The FOMC meeting this week marks the one-year anniversary of the Fed raising the federal funds rate to its current level last July. Since then, inflation has fallen from over 4% to just over 2.5%, and the unemployment rate has risen by over half a percentage point. Due to these developments, we (and others) have been arguing that July is an appropriate time for the Fed to begin normalizing interest rates. Since the June FOMC meeting, Committee members have started laying the groundwork for rate cuts and expressing greater concern about labor market risks.

Still, a cut at the July meeting appears unlikely to materialize. Even though many Committee members have acknowledged that the decline in inflation and softening in the labor market means that an easing in policy is warranted in the near future, there is also a lack of urgency among those calling for rate cuts.

Part of the Committee’s answer to “Why wait?” and “Why not July?” is that they don’t see any particularly dire warning signs in the labor market at this moment, such as a rise in layoffs:

One indication that this is a loosening, rather than a weakening, of the labor market is that layoff rates have been more or less steady at the low rate of around 1 percent.

Chris Waller

I do think that preemptive cutting is something that you do when you see risks but what i see now is a strong labor market that has come into balance

Mary Daly

If the labor market cools too much and unemployment continues to increase and is driven by layoffs, I would see it as appropriate to cut rates sooner rather than later.

Adriana Kugler

In short, while the Committee is getting ready to normalize interest rates as inflation comes down, they’ve rejected preemption of labor market risk (something we argued for in our 2024 Fed Playbook) as a rationale for continuing to wait. The slowdown in hiring (without an observed increase in layoffs) is, to the Committee, not concerning in and of itself. In fact, it is actually a welcome development in rebalancing the labor market.

This strategy amounts to playing with fire. Layoffs, especially as measured by JOLTS, may not be timely enough to be a reliable indicator for when labor market risk is elevated. A decline in hiring activity is historically as damaging to workers as layoffs, and deserves to be taken seriously. Fire prevention—rather than fire fighting—is a better approach to risk management when it comes to the labor market. When it comes to unemployment risk, the Fed should be proactive and preemptive, not reactive.

Layoffs Can be Late to the Punch

A frequently-cited statistic that Fed officials point to when they are downplaying the labor market risks of tight monetary policy is the low rate of layoffs. Despite the increase in the unemployment rate, the rate of layoffs is just below its pre-pandemic level, hovering just around 1% for the last couple of years. In fact, the layoff rate fell below 1.0% in today's JOLTS report, its lowest level since early 2022.

Does the low level of layoffs necessarily imply that the risks to the labor market are low? While it’s always relieving to not see layoffs, it’s not a sure-fire way of assessing the risks to the labor market in real-time. Kugler has acknowledged some issues with the timeliness of the JOLTS layoff data, noting the fact that JOLTS is released with a one-month lag. However, the problem with waiting for layoffs is that layoffs can lag the beginning of labor market recessions even beyond the one-month release lag. The history of the JOLTS layoff data is short, but what we have from its short history suggests that JOLTS layoffs can be late to the beginning of recessions.

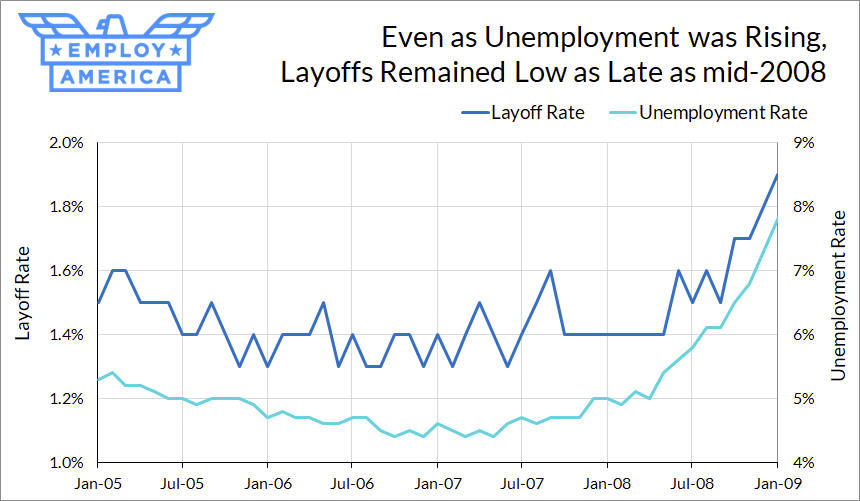

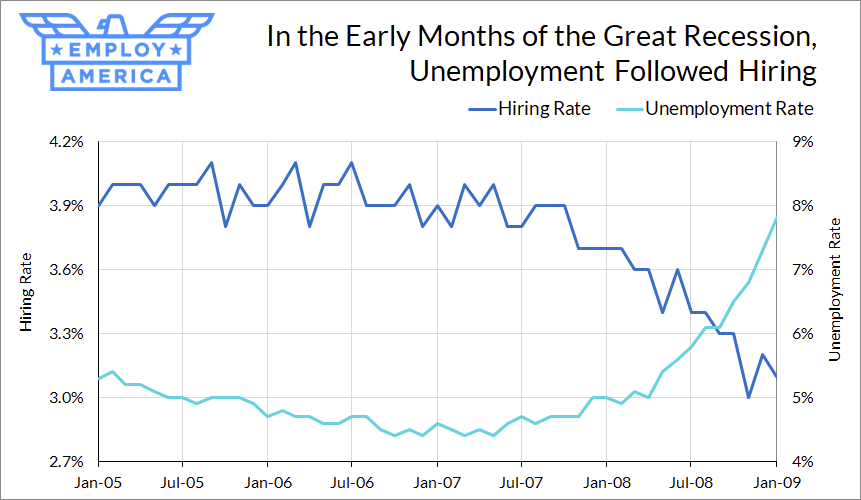

In the run-up to the 2007 recession, it would have been difficult to see the labor market deterioration through layoffs alone. Despite a small blip in layoffs in September 2007, layoffs were relatively flat until mid-2008. Meanwhile, unemployment was rising.

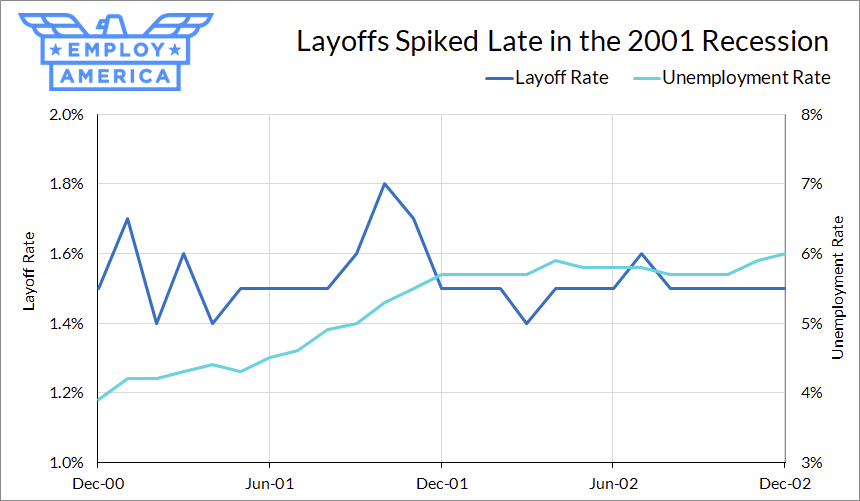

The same is true for 2001; while we don’t have much data for the months leading up to the 2001 recession, the spike in the layoff rate appears to happen in the latter half of the recession, even though unemployment was rising beforehand.

To be fair, Fed officials have pointed to other indicators they are looking at to help predict labor market risks. Kugler, for example, said she is looking at alternate Challenger and WARN layoff data to deal with the JOLTS data lag. However, this may not be enough; while researchers have found that WARN data do appear to provide some advanced notice to JOLTS layoffs, the lead time is only one or two months (WARN notices are only required to be issued 60 days before layoffs).

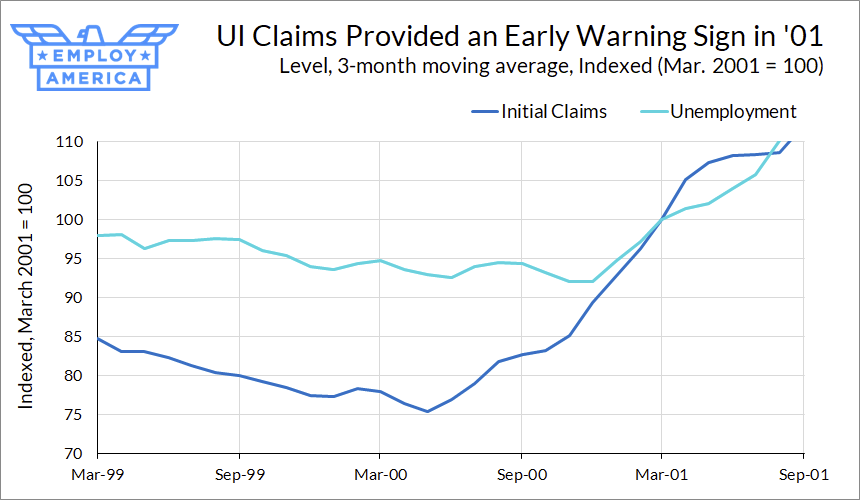

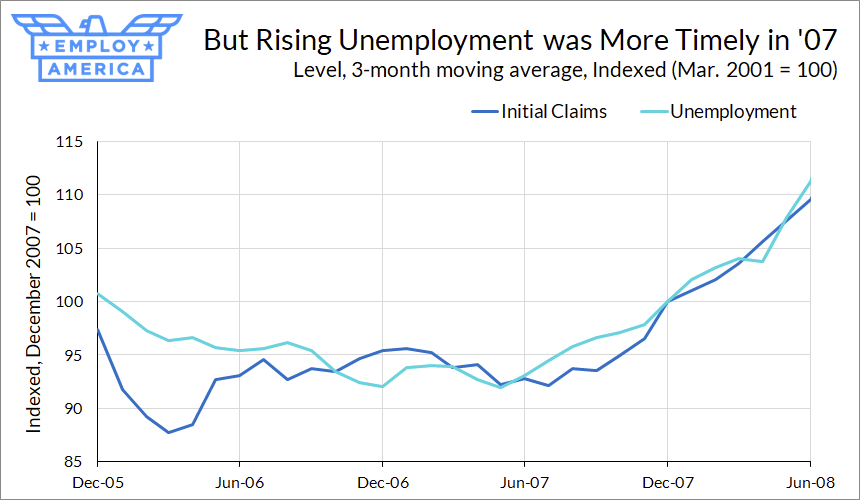

Alternatively, Daly says she is keeping an eye on unemployment claims as a canary in the coal mine. While unemployment claims have provided an early signal of incoming labor market stress in some instances, such as in 1990 and 2001, this signal is also not foolproof. By the time the rise in initial claims was apparent in 2007, unemployment had already been rising for months.

Falling Hires is a Problem

If layoffs aren’t a reliable timely indicator of labor market stress, that means hiring deserves more attention. We’ve previously written about how the bulk of net job loss over the course of recessions operates through declines in the hiring rate, but there are times when hiring may prove a more timely signal than layoffs. Turning once again to the Great Recession, the decline in hiring was clear by early 2008, earlier than the rise in layoffs.

Looking at the transcripts from that time, the Fed saw the softening in the labor market as primarily stemming from a decline in hiring rather than layoffs. This may have been one reason why the Fed failed to fully appreciate the full scale of the recession they were about to face.

The slowing that we have seen thus far in employment growth has come more from a slower pace of hiring than it has from an increase in layoffs.

David Stockton, Board of Governors Associate Economist, January 2008 FOMC Meeting

One FOMC member that is taking heart in the fact that labor market softening has so far come from lower hiring activity rather than firing is Governor Waller. This view can be traced back to his work on the Beveridge Curve, where he argued that a path to a soft landing could be achieved through a decline in vacancies if layoffs were to remain low. One of the key arguments in his note was that absent an increase in separations, the Beveridge Curve was relatively steep. The implication of this was that a decline in vacancies (the main mechanism that drives hiring in the Beveridge Curve model) would be unlikely to result in a large increase in unemployment.

Unfortunately, that view is inconsistent with the movements of hiring and layoffs during the Great Recession. While the labor market did experience a spike in the layoff rate throughout 2009, the layoff rate fell to pre-GFC levels by 2010, when unemployment was still above 9%. Unemployment then gradually fell to 3.5% throughout the 2010s, despite the layoff rate only falling slightly throughout that period.

In other words, as recently as the last decade, we were on the flat portion of the Beveridge curve even without an appreciable change in the layoff rate.

Fire Prevention is a Better Strategy than Firefighting

If there’s one takeaway from the data, it’s that no one labor market indicator provides a reliable forward indicator of an imminent increase in unemployment. This might be an unsatisfying answer, but it makes a lot of sense. If hires fall or layoffs rise, those are likely to show up in overall unemployment anyways. And when unemployment rises to recessionary levels, it tends to do so quickly.

This poses a problem for monetary policy that is aiming to keep us out of a recession: you get very little warning when the labor market is about to break, and when it does, unemployment rises quickly. If you wait for the obvious signs that things are rotten in the labor market before acting, it is likely to be too late.

In light of this, we think the Fed should take a different stance towards labor market risk: the Fed should be proactive and preemptive, not reactive. Fire prevention is more effective and less risky than firefighting. We are by no means saying that a recession is imminent. There are ample reasons to discount the recent rise in the unemployment rate, but that doesn’t mean the Committee should sit on their heels when it comes to unemployment risk.

Given how much inflation has fallen, the Committee should feel like it has room to begin cutting to recalibrate policy. A cut at the July meeting would still leave rates at restrictive levels relative to standard monetary policy rules. Committee members, including many of those quoted in this piece, have acknowledged that the balance of risks has shifted—the federal funds rate should shift in response.