After the June FOMC meeting, we argued that the Fed should seriously consider the prospect of a July rate cut if the preceding jobs data, which we received on Friday, and the inflation data, which we’ll see later this week, were soft. So far, that case remains intact: the June labor market data confirmed enough of a labor market slowdown that the labor market has softened appreciably, although not alarmingly. As the July meeting approaches and Powell testifies in front of Congress at this week’s Humphrey Hawkins hearings, Powell and the rest of the Committee should keep the door open to a cut at the July meeting.

The big headline from Friday’s labor market data was that the unemployment rate rose once again, to 4.1%. The unemployment rate is now approaching the oft-cited 0.5% threshold of the Sahm Recession Indicator.

Is this a sign that the labor market is on the precipice of entering a recession? Not in and of itself. Historically speaking, increases in the unemployment rate that large are also associated with falls in employment. By contrast, prime-age employment remained above pre-pandemic levels in June. A prime-age employment analog of the Sahm unemployment indicator (the difference of the 3-month moving average prime-age employment rate from its peak in the past year) is currently just 0.06.

In other words, the increase in unemployment is a result of employment remaining steady while labor force participation has increased. As Guy Berger notes, the increase in the number of unemployed is nearly entirely accounted for by new entrants and reentrants to the labor force. While that’s certainly a better picture of the labor market than one where unemployment is rising due to layoffs, that doesn’t mean that the rise in unemployment is nothing to worry about.

Even in the absence of layoffs, a slowdown in hiring is nothing to underestimate. Hiring is currently at a pace just sufficient enough to replace separated workers and maintain the current level of employment, but not rapid enough to absorb new entrants. But if hiring falls further, we could see employment rates start to slip.

The question is, how much is left before further softening in the labor market translates to outright job losses? Fed officials repeatedly acknowledge that the labor market is “moving into better balance.” Whether you measure that balance through quit rates, wage growth, or the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio, it looks like we are at or getting close to that balance. For example, average hourly earnings growth is now south of 4%, and the Indeed Posted Wage Index is at 3.1%. The most prominent argument that the labor market might be overheating was the eye-popping rate of payroll employment in the establishment survey, but there is growing evidence that this is reflective of higher rates of immigration rather than reaccelerating labor demand.

“If you’re applying a monetary policy rule, which said, I’m going to keep slamming on the brakes until wages come down to a growth rate that is compatible with 2 percent inflation, you will almost certainly overshoot the target.”

Austan Goolsbee, interview with Kyla Scanlon (7/3/24)

Just as nearly every Fed official has said they should not and will not wait until inflation is at 2% to cut, they should also not wait until the labor market is in perfect balance between supply and demand. As the labor market softens, the appropriate policy response is to begin lifting restriction, not holding the federal funds rate at this level even while inflation has fallen so much.

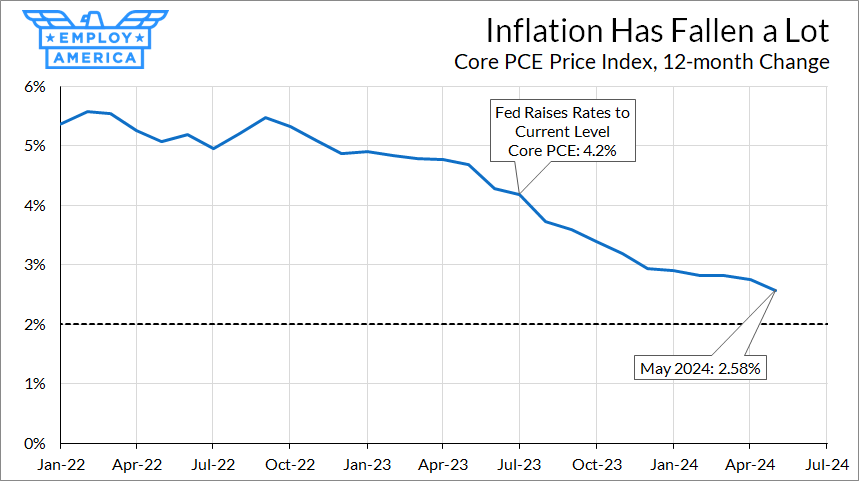

On the other side of their mandate, core PCE inflation has fallen from above 5% to just below 2.6%. While this is by no means the same as 2% and progress on year-on-year readings may be more difficult in the coming months as the low inflation readings in late 2023 fall off, there is no denying the progress that’s been made. Furthermore, there is substantial reason for optimism on inflation with rent and OER dynamics.

If Powell's testimony in front of the Senate on Tuesday morning is any indication, the Fed is starting to recognize these risks to the labor market more:

He's not the only one voicing growing concern over unemployment risks. On the dovish side of the Committee, Daly and Goolsbee have delivered similar remarks in recent weeks.

Now that they recognize that the risks have shifted, will the adjust policy appropriately? The case for cutting soon is simple: unemployment has risen and inflation has fallen; policy should adjust accordingly. At this point, the question is no longer “What’s the rush”, but “Why are we still here?”

Note: This piece has been updated to include the video clip from Powell's Tuesday, July 9th in front of the Senate.