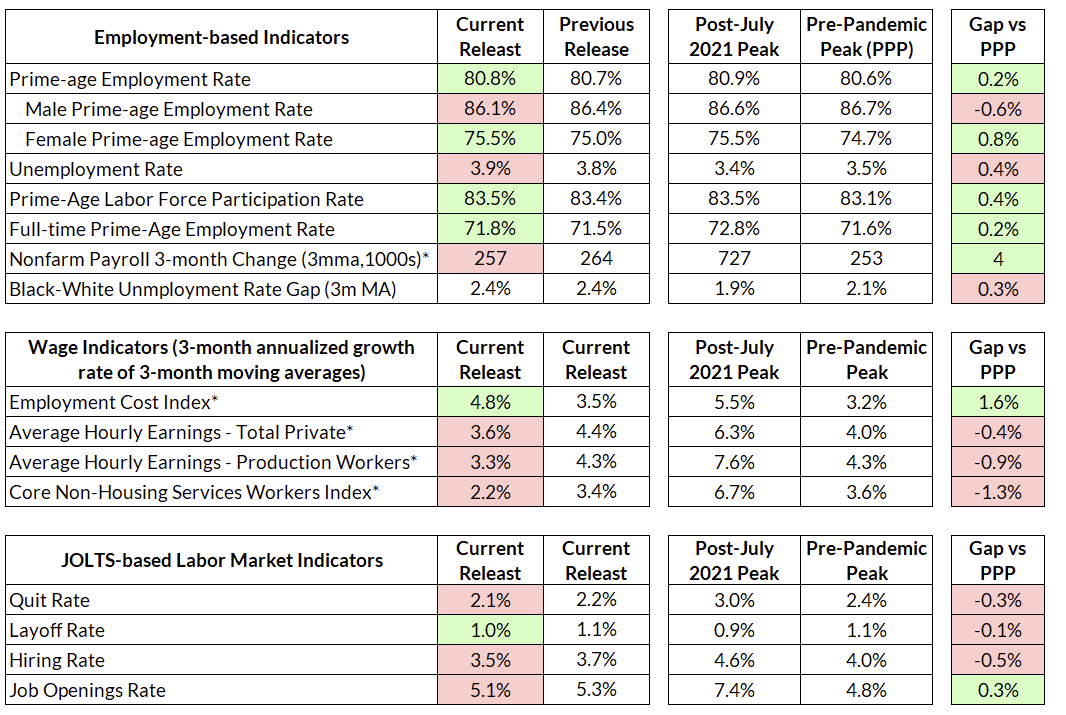

The labor market added 175,000 jobs in April, with minor revisions to February and March. The headline unemployment rate increased slightly by 0.1% to 3.9%. The prime-age employment rate increased by 0.1% to 80.8%, just off its post-2020 high. Full-time employment rebounded somewhat while part-time employment fell, partially undoing some of the divergence in these two measures over the past nine months. Average hourly earnings showed a very soft print, with both total and production workers coming in at a 2.4% annualized rate in April. Core non-housing services wages were especially weak. The JOLTS also showed softness, with both quits and hires falling.

April was a goldilocks month for the labor market and monetary policy. It’s a softer month than the hot prints in Q1, but not at all soft enough to raise concern that the labor market is breaking. 175,000 net job growth was a miss, but is still a respectable number. Wage growth, at least in April, is at an encouraging pace for the Fed. The data is consistent with those hoping for a soft landing—and soft landing cuts.

Labor Market Dashboard: April 2024

A Goldilocks Labor Market

Despite the “miss” on the jobs number, this is still a very strong labor market. Both prime-age employment rates and labor force participation rates climbed. Prime-age employment rates have been rising over the past four months, and now just 0.1pp off their peak of 80.9% last year.

While the payroll employment print came in under expectations, 175,000 net new jobs is not a bad pace at all. It’s perfectly consistent with a steady rate of 200-250k jobs a month, just above the pace of increase the labor market experienced in the few years before 2020.

We also saw progress on one potentially concerning front: full-time employment. Full-time employment, which rebounded to its pre-pandemic levels by June of 2023, subsequently fell and failed to recover. Meanwhile, part-time employment rose. This month saw a substantial rebound in the full-time employment rate.

Finally, the Fed will be encouraged by the continued deceleration in average hourly earnings this month. While wage growth in Q1 was fairly firm, especially in the employment cost index, average hourly earnings grew at a scant 2.4% annualized rate in April. Wages in core non-housing services are now growing at just above a 2% annualized rate on a 3-month basis.

Of course, this is just one month’s print and could revert or get revised away next month. But all of the signals from this month’s data should provide relief to Fed officials who might be worried that the labor market—and its effects on inflation—are reaccelerating. The deceleration narrative remains intact.

The Great Stay

If one were to just read the headlines citing payroll employment growth over the past few months, one might get the impression that the labor market was reaccelerating as payroll growth picked up. However, a closer look at hires and separations shows that the pickup in net employment growth isn’t due to stronger hiring. Both hiring and separations have been steadily falling over the past two-and-a-half years. The recent “reacceleration” in the payroll numbers in Q1 2024 appears to be driven mostly by a greater fall in separations, not a pickup in hires. That’s a stark difference from previous labor market accelerations, which were driven by a pickup in hires.

The decline in separations has almost entirely been driven by a fall in quits, with some improvement coming from decline in layoffs after a temporary pickup in white collar layoffs in late-2022 / early-2023.

The recent strength in payrolls growth was due to a continuation of what Guy Berger has termed “The Great Stay,” where people are simply leaving their jobs (either voluntarily or involuntarily) less often, while hiring remains steady. As I wrote two months ago, a large part of this simply reflects a decline in job churn that may lead to higher productivity as people settle into their new jobs.

A Quick Note on Response Rates and Revisions

The response rate on the establishment survey has been steadily falling over the past few years, prompting concerns that the initial report of the jobs numbers may not be trustworthy. At times in the past we’ve marginally shaded down the establishment survey when the response rate on the first collection was low, as have many other labor market watchers.

However, if one actually looks at the data there isn’t any obvious relationship between revisions to the payroll prints and initial response rates. Below, I plot the percentage difference between the initial payroll print and the final (third) payroll print against the percentage increase in the response rate between the initial collection rate and final (third) print.

There isn’t any obvious relationship between the size of revisions to the payroll numbers and the response rates. The correlation between the absolute value of the payroll revision (in percentage terms) and the increase in the response rate is a scant 0.05. The optimistic take here is that the establishment survey is large enough that even a low response rate is not fatal to the accuracy of the report—but the flip side of that is that even a high response rate does not necessarily mean one should gain confidence that the initial numbers will survive revisions.

Fed Outlook

The Fed’s next meeting in mid-June will have an additional round of labor market data, as well as a full month of inflation data and an additional CPI print the morning of the meeting. While this month’s data should give some relief to worries that the labor market is “reaccelerating,” the committee has plenty of time to collect more data before making more dovish gestures. If the labor market stays this cool and inflation cooperates, the Fed needs to start thinking about cutting sooner and faster.