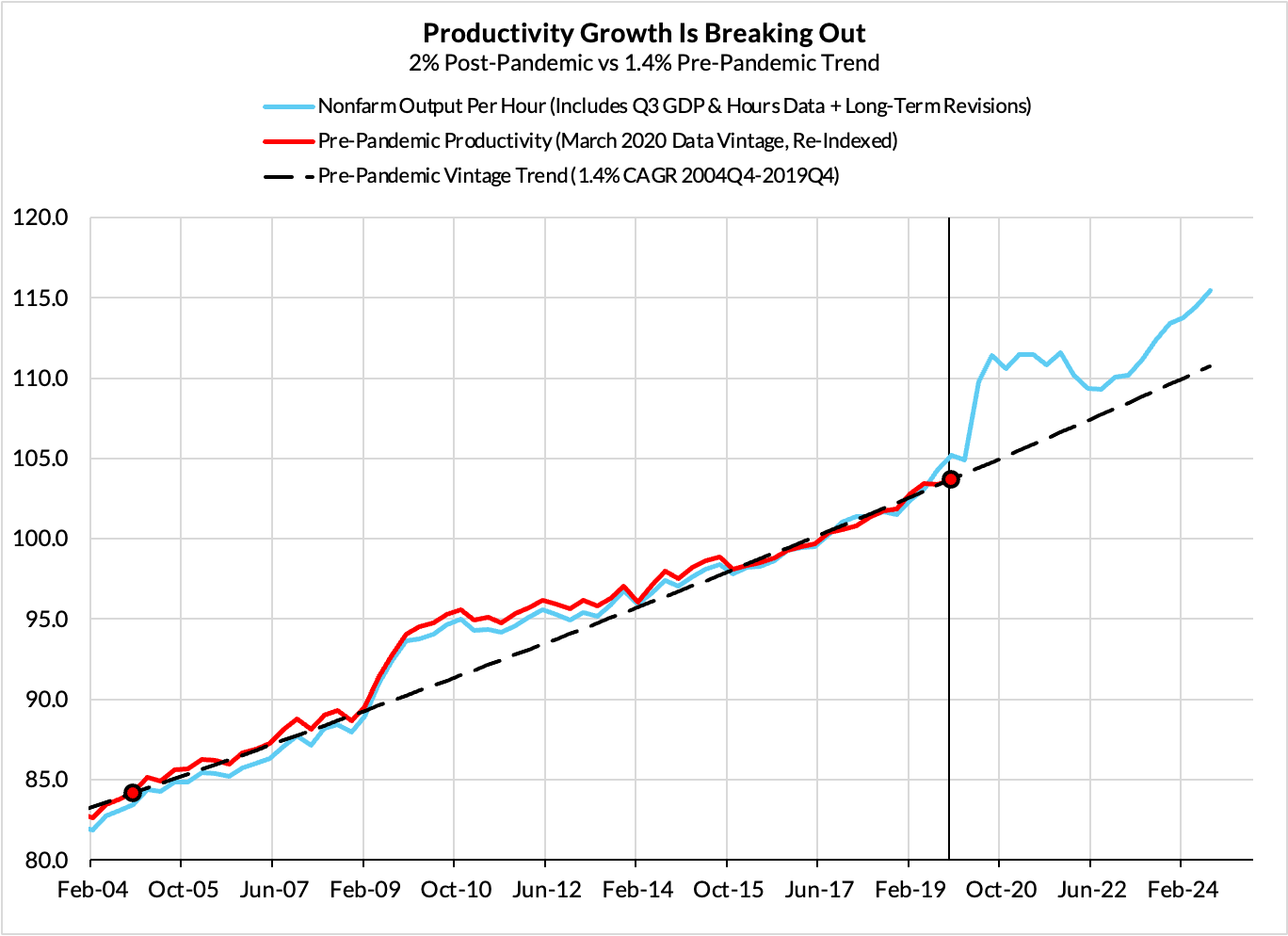

After taking into account data revisions and the Q3 GDP release, productivity growth is running stronger in the post-pandemic period, at about a 2% annualized pace. This stands in contrast to the sluggish ~1.4% pace observed in the pre-pandemic period. We've been productivity optimists for some time now; the downsides of 2022 were never as fatal as they seemed and there was underrated upside earlier last year that has now realized. The combination of (1) full employment, (2) robust industrial fixed investment, and (3) healing supply chains is delivering impressive productivity growth. Prior to the pandemic, few forecasters or commentators thought this kind of breakout from stagnation could feasibly sustain, but the past few years suggest scope for greater optimism.

Summary

As of 2024Q3, post-pandemic productivity growth appears to be running at a 2% annualized pace, markedly higher than the ~1.4% growth rate observed prior to the pandemic. Productivity is volatile and we wouldn't be surprised to see some hiccups in the coming two quarters due to one-off factors, but even so, the performance over the post-pandemic period has sustained long enough for economists to start taking more seriously.

If we just looked at the most recent productivity release from September 2024, we would only see a 1.6% annualized growth rate in the post-pandemic period. However, that data release misses important facts that will only be fully accounted for in March 2025. These facts add an additional 0.3-0.4% to the annualized rate of post-pandemic productivity growth.

- In 2024Q3: Nonfarm business output grew at a 3.5% annualized pace even as hours worked grew at a 0.2% annualized pace.

- This implies an impressive 3.2% growth rate in productivity on an annualized basis in Q3. We should see something close to this estimate next week.

- Long-term GDP revisions last month added an additional 1.3% to post-pandemic nonfarm business output. These revisions should be incorporated next week.

- The preliminary benchmark employment revisions for March 2023 to March 2024 suggest hours worked in the post-pandemic period was 0.5% lower. These revisions will be incorporated in March next year.

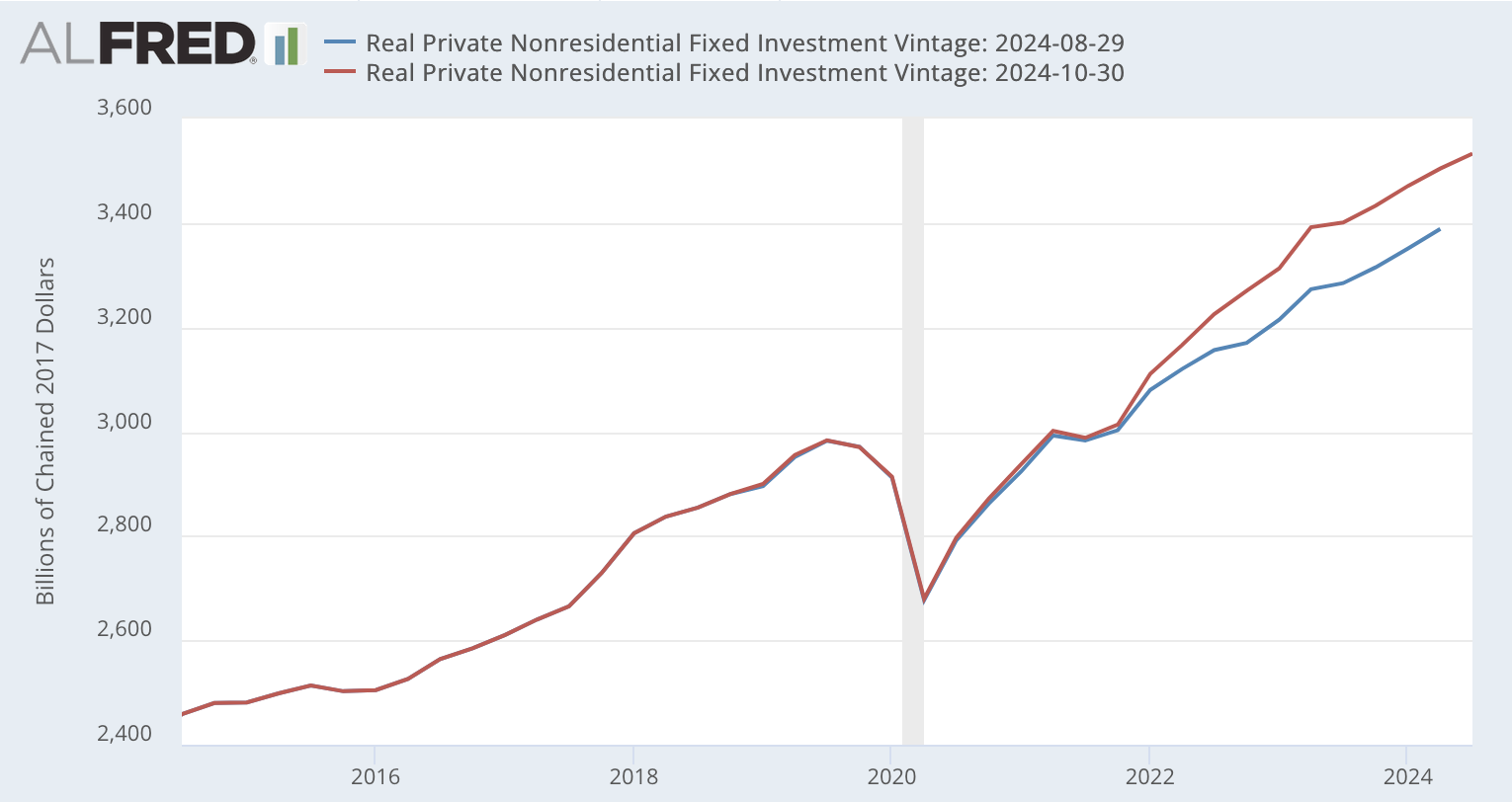

In our view, this outperformance can be chalked up to three facts:

- Full employment conditions—in which more workers have already been hired and trained up with relevant experience—promote greater expansion of real output for a lower level of growth in hours worked.

- Public policy supports for fixed investment has allowed it to run at the pre-pandemic trend despite headwinds from sectors sensitive to higher interest rates. Both direct public investment efforts and certain tax provisions have helped crowd-in private fixed investment and keep it resili.

- Supply chain healing—as critical sectors have de-bottlenecked and commodity prices have largely stabilized—has meant that a given dollar of consumer spending is less inflationary now than it was 2-3 years ago, and is now more likely to support additional real output instead.

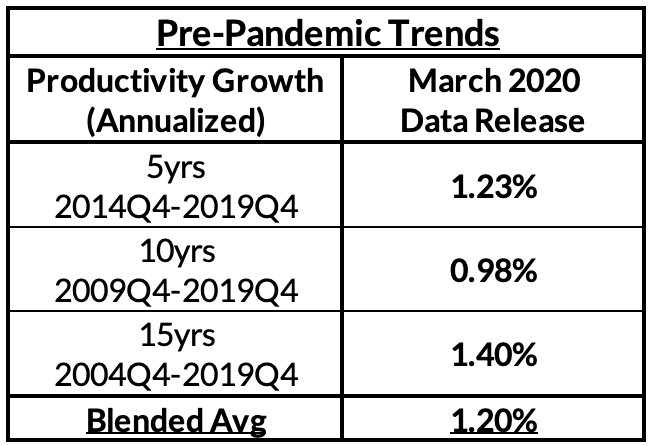

A Full Employment Economy Continues To Be A More Productive Economy

We continue to see that the high level of prime-age employment in the past few years is translating, with a modest lag, into higher productivity growth. If we look beyond the periods in which productivity is distorted by recessions, the level of prime-age employment can explain as much as 35% of the variation in productivity growth. That still leaves plenty left unexplained, but for a macro variable that is notoriously hard to make full sense of, a solid fractional explanation is worth taking note of.

Every 1% improvement in the prime-age employment in the United States seems to coincide with about 0.4% better productivity growth on average. At a a time when prime-age employment has been above 80% consistently, achieving above-trend productivity growth outcomes is actually not all that surprising.

There are at least three relevant mechanisms for how full employment can support productivity:

- Experience pays dividends: Workers with longer durations of employment, training, and experience could support faster real output gains, without requiring proportional increases in hours.

- Consumer spending growth is less dependent on job growth: As wage growth rises in a tighter labor market, the source of nominal and real demand growth is less directly tied back to job growth. Of course, there still needs to be real supply to match real demand.

- Labor-saving capital expenditures: To the extent firms view labor as scarce or expensive, it may encourage more investments in automation. This is the explanation people tend to be most fond of, but we would warn that it is only more episodically true. Based on what we see, it is less obviously relevant right now relative to the first two mechanisms.

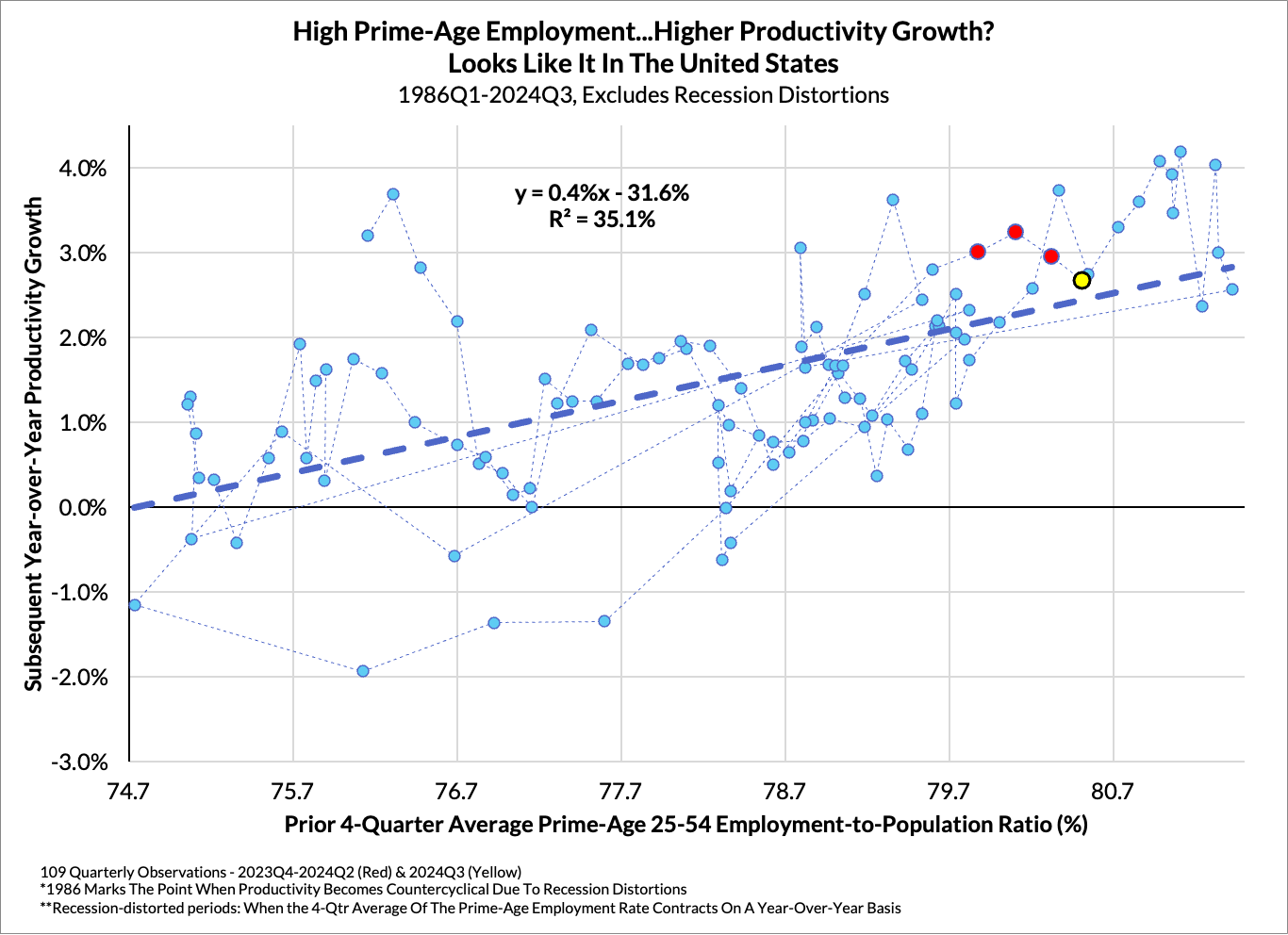

GDP Revisions Now Show That Investment Has Defied Fed Tightening. Fiscal Policy Has Likely Helped

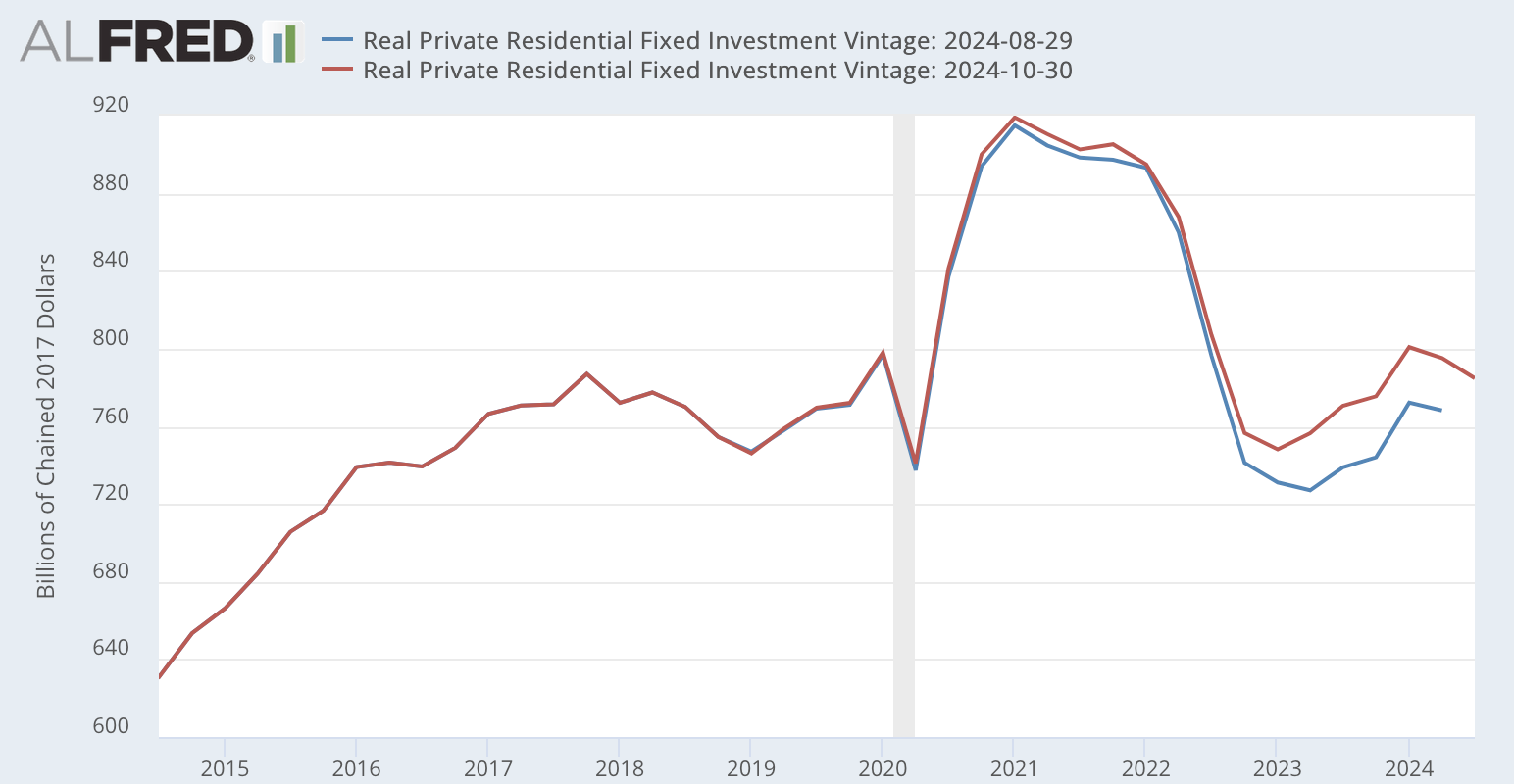

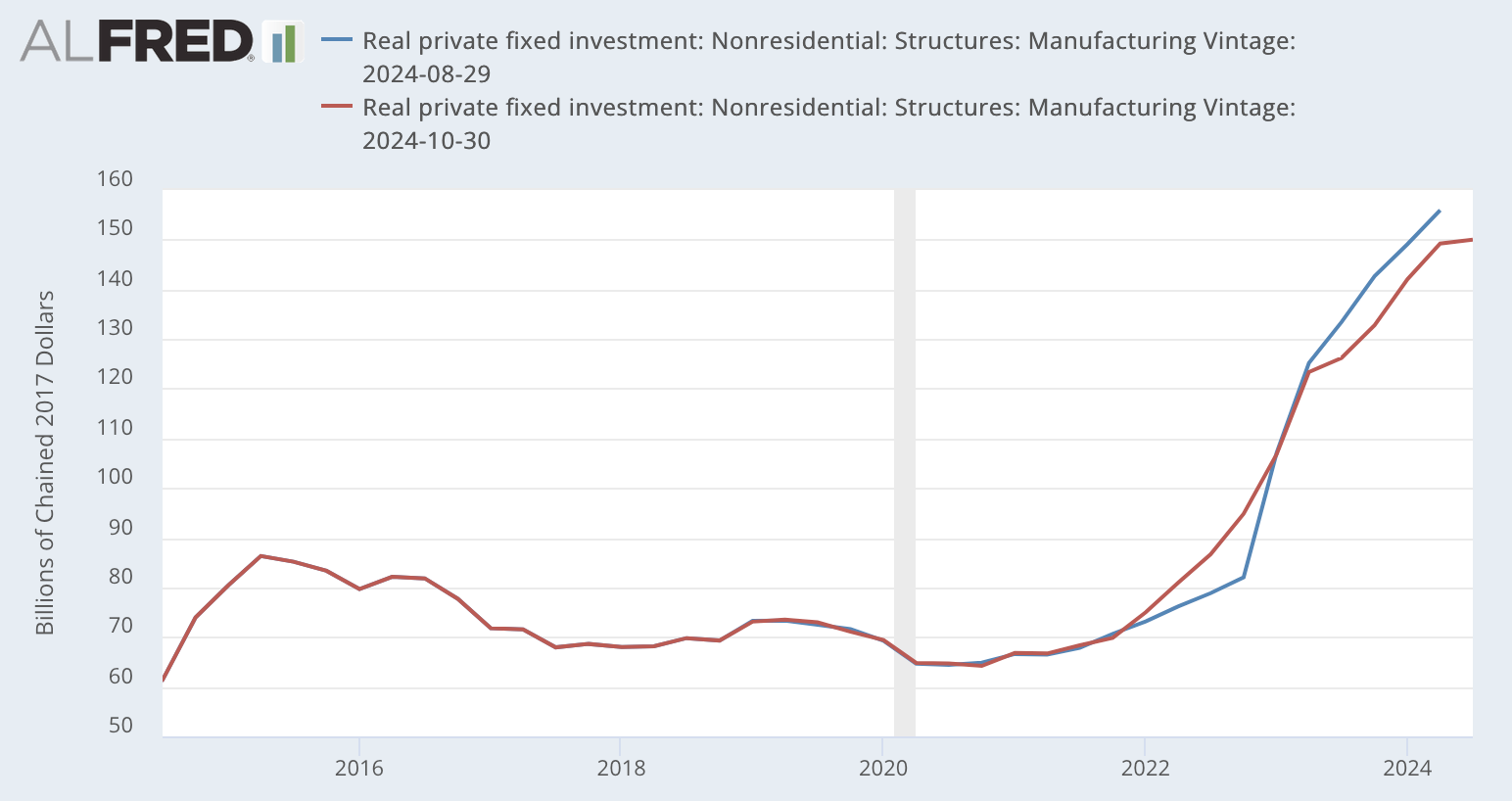

Despite the Fed clearly depressing housing (residential fixed investment) and other interest rate sensitive sectors, the latest batch of GDP revisions in September now show that aggregate fixed investment appears to be running at its pre-pandemic trend. Upshot: for sectors with investment decisions less sensitive to interest rates, investment is outperforming pre-pandemic trends.

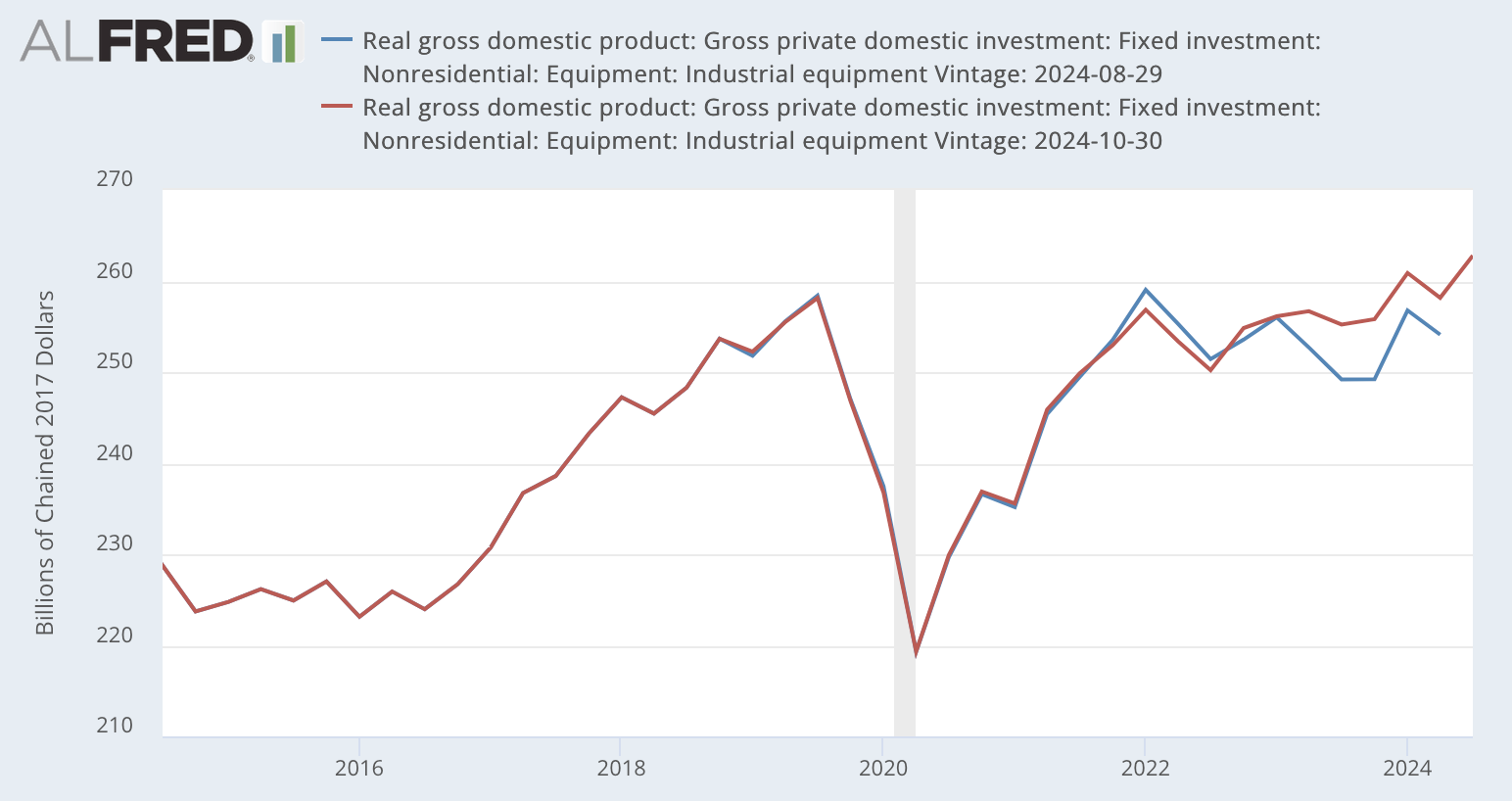

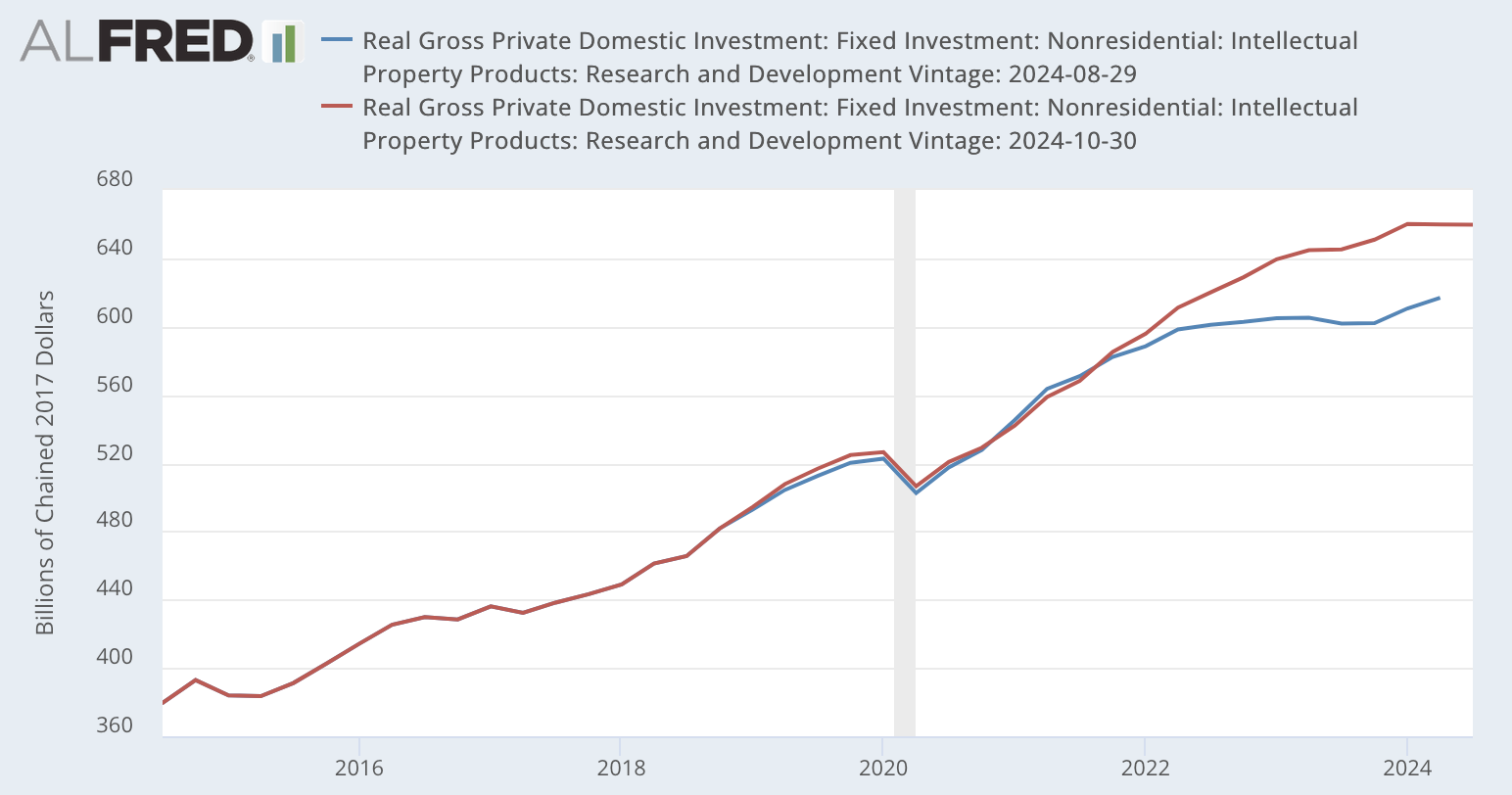

Fixed investment gains appear to be strong in some key policy-adjacent categories, but also with decent breadth, implying (1) that concentrated public investments (and investment supports) are having meaningful crowding-in effect, and (2) certain TCJA provisions have been a more helpful tailwind than previously appreciated.

Real investment in manufacturing structures (factories) has been an obvious standout, doubling in the past 3-4 years. The surge in investment here is specifically for the future production of (1) computers, electronic products & components, and (2) electrical equipment, appliances & components; all other manufacturing subsectors are far less relevant to this surge. Products in the relevant segments here are also those that CHIPS and IRA have actively sought to spur (semiconductors, solar panel components, batteries, electrical equipment). It's worth noting that this boom has, on its own, largely offset the downside impact stemming from housing and higher mortgage rates.

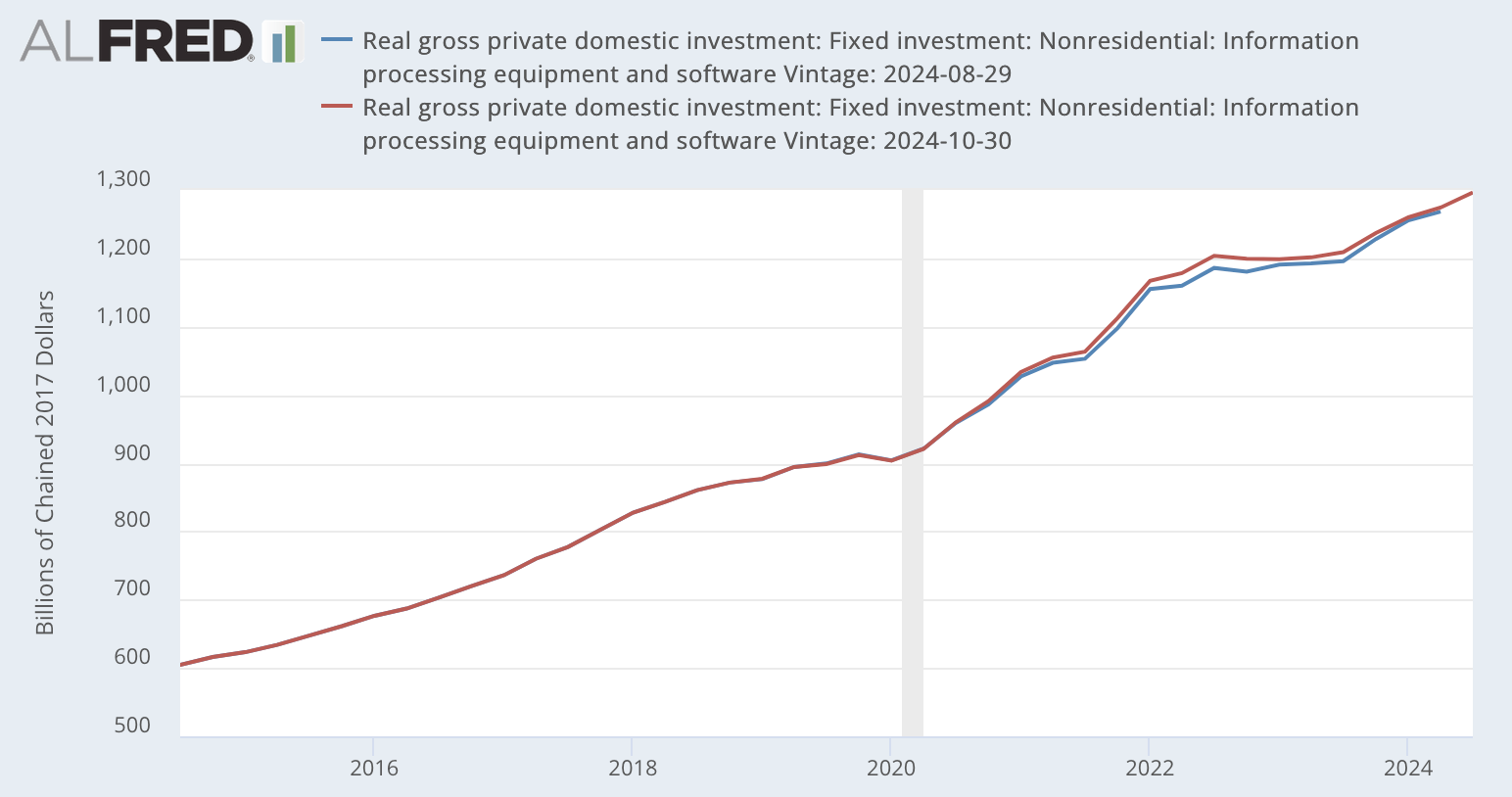

September's GDP revisions and today's data suggest we're in the midst of a hand-off from factory expansion to investments in industrial equipment (presumably to fill some of those factories). Industrial equipment expenditures will be worth watching in the coming quarters.

That said, not all of the upward revisions to investment are necessarily tied to explicit public investment efforts.

Research and development investments have been impressive through most of the post-pandemic period and some of the recent slowing may be attributable to the roll-off of certain TCJA provisions. Specifically, R&D expenses were eligible for immediate deduction but are now subject to 5-year amortization.

Finally, while many are eager to attribute strong productivity outcomes to artificial intelligence, we would recommend caution. We are only at the early phases of the capex-buildout (data centers, tech hardware, software). We don't doubt that it can have a profound effect on investment and total factor productivity in the future, but it likely does not explain the past 4-5 years of outperformance all that well.

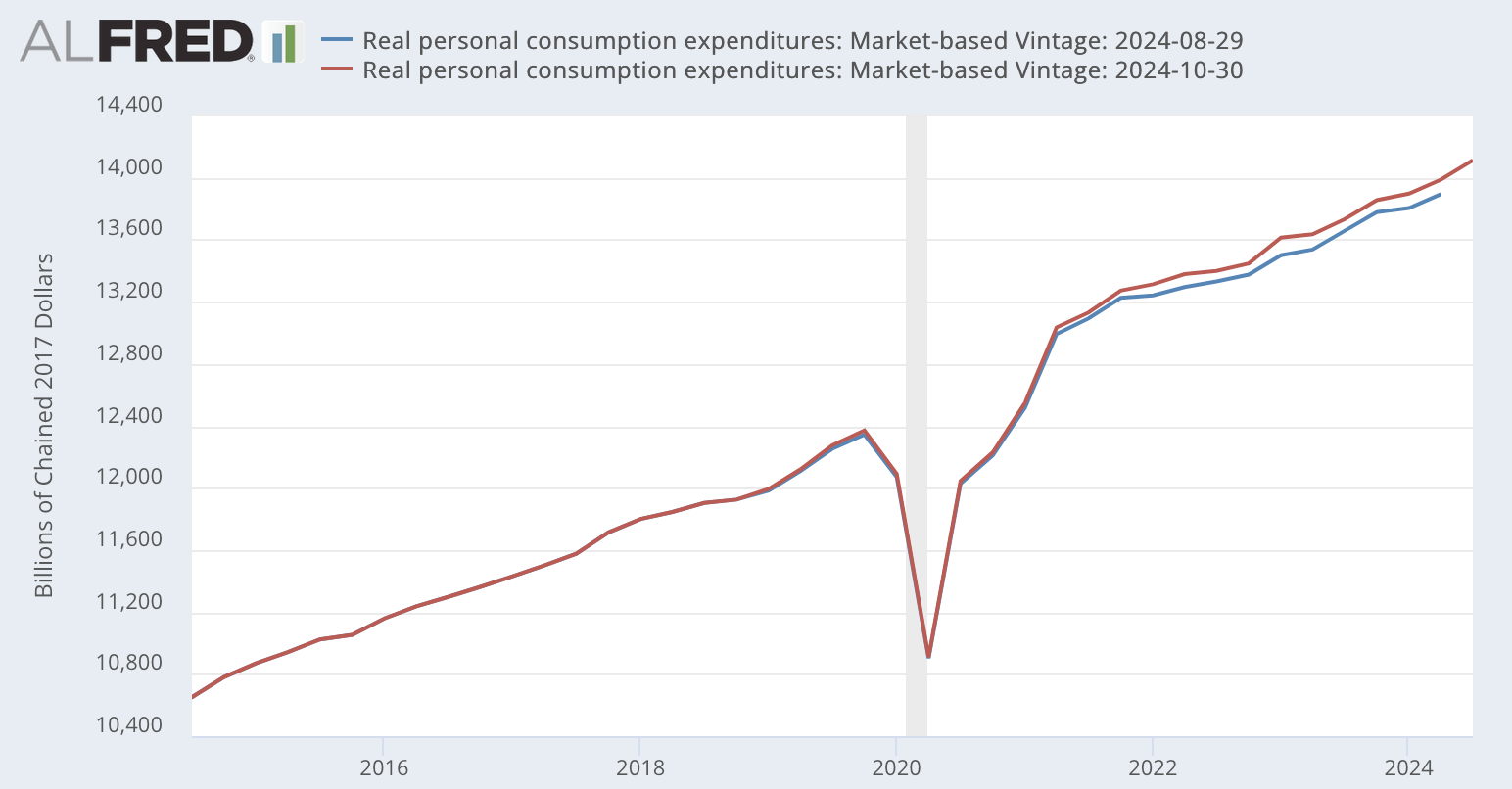

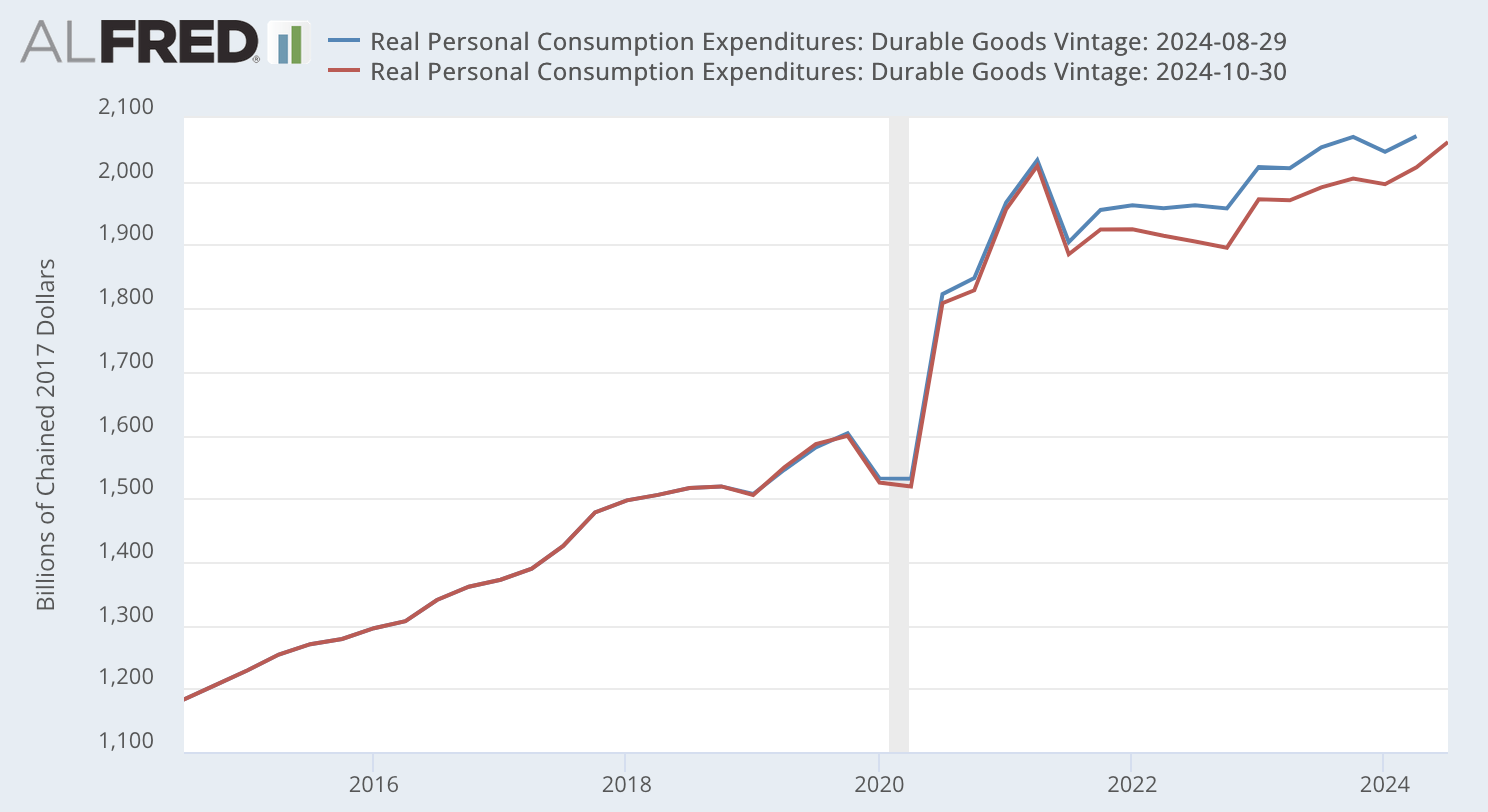

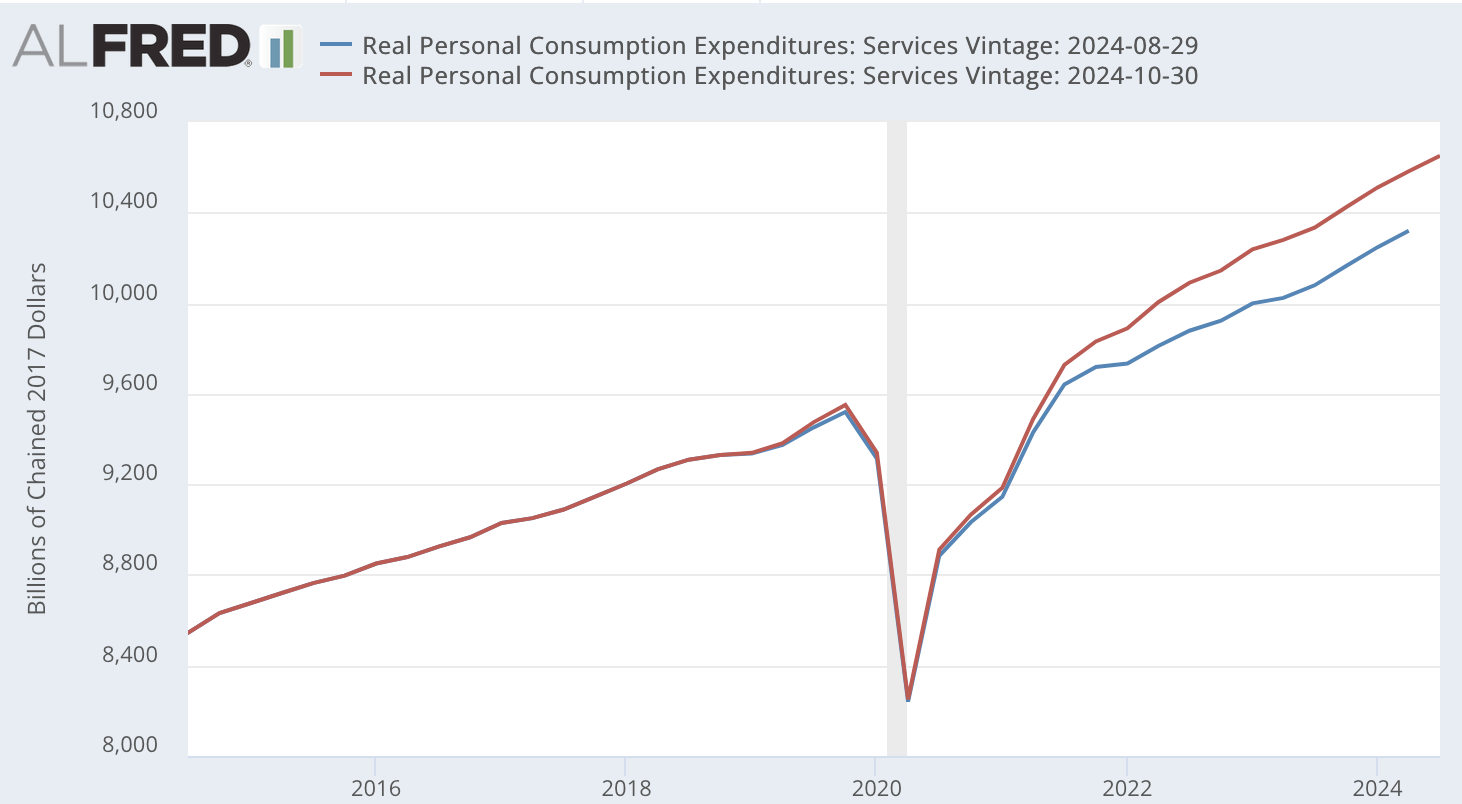

Above-Trend Real Consumption Reflects Both Supply Chain Healing and Service Sector Productivity

While private fixed investment has largely held on the same pre-pandemic trend, real output has outperformed alongside above-trend real consumption.

Even as inflation has substantially subsided (albeit still work to get back to the 2% inflation target), the levels of real consumption have likely stayed elevated because many of the supply-side factors pushing up goods and goods-adjacent services inflation (and pushing down on output growth) have begun to reverse.

At the same time, the latest revisions to the consumption data also suggest that consumer services output is running at least at the pre-pandemic trend, if not marginally better.

A Productivity Boom...If You Can Keep It

We will warn up front that while the productivity outcomes are highly encouraging, they are liable to hit bumps in the coming 1-2 quarters. One-off effects are likely to push down on real output in the short run, relative to employment. Among the dynamics at play include (1) hurricane effects on consumption, (2) election effects on campaign spending (which also count in consumption), and (3) the effects of the ongoing Boeing strike on aircraft output. These should unwind subsequently but we likely have yet to see even their initial impact on the productivity data.

One-offs aside, it's worth taking seriously that "trend productivity" of the past need not be—and typically is not—indicative of future trends in productivity growth. Potential growth involves dynamic properties.

Policy has a vital role to play in maintaining full employment conditions, creating a favorable environment for fixed investment, and addressing inflationary dynamics and risks. Among the more pressing dynamics that is not a pure one-off and substantially adjacent to policymaking: housing. Residential fixed investment is looking especially weak due to locally tight financial conditions and more conventionally "supply-side" constraints. Addressing these issues will be critical to unlocking additional productive output and mitigating its inflationary burden for households.

Warnings and caveats aside, the past few years make clear that so long as the foundations of full employment and a favorable investment environment remain intact, the outlook for US productivity growth should continue to look bright.