As we await the Q4 Employment Cost Index (ECI) release tomorrow (forecasting consensus: 1.2% QoQ, 4.9% CAGR; Q3: 1.2% QoQ, 4.8% CAGR), two key points to keep in mind.

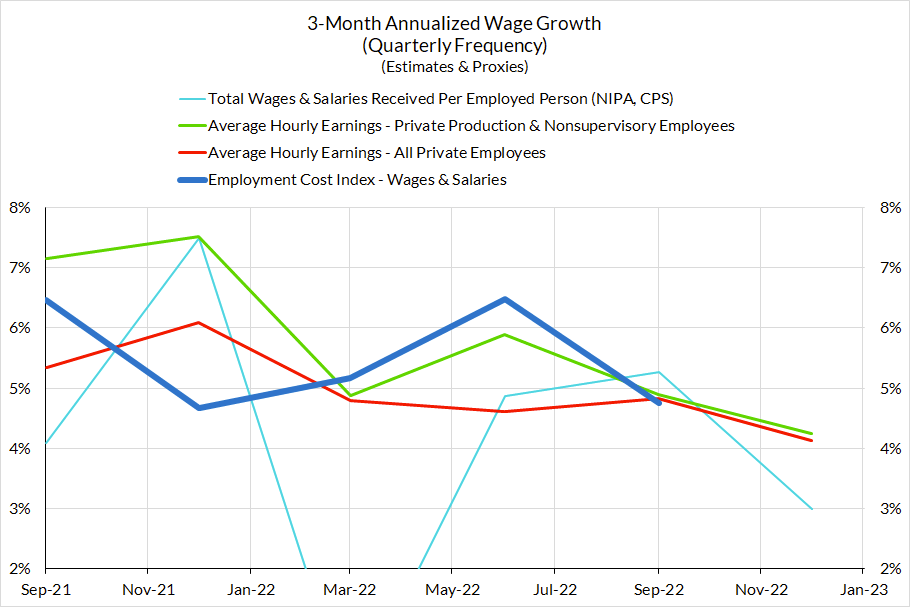

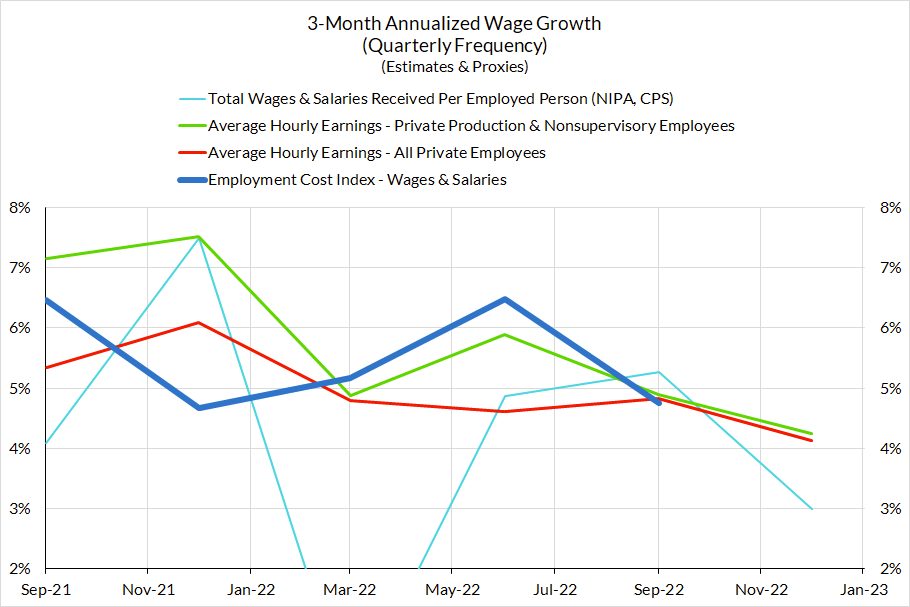

- The Q4 Data Showed Slowing Across Many Wage and Wage-Relevant Indicators, Potentially To 4.2% annualized. From September to December, we saw further (1) slowing average hourly earnings, (2) slowing gross labor income (and per employed person), and (3) slowing consumer spending.

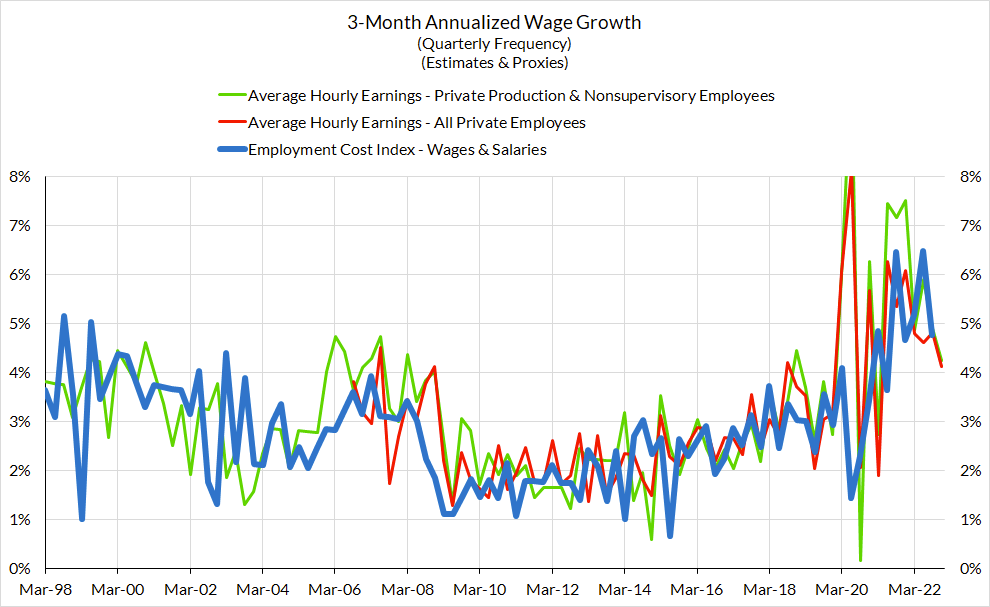

- ECI is still quite noisy and prone to lagging underlying labor market dynamics. ECI can still diverge substantially and lag fundamental economic dynamics. Given the scale of sectoral reallocation post-pandemic, ECI may be more vulnerable to lags now.

Actual Economic Implications: A number of measures of nominal income and spending growth are already confirming a normalization back toward pre-pandemic growth rates. This basic fact should soften the urge to panic about the inflationary implications of an upside ECI surprise.

Fed Implications: The Fed's wage-cost-push view of inflation makes ECI a more high-stakes release now than it otherwise should be.

- Should we see more deceleration for Q4, the Fed would probably be more inclined to shade down their expressed need for higher unemployment, and become less concerned about "Core Services Ex Housing PCE."

- Should we see acceleration for Q4, the Fed seems likely to double-down strongly on the importance of higher unemployment and the risks to "Core Services Ex Housing PCE." Needless to say, we disagree with these prescriptive views.

Tomorrow's Employment Cost Index number plays an outsized role in labor market assessments, both for the Fed and for ourselves (albeit for different reasons). Among the government-provided measures of wage growth, ECI has the fewest blindspots and biases for the purpose of real-time business cycle interpretation.

To start with, the data is generally showing a slowing pattern in Q4. Dividing aggregate labor income by total employment or hours worked is vulnerable to composition biases. These measures of "average wages" are far from optimal when making business cycle judgments, but these composition biases should be less aggressive for 2022Q4 (in comparison to periods of recession and rapid recovery). Taken at face-value, annualized ECI growth would be on track to decelerate close to 4.2% annualized in 2022Q4.

But the longer history of ECI give ample reasons for caution when engaging in such crude nowcasting heuristics. There can be substantial divergences between each of these measures in any given quarter.

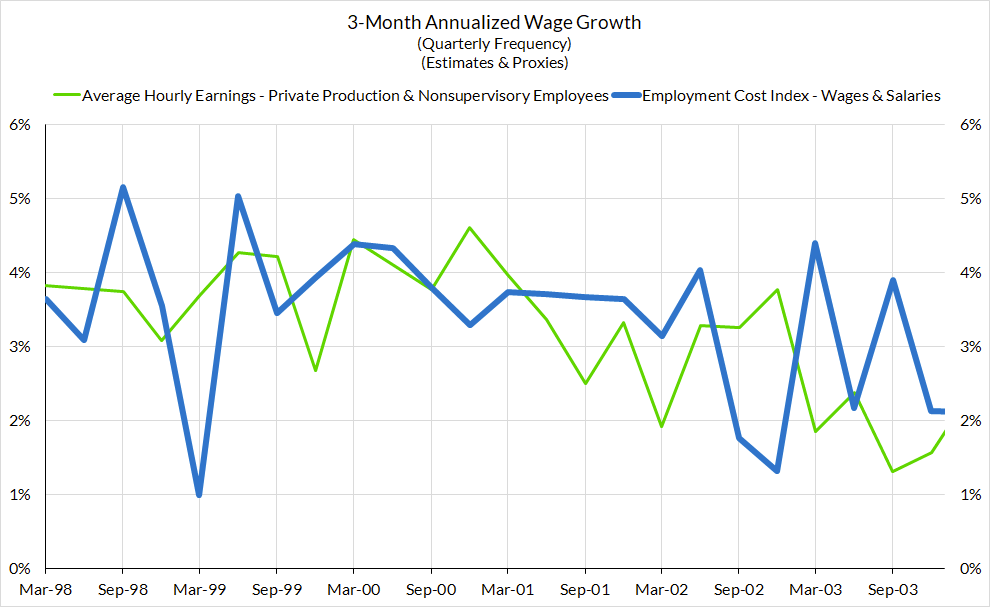

Look closely at the 2000-2002 period and you'll see that ECI growth was especially sticky in the face of underlying economic and labor market deceleration that was transpiring.

With all of these factors in mind, it is best to be prepared for surprises on both sides of the forecasting consensus. And the biggest risk stems from Fed misinterpretation and overreaction to an upside surprise.

- For us, the deceleration in gross labor income growth (which is more easily measured than wage growth and more relevant to inflation) is already showing the case for Fed tightening is diminishing. That we are also seeing slower nominal consumer spending growth adds further confidence to our assessment.

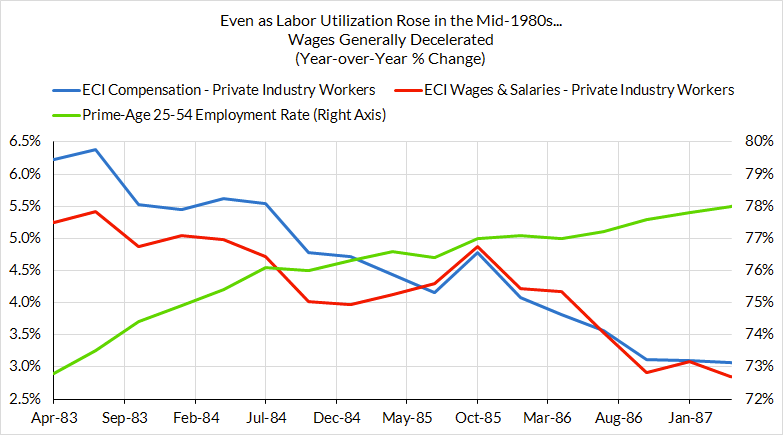

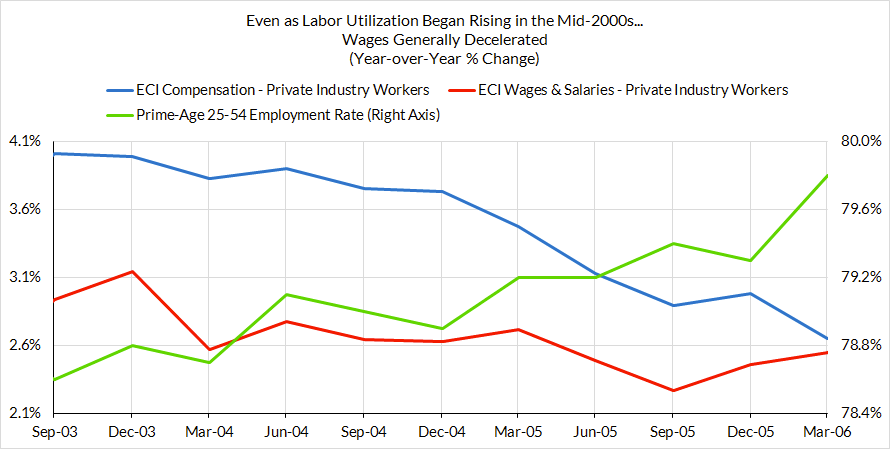

- For the Fed, the wage Phillips Curve still plays a major role in their interpretation of wage growth. In the absence of observed wage deceleration, the Fed will emphasize their belief that "Core Services Ex Housing PCE" is caused by higher labor cost growth and vulnerable to staying elevated as a result (we are skeptical of the premise). More worryingly, the Fed would then be more inclined to double down on the push for recessionary unemployment increases this year. As we have noted before, wages have decelerated in the absence of a rise of the unemployment rate and their growth now does not necessitate aiming for more outright joblessness. See the mid-1980s and mid-2000s for two clear-cut episodic examples.