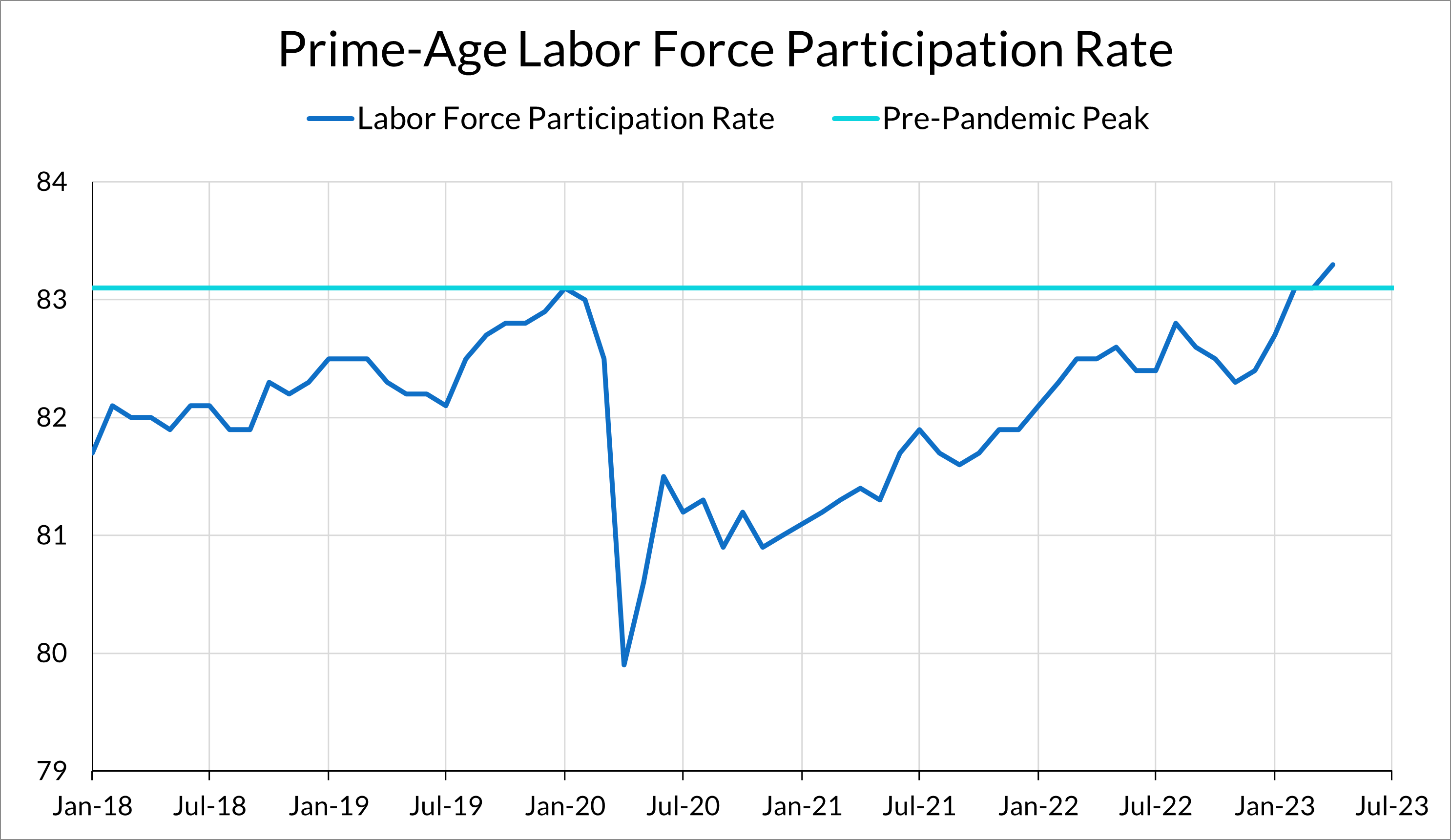

Last year, I was worried about a local fall in full-time employment. Since then full-time employment has completely recovered and broken through 2019 levels, making a new high this month. Prime-age full-time employment is up from 72.2% to 72.6%.

Finally, the black-white unemployment rate gap fell once again, from 1.8% to 1.6%, another historic low. A tight labor market is generally beneficial for workers, but especially so for the least advantaged groups.

A Sign of Relief from White-Collar Layoffs

In recent months, we have been worried about the rise of layoffs in the data, with unemployment claims rising (but remaining at historically low levels), JOLTS layoffs rising, and the number of “permanent job losers” sharply increasing in recent months. Last week, I showed that the rise in permanent job losers in the household survey looked like the white-collar layoffs we’ve been hearing about in the media.

Fortunately, in April the rising trend in permanent job losers (unemployed who report job loss as a reason for unemployment and are not on temporary layoff) was arrested. The number of permanent job losers fell in April from 1.55 million to 1.45 million.

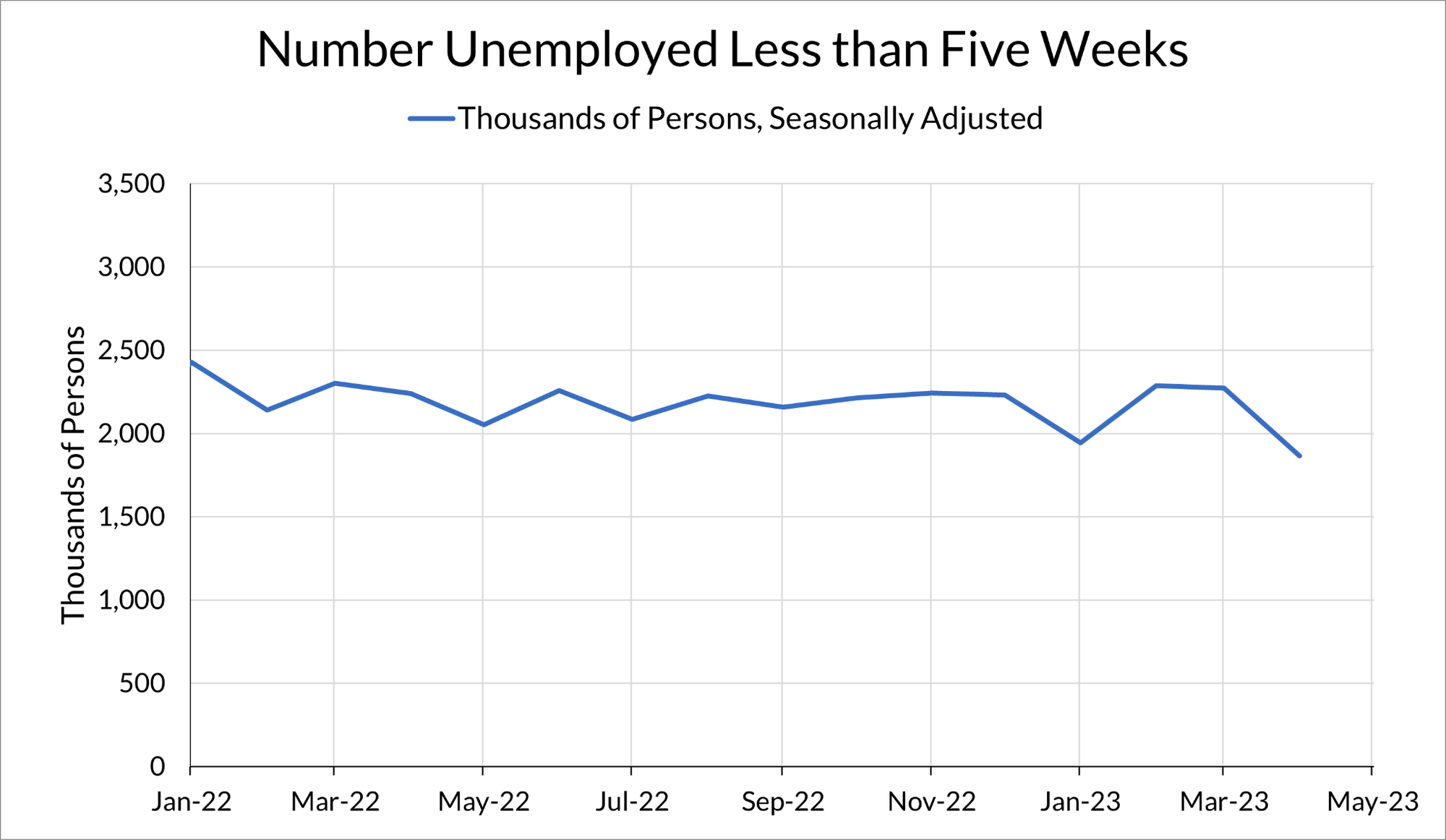

While the levels are still higher than throughout 2022, the local trend points towards a break in the latest wave of layoffs. We can also see this in the unemployment duration data, with the number of recently unemployed falling to a new low in April.

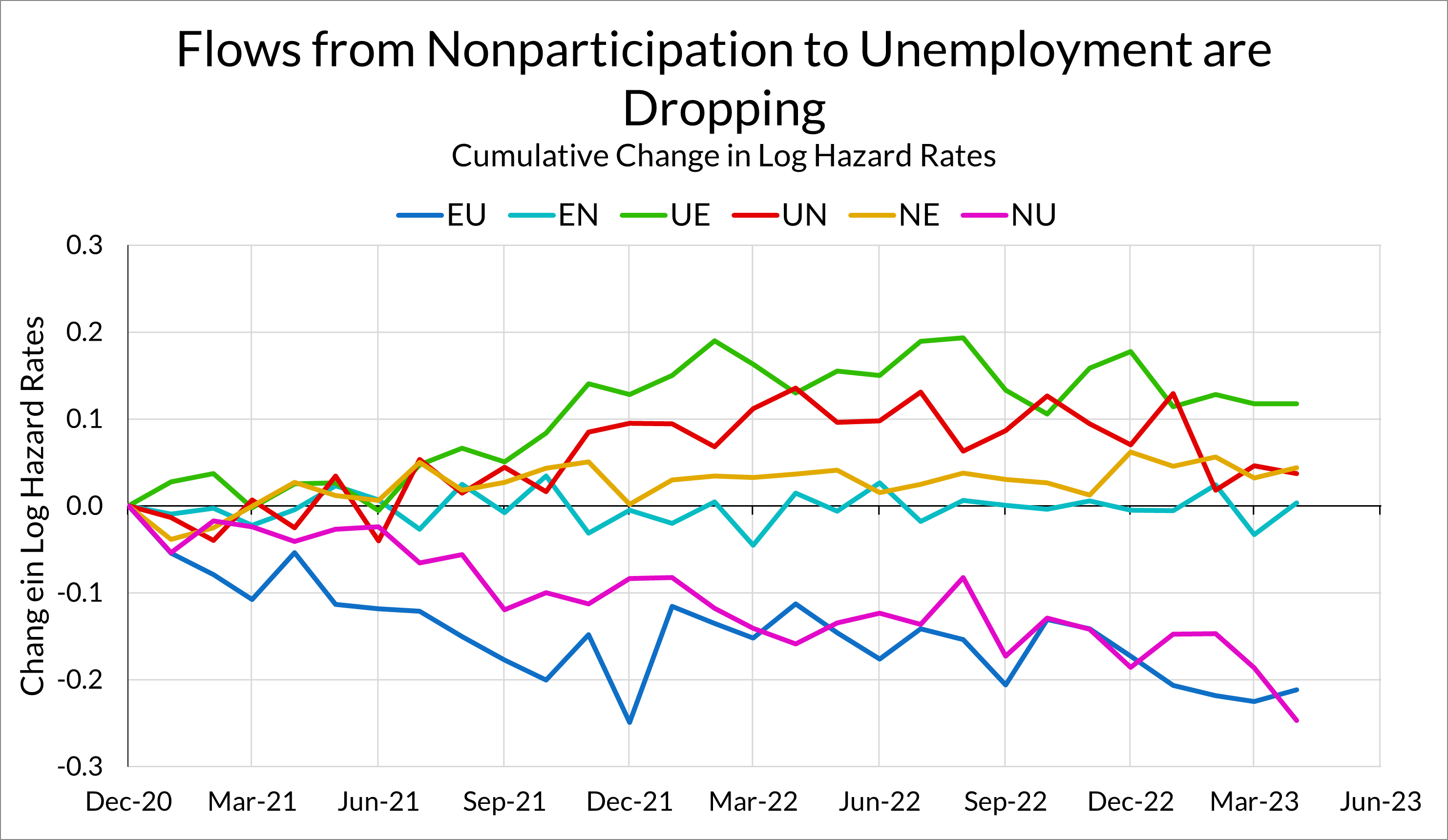

Turning to the flows data, we also do not see any worrying signs of a large increase in the flow rates from employment to unemployment or out of the labor force. The only notable change in recent months is a fall in flow rates from non-employment to unemployment. This is to be expected as employment and participation rise, as the labor market begins to bring in workers that are more marginally attached.

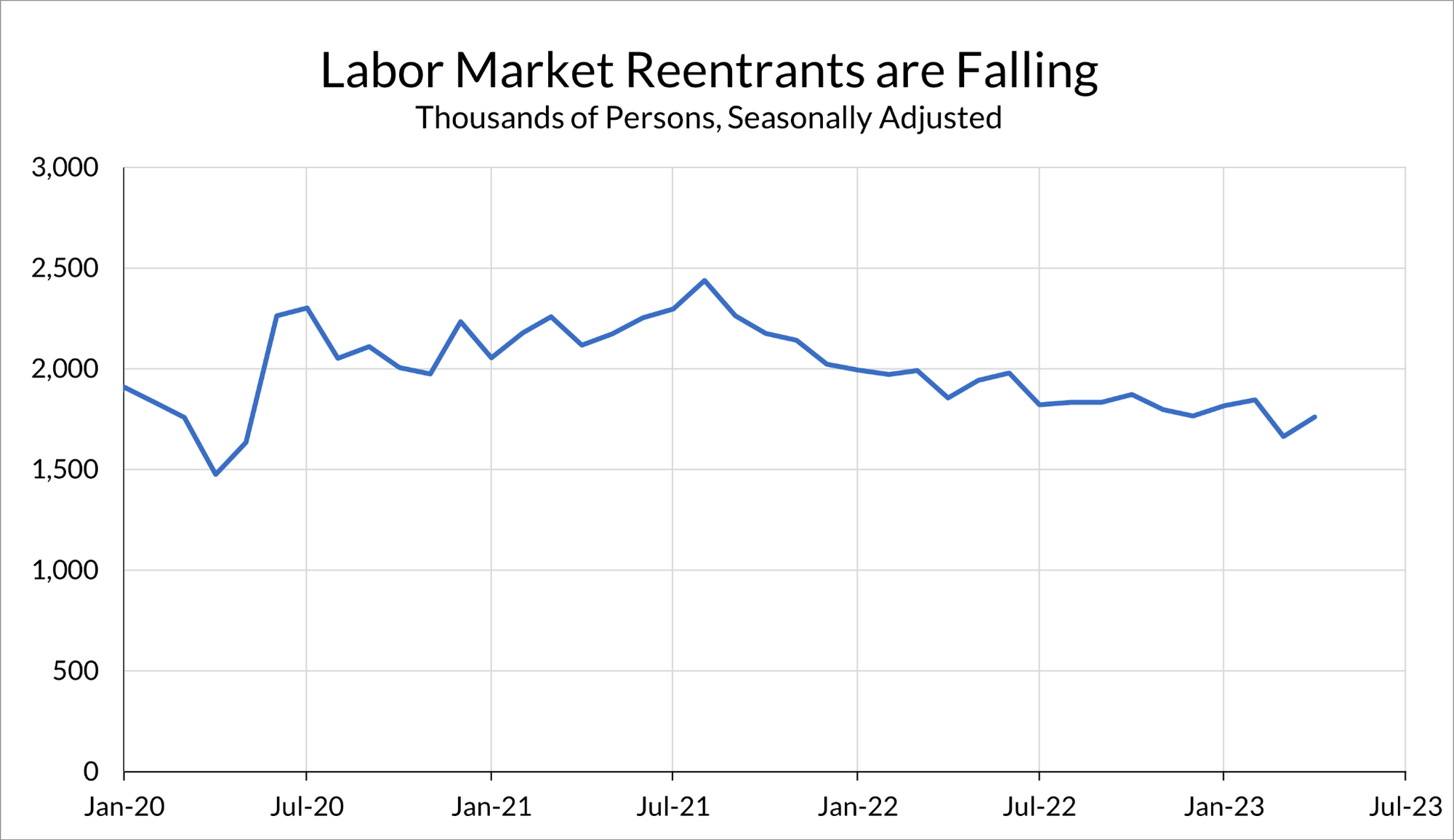

To wit, the number of unemployed labor force reentrants has been steadily following over the past few months. One way to interpret the low unemployment rate is that as employment and participation rises, once the labor market works through workers that are strongly attached to the labor market, such as labor market reentrants, it needs to turn to workers that are less attached to the labor market. This means turning to those out of the labor force who might have been less likely to report themselves as engaging in search activity.

One possibility is that less marginally workers are less likely to consider themselves to be actively searching for a job and unemployed. This would explain why the NU flow rate has fallen and the NE flow rate has increased. The composition of our new labor market entrants is skewed more and more towards marginally attached workers.

Slowing is Possible without Deterioration

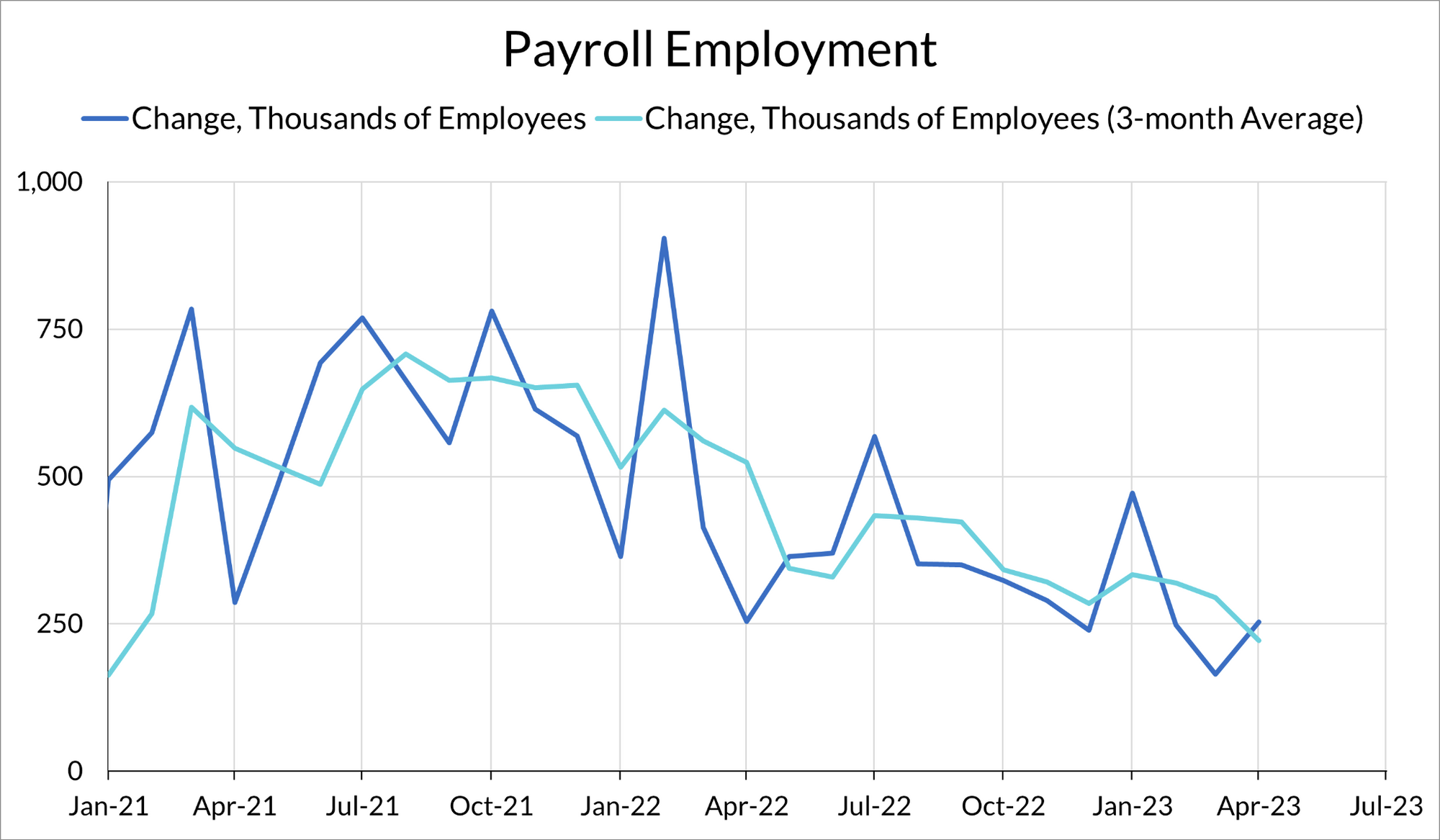

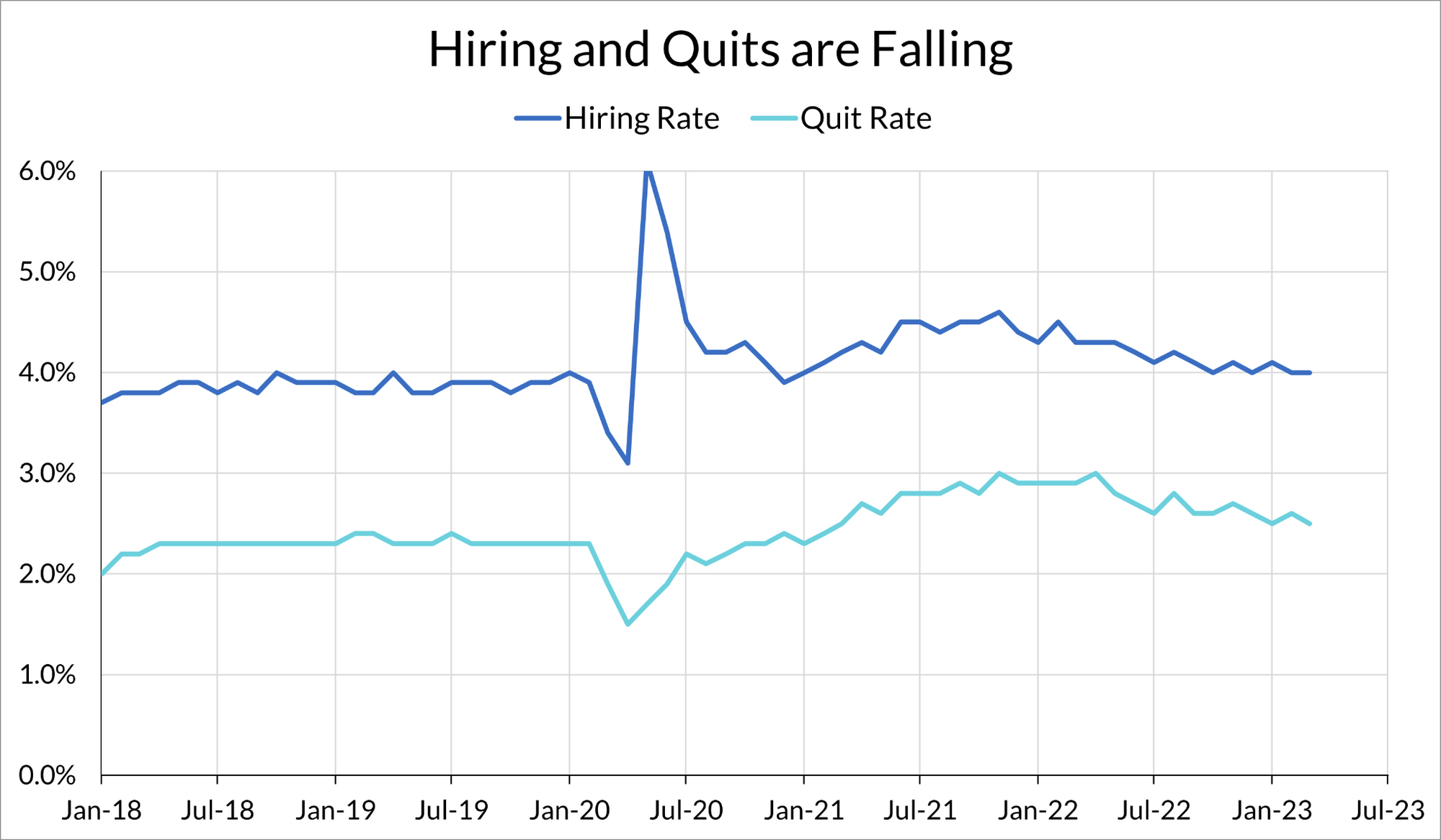

Even though employment levels are strong, it is still the case that the labor market is slowing. Payroll employment growth is still on its bumpy downwards trajectory, and the JOLTS numbers from last month show slowing hiring and quits, with both at pre-pandemic levels.

At this point, the Fed’s projections for 4.5% unemployment by the end of this year look implausible. Getting there would require an extremely rapid increase in the unemployment rate. The Fed is likely to revise its projections of the unemployment rate downwards at the next meeting. For commentators and Fed officials who are relying on a levels-based Phillips curve view of inflation and the labor market, this report calls for stronger Fed action. However, they should recognize that the slowing growth in the labor market, even if levels remain healthy, is itself disinflationary.