Introduction

On Friday, the Biden Administration announced that its October solicitation for crude oil had successfully closed with the acquisition of 2.7 million barrels of oil for delivery in January 2024, while simultaneously announcing a new 3-million-barrel solicitation for delivery in February.

When DOE announced its strategy to open solicitations at a fixed price monthly till at least May, it was met with considerable skepticism. However, since peaking at around $93 per barrel at the end of September, crude oil prices have been on a decline the past two months, settling into a range of $72 to $75.

By stating that they would purchase up to 3 million barrels per month at a price of $79 or below, the announcement amounted to a rolling, open put option till May. Even amidst the tight market, we applauded the decision, noting that while “it’s possible [it] ends up with no actual acquisition,” it’s a positive step to “developing the internal capacity to do more creative, long-term acquisition.”

Now, as prices have fallen, DOE has demonstrated that creative, market-friendly forms of acquisition can work. Specifically, DOE demonstrated a few critical competencies:

- The DOE has shown that it can manage multiple solicitations at once. When the plan was announced in Oct., DOE announced two simultaneous solicitations for December and January.

- The DOE has shown that it can announce a long-term commitment to purchase—when the solicitation was announced in October, DOE bound its hands till at least May 2024.

- By setting a predetermined bid price of $79, the DOE has shown it can acquire crude in a manner that offers marginal–albeit highly limited–optionality to producers. If market conditions warrant acquisition, then great, but if not, no harm no foul, and DOE could acquire at another time.

In sum, by successfully acquiring crude in this fashion, DOE has demonstrated that it can creatively adapt its processes to acquire oil in a thoughtful and market-friendly manner.

Now, DOE can capitalize on its capabilities and the current slack market to acquire as much crude as possible for the SPR. Deputy Secretary of Energy Dave Turk recently said that the agency would purchase back “as much [oil] as we possibly can.”

This is a welcome development. DOE should capitalize on this opportunity to stabilize the market by executing fixed price contracts for 2025 delivery while continuing its open solicitation for purchases.

Constraints

Optimal fixed-price forward contract execution will require thoughtful planning and consideration of the challenges associated with long-term acquisition. Although the major barriers are logistical, there are also financial and market considerations.

Logistical Constraints

As we’ve previously written, there are logistical constraints to managing SPR acquisition effectively.

First, DOE cannot simultaneously acquire and release barrels from the same site. Any months where DOE expects to release - or at least would like to maintain that flexibility - would be off-limits for acquisition delivery. That might happen during hurricane season, for instance, where DOE has previously provided supply when Gulf Coast operations break down. Given the volatility in oil prices over the past two years – and the prospect of further geopolitical disruptions – DOE should strive to maintain that flexibility in the event of major disruption.

Second, DOE must consider ongoing maintenance operations intended to safeguard the long-term health of the reserves. DOE often voices the need to “prioritize the operational integrity of the SPR, to ensure that the SPR can continue to meet its mission as a critical energy security asset.” This means ensuring the SPR’s infrastructure can still perform its core functions in the event of an emergency.

To this end, the Life Extension-II project (LE-II) is its largest effort to increase the life of the asset. DOE has planned numerous activities in accordance with its LE-II plan, including contractually obligated construction projects. In 2024, the West Hackberry site is likely to undergo significant construction and maintenance activities, and at least another six “major maintenance construction projects” are planned for other sites. In 2021, DOE approved the start of construction activities for the Bryan Mound, Big Hill, and Bayou Choctaw sites (the most recent solicitations have all been to Big Hill). The emergency sales in 2022 delayed necessary construction in Bryan Mound and Bayou Choctaw. As it stands now, it seems that Bayou Choctaw construction is proposed to be completed by January 2025, leaving it open for acquisition throughout 2025 (unless of course if plausible delays occur). Big Hill and Bryan Mound are likely to have maintenance activities ongoing through 2025.

Finally, DOE already needs to manage incoming deliveries of exchange returns, with just over 23 million scheduled to be returned in 2024, and at least another 3.5 million in 2025, per our calculations. Given intake capacity constraints, these exchanges will limit the possibility of other acquisitions. These exchanges were previously scheduled for 2023.

Financial and Market Constraints

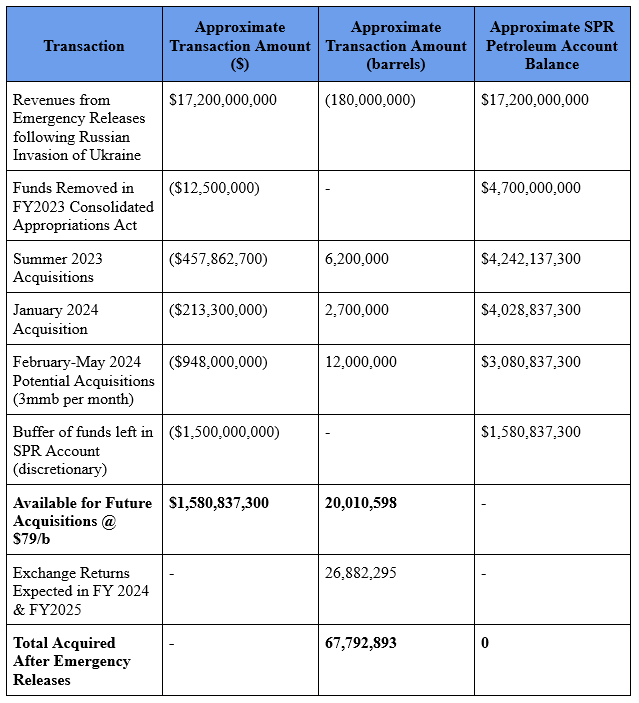

Last year’s releases generated just over $17bn for the SPR account which could have been used for future purchases. However, Congress raided the account to pass the omnibus in December 2022, leaving just $4.7bn for future acquisitions.

While it’s a considerably lower sum and makes a complete refill impossible, it’s still enough to purchase a lot of oil. After accounting for the 6.2MM barrels purchased in the summer of 2023, the 2.7MM barrels recently acquired for January 2024 delivery, and the possible additional purchases of 3MM barrels per month till May as part of the new repurchasing program, DOE would have over $3bn available in its petroleum account. It would obviously not be wise to spend all of its resources, but even if DOE wanted to keep $1bn to $1.5bn in its account for future acquisitions, the agency could conceivably contractually obligate the acquisition over 20 million barrels in 2025, for a total of 40 to 60 million barrels since the end of 2022. Combined with returned barrels from exchanges, DOE could plausibly contractually fill a third to nearly half of the 180 million released. For reference, the last refill from current levels took place in 1983 (when physical acquisition was much easier), and it took four years to fill the SPR to 530mn (its level in early 2022).

Just twelve to twenty-four months after the last release, DOE would be well on its way to replenishing the oil released in the wake of the Russian invasion, a laudable achievement and one that would justify future appropriations to fully complete the refill.

Proposal: Pair The Existing Solicitation with Long-Term Forwards

To maximize acquisition in our current price environment, we recommend that DOE pair its existing open solicitations through May with long-term forward fixed-price contracts for delivery throughout 2025. While the constraints are challenging, they do not completely tie DOE’s hands on acquisition. Two critical realities make this possible: (1) the ability to conduct fixed-price forward contracts that allow DOE to separate financial settlement from physical settlement; and (2) relatedly, DOE’s considerable explicit and incidental contractual powers to navigate the complicated set of constraints it faces.

Given the logistical constraints for 2024 from incoming barrels, maintenance under the Life Extension II program, and purchase commitments already till at least May, additional acquisitions through 2024 may be difficult. However, DOE could lock in contracts now for 2025 delivery and still protect itself against logistical and other forms of risk. As we established earlier, DOE has the resources available to lock in a significant number of barrels in the future.

A roadmap to doing so requires planning. First, establish a fixed number of barrels that DOE wishes to acquire through long-term forward contracts. With the $1.5bn buffer we established earlier for emergency acquisition or other purposes, DOE can acquire at least 20MM barrels through long-term forward fixed-price contracts, while continuing its ongoing short-term solicitations.

With the size of forward acquisition settled, DOE can navigate the logistical challenges of managing these contracts. We suggest a twelve-month period, between January 2025 and December 2025.

Removing the worst of hurricane season leaves around ten months for delivery. Within those ten months, it’s possible that more Life Extension II projects will move to construction stage, that DOE can’t anticipate exactly when that will be given both bureaucratic timelines that involve private contracting, or that planned construction projects get delayed. Here’s where the physical and financial delivery distinction matters: DOE can manage these risks with extended delivery periods.

DOE could designate a three-month, or even a six-month physical delivery period, at its discretion (with a pre-established date by which DOE must determine the delivery date). Although most of its recent solicitations have specified a one-month delivery period, in its July 2023 solicitation, DOE specified a delivery period of two months, so a multiple-month period for delivery is possible.

Contracts would still be financially settled at the designated month, but delivery would be more open. Of course, producers would charge a premium for this flexibility. The fact that 2025 is still over twelve months away is critical because the cost of that premium will be much lower given that they can hedge their exposure much more easily. In our current price environment, with WTI Jan 2025 futures at $72 (and decreasing to $68 by the end of 2025), DOE would still likely receive a price under its $79 threshold.

Flexibility is also important when the DOE looks to manage the risk associated with the market and global events. DOE has the incidental contractual authority to cancel delivery if conditions warrant. While DOE might be reluctant to invoke this authority and cancel contracts with private parties—given the circumstances under which this would be necessary—cancellation would likely result favorably for the producers. Extreme disruptions in supply would invariably result in prices higher than the fixed price of $79—producers would likely be able to get a better price on the open market. So while utilizing the authority to cancel might seem to send a poor signal to market participants, in fact it would be a strong signal that DOE is acting in a market-friendly manner that aligns with producer incentives.

The real analogue to fixed price contract deliveries for the DOE, though, is the management of exchange returns, which are open and have been rescheduled in the past. After the first part of an exchange (the release), the return works just like a forward contract for acquisition—open-ended and subject to change if conditions warrant. If DOE can manage that, there is simply not a distinction great enough that should make managing long-term forward contracts impossible.

Following a successful pilot of a long-term forward fixed-price contract, perhaps after multiple solicitations to get the mechanics right, DOE should use this moment to lock in as many barrels as possible for delivery in 2025.

Conclusion

Amidst flagging oil prices, if DOE can successfully acquire approximately 40 to 60 million barrels, in addition to the nearly 27 million exchange barrels incoming in 2024 and 2025, it will have refilled at least a third to nearly half of the release resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and its disruption to the oil markets.

That’s responsible. By building important capabilities for acquisition in a manner that protects domestic consumers and producers while ensuring a taxpayer return, DOE would be well equipped to seek more funding for future acquisitions to refill the full amount and maintain the long-term strategic security of the SPR.